This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Aix-en-Provence in 2025 has resembled the Holy Year in Rome. The difference is that pilgrims to Aix have come not for religious but for artistic indulgence. This small Provençal city has been celebrating, to the nth degree, its most famous son: Paul Cezanne (the city, like the artist himself, did not use an acute accent over the first “e” of his name). Art lovers have been processing to sites associated with Cezanne’s works in and around the city in veneration of this hugely significant post-Impressionist artist, rightly regarded by many as the father of Modernism.

Born in Aix in 1839, Cezanne lived, worked and died here. In adult life he divided his time between Paris, where he deposited his wife and son, and his hometown. In Paris and nearby Pontoise, he mixed with the greats, including Pissarro, Monet and Renoir. Of equal influence were the Old Masters in the Louvre, whom he studied fervently — with particular reverence afforded to Poussin’s landscapes and Rubens’ figures. Cezanne, arguably unsurpassed as a still-life painter, claimed that he would “astonish Paris with an apple”, but the metropolis was getting its artistic nutrition elsewhere, only really taking a tentative bite closer to his death, in 1906, before greedily tucking in directly afterwards.

Aix-en-Provence was his refuge — or as close to one as this troubled, insecure artist could manage. He made it all his studio: his home, his workshop and especially the surrounding countryside. (All, that is, except the city itself; he was not one to work amidst hustle and bustle.)

These settings provide the physical sites of Aix’s Cezanne 25 celebrations. Cezanne was fortunate in being born to a wealthy and generally indulgent father. The family’s summer home, Jas de Bouffan, then on the city’s outskirts, spacious in accommodation and land, was a nourishing environment in which the artist could develop. Currently undergoing major renovations of its many rooms, it was nonetheless temporarily opened for Cezanne 25 for the duration of the city’s major exhibition, before closing again. Here, two rooms are of particular interest.

The first is the grand salon, which his father generously conceded to his son as a mural proto-studio in which to experiment. Clever projections show the walls with various stages and paint-overs of Cezanne’s early efforts. They are pretty much uniformly awful, mostly comprising maladroit, unimaginative rehashes of classical themes that could hardly have inspired viewers’ confidence in the young Cezanne’s potential.

A little better is his side portrait of The Painter’s Father, Louis-Auguste Cezanne, (c. 1865; initially an oil painting on the salon’s plaster wall). The artist’s long-lasting problematic engagement with the human form is very much on display here; it is hard to ponder what his father really thought of his son’s gauche efforts at this stage. But it was a start. Perhaps Louis-Auguste concluded that the house’s interior décor would be improved by creating for his son a dedicated studio on the top floor. Its remarkably modern, large window looks like a much later extension, and it certainly disrupts the elegant lines of the 18th-century mansion.

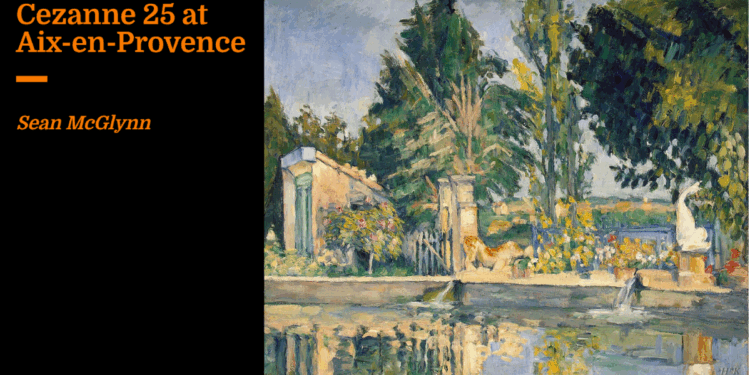

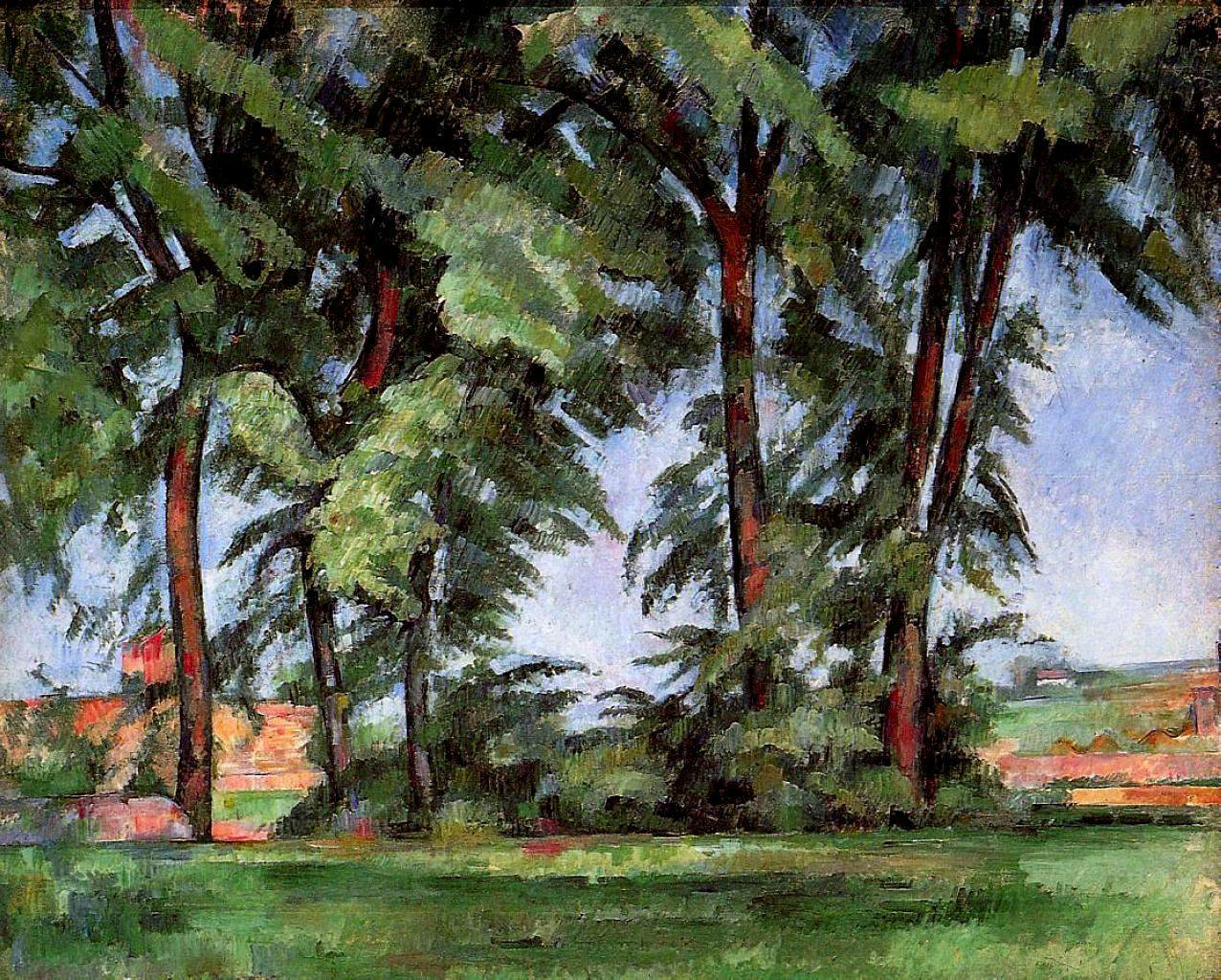

Over the years, the real source of inspiration at Jas de Bouffan came from its gardens and the house itself. Here, Cezanne created some true masterpieces, especially in his more assured, mature years: the angular beauty of The House in Aix (Jas de Bouffan) (1885-87); the vivid greens of Tall Trees at Jas de Bouffan (c.1883); the uplifting luminescence of The Pond at Jas de Bouffan [4] (c.1876), to name but a few.

As Jas de Bouffan shuts down for renovation, so Cezanne’s studio, Atelier des Lauves, has just reopened after its own lengthy closure. Having finally come into money on his father’s death in 1886, Cezanne had this new studio built 20 minutes outside of Aix on a hill with, at the time, clear views of Mont Sainte-Victoire; it was the only property he was to fully own. After it was completed in 1902, Cezanne would ascend from town in the cool of morning and, with a huge window drawing in the neutral northern light, here he would focus primarily on his masterful still lifes and his often bewildering, but always interesting, portraits.

The renovated studio is a museum-like piece with artefacts made famous in Cezanne’s paintings: the grey ginger jar, ugly plaster cupid, and the green olive pot, the last often substituting as a flower vase and always painted with striking vibrancy. In part two of Peter Handke’s shambolically solipsistic Slow Homecoming trilogy, the writer correctly identifies that these “belongings had become relics”.

With one of Cezanne’s last palettes in situ, the place resonates with immediacy. A large photo from his final year shows him emerging from the studio carrying a chair into the garden, adding to the poignancy of an artist who, at the end of his life, had finally earned the accolades of many peers and acolytes.

Another 15 minutes’ walk up to the brow of the hill brings you to Les Jardins des Peintres, from where Mont Sainte-Victoire can be seen dominating the lush countryside.

The most prominent of his motifs, Cezanne painted it obsessively, some 87 times, many works being masterpieces, not least Mont Sainte-Victoire [6] (1885-87), in which a large pine tree in the left foreground frames the landscape and the blueish-purple mass of the central mountain, whilst a linear viaduct angles off to the right. His landscapes depict human occupation and evidence of activity, but not people themselves — a welcome innovation in art.

Aix had still more for Cezanne’s canvases: just over an hour’s walk from town lies the granular slabs of Bibémus quarry where, in his later years, Cezanne spent long days out experimenting with geometric forms, earning the admiration of Cubists such as Picasso and Braque.

All these places were brought together in the impressive international Cezanne exhibition that ran at Aix’s Musée Granet from late June to October. Given that a director of the museum during Cezanne’s younger years vowed that none of Cezanne’s paintings would ever be shown in the museum (perhaps understandably, given some of the artist’s earliest efforts), this marks a posthumous triumph for Cezanne, especially as the exhibition, Cezanne au Jas de Bouffan, is rigorously focused on his time and work in Aix, where he was never fully appreciated in his lifetime.

Here, with more than 130 paintings and sketches, the full range of his work was on show, from clumsy juvenilia to visionary genius.

Portraits featured heavily, including the impressive Woman with Coffee Pot (c.1895), its vertical and horizontal arrangement prefiguring Cubism, and the freakish but weirdly engaging Seated Peasant (c. 1900-04), depicting monster-like claw hands in a weird distortion of perspective. Cezanne’s problematic figures were here to bemuse, as he attempts with varying degrees of success to transfer Ruben’s adipose nudes into the twentieth century, not least through his ongoing series of works, Bathers.

As wonderful as the local landscapes are, it was the disjointed, gravity-defying still lifes on tables that stole the show and marked the painter’s greatness. Still Life with a Plate of Cherries and Peaches (1885-87) is glorious enough, but the large-scale Kitchen Table (1888-90) encapsulates Cezanne at the height of his power and artistic visualisation, elevating the quotidian to the sublime. Cezanne was anchored in Aix-en-Provence, but it was always his vision that created his horizons.