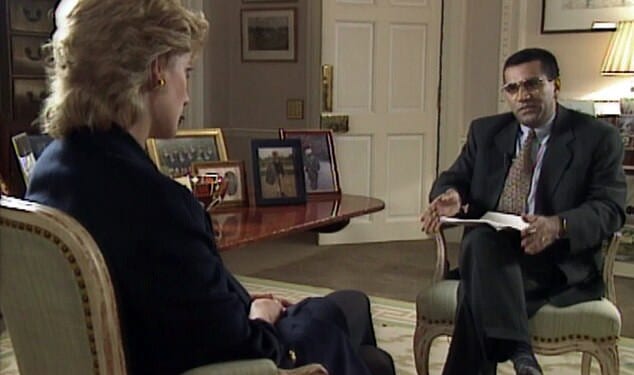

Billed simply and undramatically as ‘An interview with HRH The Princess of Wales‘, with no hint of what was to come, the programme would turn out to be the most controversial broadcast ever made by the BBC.

But it was not at all what the 23 million UK viewers who watched the encounter between Panorama reporter Martin Bashir and Diana that Monday night in November 1995 (and the 200 million around the world) might have expected.

Recorded a fortnight earlier, it was in reality not an interview but a performance – a double act, devised, rehearsed and delivered with a specific object in mind.

But what a performance! Unforgettable, even decades later. Diana’s eyes are wide, like a hunted fawn’s, as she declares: ‘There were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded.’

It is a good line, and brilliantly delivered. Diana, with a wholly unexpected fluency, flips back rehearsed, sound-bite answers to the questions ping-ponging her way. Like an A-lister on the chat-show circuit, she effortlessly trots out zingers: ‘I’d like to be a queen of people’s hearts. In people’s hearts.’

And they were not all soft questions. Bashir wanted to know if she’d had sex with her boyfriend, James Hewitt, during her marriage to Charles. ‘Were you unfaithful?’ he asked. ‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘I adored him.’ It was in the last five minutes of the 54-minute show that Diana delivered the lines intended for Buckingham Palace.

Did she expect to become queen? ‘No.’

Should Charles become king? ‘I don’t know whether he could adapt.’

Would it be your wish that Prince William succeed the Queen rather than the current Prince of Wales?

Martin Bashir’s interview with Diana was watched by an estimated 200 million people worldwide

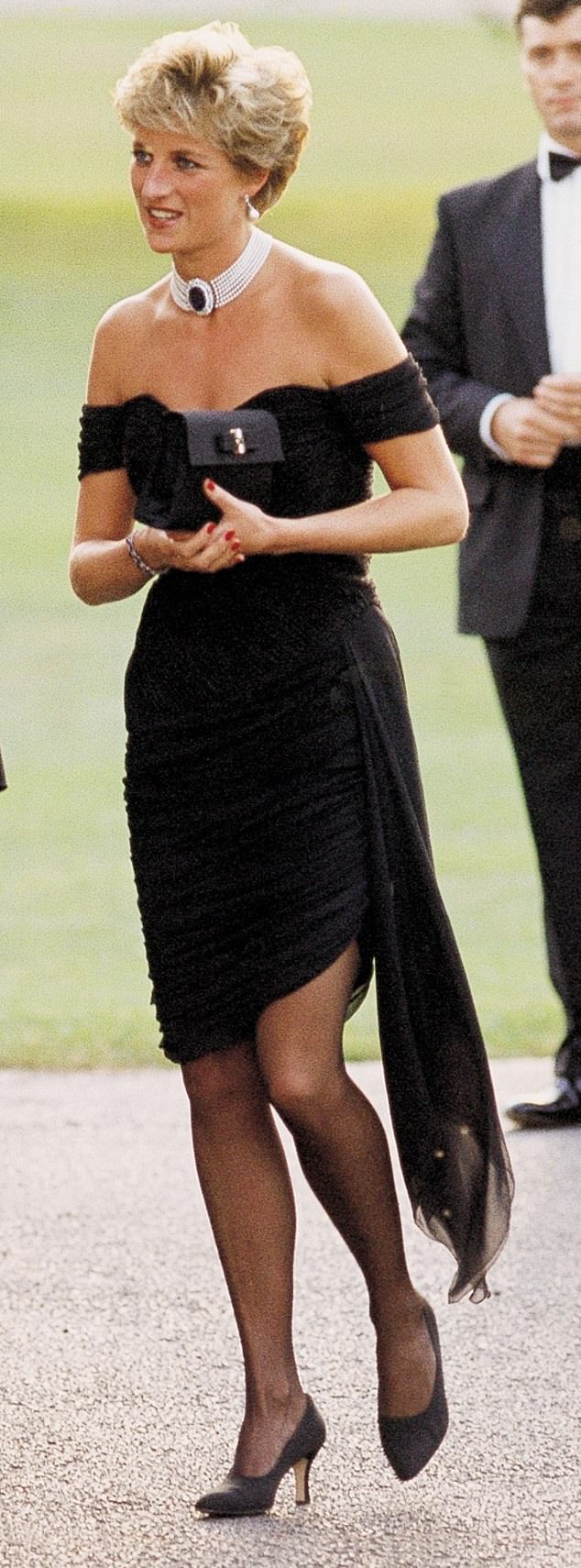

Diana’s eyes are wide, like a hunted fawn’s, as she declares: ‘There were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded’

‘My wish is that my husband finds peace of mind.’

She was predicting her own abdication, along with the dismissal of the next king, to be replaced by his son – with Charles presumably left to live out the rest of his life in quiet exile. King of Highgrove, Prince of Losers. This was extraordinary, unprecedented stuff. And the consequences were devastating.

That Panorama interview was 30 years ago but it still reverberates with her son, the Prince of Wales. What happened to his mother remains a matter of burning intensity for the heir to the throne who, as a 13-year-old schoolboy, watched her tell the world of sex with a lover, then trash his father, on television. His life thereafter was shaped by what Panorama did to his mother.

The news that Diana and Charles would divorce followed one month after the interview. And less than two years after that, Diana was dead, killed in a car crash as she was chased by the paparazzi through a Paris tunnel with her then lover Dodi Fayed – playboy son of former Harrods owner Mohamed Al-Fayed.

So the paparazzi can be blamed. But it’s not just them. William points at the BBC, and the cover-up it so shamefully instigated once it became apparent that Martin Bashir had lied and tricked his way into Diana’s confidence.

When a report into what amounted to one of the biggest scandals in BBC history was published in 2021, William declared: ‘It brings indescribable sadness to know that the BBC’s failures contributed significantly to my mother’s fear, paranoia and isolation that I remember from those final years with her.

‘If the BBC had properly investigated the complaints and concerns [about the programme] first raised in 1995, my mother would have known that she had been deceived. She was failed not just by a rogue reporter but by leaders at the BBC who looked the other way rather than asking the tough questions.’

He had put his finger on the real story here – the BBC’s failure to mitigate the harm done to Diana. After it was broadcast and the programme threatened to erupt into an enormous scandal, key people at the BBC had to make a crucial ethical choice: Do we cover things up, or do we come clean?

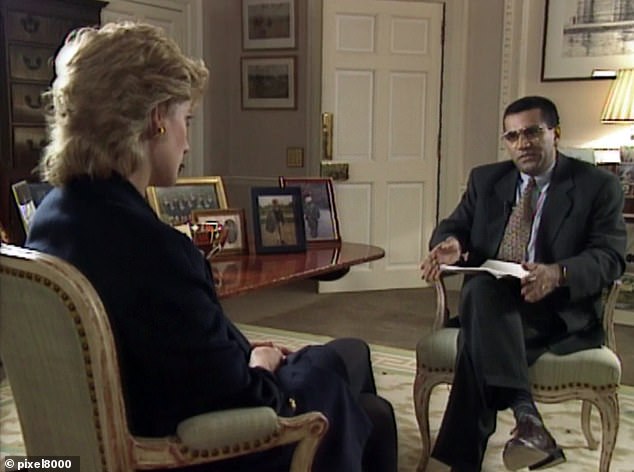

A 2021 inquiry found Martin Bashir guilty of deceit and breaching BBC editorial conduct when securing Diana for the interview

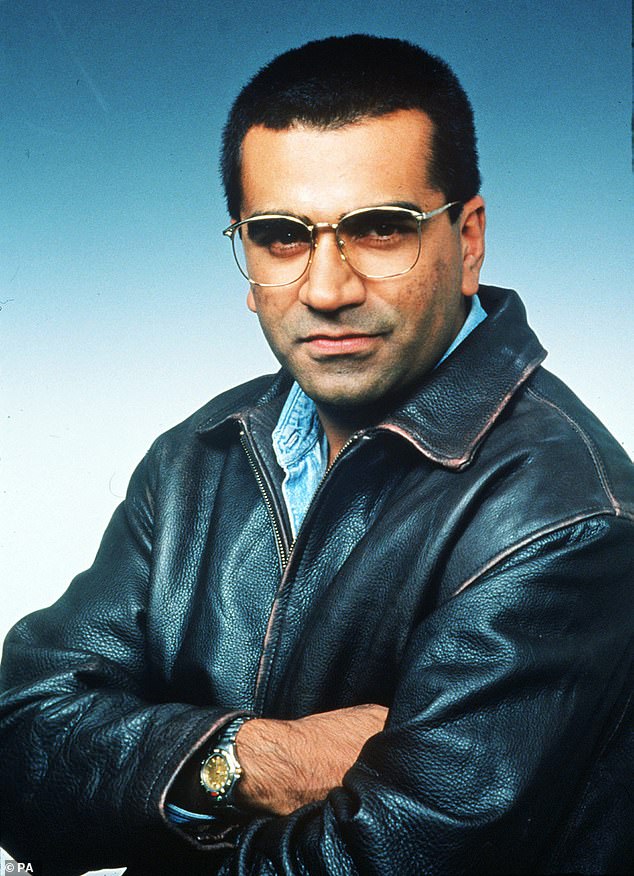

Diana wearing her famous ‘revenge’ dress following revelations about Charles’s infidelity

They could have stopped the runaway train that Bashir had set in motion. Instead they chose to put all the blame on him, claiming to have been taken in by him in the same way Diana was.

John Birt (now Lord Birt), the man who was running the BBC at the time, described Bashir as ‘a serial liar on an industrial scale’. In 100 years of BBC journalism he could not think of ‘anybody else who behaved in that kind of way.’ But had they all truly been taken in by him in such a comprehensive way? After all, these were top-flight media figures whose depth of experience and journalistic nous should surely have rung alarm bells over Bashir and his extraordinary coup in getting the Princess to talk.

Or had they, in search of a ratings boost, failed to act with due diligence when this virtually unknown member of staff – a colleague called him ‘barely a household name in his own household’ – presented them with the interview that everyone in the media, from Oprah Winfrey to David Frost, was desperate for and then, when it backfired, simply covered their own backs? Did they, in William’s words, look the other way?

My conclusion – after 20 years of investigating the Bashir affair, including going to court to obtain secret documents in the face of enormous opposition from the BBC – is that they most certainly did.

The most chilling aspect of the BBC cover-up in 1996 is that a line can certainly be drawn from Panorama to Paris. A judgment on how thick that line is, how straight, varies from person to person. But Diana’s alternative therapist, Simone Simmons, does not hold back.

She told me: ‘It’s unforgivable. To feed her a pack of lies, to make her an emotional wreck, which he deliberately did? Without Martin Bashir she would never have been in Paris with Dodi Fayed and she would still be alive.’

The BBC – perhaps the world’s most respected journalistic enterprise, which should be shouting loud for truth and honesty – instead worked furtively to prevent people uncovering its misdeeds. As William put it: ‘These failings not only let my mother down and my family down; they let the public down, too.’

What I think the BBC still does not appreciate is that this is a story which will not go away.

Charles himself was interviewed by Jonathan Dimbleby prior to Diana’s bombshell interview

That Panorama interview was 30 years ago but it still reverberates with the Prince of Wales

Its leaders today need to understand that the magnitude of what happened that winter night in 1995 has not diminished.

They must realise that, by ducking and diving, the BBC has put itself in an extraordinary position regarding the one person in the world whose concerns it is not just heartless to ignore, but foolish, too.

In the fullness of time it will be King William who issues the royal charter, the formal statute renewed every ten years under which the BBC operates. But the BBC now has an implacable antagonist in William. He has people taking steps to discover what truly happened inside the BBC, before and after the Panorama interview.

And the more the BBC acts suspiciously, the more William becomes convinced that there is something he is not being told. Those at the top of the BBC would do well to consider how powerful the motivation to discover the truth is for someone whose entire life has been shaped by these events.

It has been described to me as ‘an open wound which will not heal’ for William. There was a clue to this in 2022, when former royal nanny Tiggy Legge-Bourke was awarded substantial damages from the BBC for allegations by Bashir that she had an affair with the then Prince Charles and also had an abortion.

She commented afterwards about ‘the distress caused to the Royal Family. I know first-hand how much they were affected at the time, and how the programme and the false narrative it created have haunted the family in the years since.

‘Especially because, still today, so much about the making of the programme is yet to be adequately explained.’

That is what Tiggy believes, what William believes and, for what it is worth, what I believe. The question raised implicitly by Tiggy continues to cry out for an answer. What really happened and who is to blame? What had prompted the Princess to go so far out on a limb that there was no way back for her in the Royal Family?

Tiggy Legge-Bourke was awarded substantial damages from the BBC for allegations by Bashir that she had an affair with the then Prince Charles and also had an abortion

One key motive for her actions was that she wanted to take revenge on Charles.

Shortly before, he had taken part in a televised interview by the celebrated journalist Jonathan Dimbleby, then compiling the Prince’s authorised biography, for a documentary on his life.

The aim had been to portray him as a serious man, doing serious things – a broadsheet blast against tabloid sniping.

But, ahead of filming, Andrew Morton’s ground-breaking book detailing Diana’s unhappiness, was released. This was followed by the outing of Camilla Parker Bowles as Charles’s lover, and then Charles and Diana’s formal separation.

For its documentary, ITV now wanted more than monologues about racial harmony, youth clubs and organic fertiliser. What about the sex?

Filming had been concluded but the broadcaster sent Dimbleby back to interview Charles again and pose the crucial question. At first Charles declined to answer. But ITV insisted.

Did the Prince seriously believe he could be allowed more than two hours in the nation’s ear without telling it the single thing it was yearning to hear? He was persuaded that if he just came clean, speculation in the tabloids about him and Camilla would stop.

And so, despite his reservations, on camera he admitted to being unfaithful to his wife.

It was a terrible misjudgment. Diana reacted with icy rage, determined to have her revenge. She felt Charles’s decision to ignore his instinct for discretion and admit adultery gave her permission to make her own confessions.

But the most important trigger of all, when it came to the Princess’s fatal decision to go public with the secrets of her private life and her sex life, was Bashir and the lies he had fed her in order to secure the interview.

When she first met him, she was already convinced that ‘dark forces’ were conspiring against her, her phones were being tapped, her car followed and her favourite police bodyguard murdered in a faked road accident.

She was sure her own death was being plotted. She was ripe for anyone wishing to pour poison into her ear.

Bashir – ambitious, ruthless, unprincipled – saw his opportunity; a chance for fame and fortune.

He manufactured a meeting with her brother, Charles Spencer, approaching him out of the blue with suggestions that Diana’s closest adviser, her private secretary Patrick Jephson – the one person with the quiet voice of reason who could deal with her mercurial nature – was in the pay of those ‘dark forces’ and was spying on her.

The bait scattered on the water at Althorp, the Spencers’ family home, was snapped up right away by Diana in Kensington Palace when her brother passed on the message. She was hooked – not least because this was coming from someone in the BBC, the most trusted, the most august, the most boring-in-a-good-way news outfit in the world. It must be true.

They met and Bashir – a sober-suited fellow with gold-rimmed glasses, a man from not just the BBC but from Panorama, its A-team when it came to digging out state secrets – spilled his version of what was going on, laying out a whole cast of characters actively spying on her and plotting against her.

Three phone lines tapped at Kensington Palace. Bugs in her car. Her husband in love with Tiggy the nanny, who’d had an abortion – with Charles said to be the father. Camilla about to be dumped and even killed. Jephson on the take. Daily Mail reporter Richard Kay, whom Diana liked the most of all the royal press pack, untrustworthy and in cahoots with Charles’s people.

It was, as Kay observed, all an attempt to appeal to her paranoia, and also to insert a wedge between her and her friends, her close circle – to isolate her from those who would steer her away from Bashir and his concocted stories.

There was more. Bashir alleged Prince Edward had AIDS and that the Queen was ill with a dicky heart. And that the 13-year-old Prince William wore a special watch, a present from his father, that contained a device to record what his mother was saying.

Charles Spencer, who was also at the meeting and took notes, was alarmed. A journalist himself for around a decade – longer than Bashir in fact – Spencer ‘felt [he] was listening to a man who was not telling the truth. He was overexcited, but also shifty’.

Once Bashir had gone, he said to his sister, ‘I think the bloke’s full of c**p’. He thought that was the end of the matter.

He said later: ‘I didn’t know if he was a liar or a fantasist, but I knew he was bad news, and that was the end of him for me.’ Spencer never saw or spoke to Bashir again.

But Diana – who was no fool, it has to be said – had been watching a different movie that afternoon. For two hours she listened intently to one extraordinary revelation after another.

She was elated – delighted to know, for definite, that she was indeed surrounded by spies and traitors. That there was a whole tribe of people who wished her harm and had fiendish electronic devices, including a secret watch, that could help their wishes come true. Thus far there had only been suspicions. Now she had confirmation. She wasn’t crazy after all.

Simone Simmons, Diana’s New Age therapist, recalled how, after meeting Bashir, Diana was ‘terribly excited. She was floating on a cloud that you couldn’t get her down from’.

Of course, the whole thing was bonkers. The woman set to become the Queen had been persuaded by a man from the BBC that her husband was plotting to murder her. Indeed, not just her but his ex-lover, too – so that he could marry a young servant.

But she was convinced by what he had told her, and she acted quickly. Just 47 days passed between September 19, when she met Bashir for the first time, and November 5, when the interview was recorded and she came out fighting on camera.

The reaction to the programme that night was sensational, as if a thermonuclear bomb had gone off. Next morning’s newspapers sold in their millions.

Bashir received bubbling praise from an ecstatic Diana in a note: ‘Dearest Martin, There are no words adequate to express how I now feel having had my wings returned to me.’ She signed off, ‘Lots of love from Diana.’

There was more love for Bashir from Tony Hall, the BBC head of news and current affairs (now Lord Hall). ‘Dear Martin, You should be very proud of your scoop. It was the interview of the decade – if not of our generation. But equally importantly, you handled it with skill, sensitivity and excellent judgment.

‘There were many pitfalls awaiting us – you avoided them all. I also think you have carried yourself during this whole episode in absolutely the appropriate fashion. Thank you, Tony.’

Bashir was the BBC’s hero.

In other quarters, though, there were serious doubts right from the start. At Althorp, Charles Spencer sat down with his mother to watch Panorama, not knowing what was to come.

He had assumed Diana had heeded his warning about Bashir but, as he watched, it became clear that something had happened to her.

He told me: ‘It was rather like a Spanish bullfight where they prod the bull to give it extra pep.

‘She thought all sorts of bad things about Prince Charles that weren’t true – that he was having an affair with the nanny. But she had been told them. What came out of Diana’s mouth during that interview was the result of the lies she had been fed.’

Paul Burrell, Diana’s butler, was also suspicious. Though not there when the recording was made, he was adamant that it involved Bashir delivering prompts for soundbites.

‘It had been rehearsed,’ he said. ‘The Princess later told me she had to get it perfect. She knew exactly what the questions would be and how to answer them. She was coached by Martin through the minefield of the interview.’

Jephson watched on a sofa with one of Diana’s ladies-in-waiting as his reputation was publicly trashed. ‘Groans, exasperated laughter and terse exclamations of horror rose like nausea to our lips. Finally we watched in silence until we could stand it no more.

‘We switched off the TV and the ghostly face with the smudged, dark eyes faded from the screen. I emerged wearily from behind the sofa where I had taken refuge. “That’s it,” I said.’

The day after, an excited, pleased-with-herself Diana turned up for a session with her therapist, Simone Simmons, only to have cold water poured on her.

‘You made a real prat out of yourself,’ Simmons told her. ‘What about the boys there at boarding school? What do you think their friends are going to say now, seeing that you’ve publicly admitted to having an affair with a man other than their father?’

It wasn’t what Diana wanted to hear. If Prince Charles could go on television to make his case, as he had with Dimbleby, she pleaded, then why shouldn’t she?

Simmons said: ‘The whole world already knew about Charles and Camilla, but they didn’t know about you.’

Diana began to regret what she had done and, at one point, said she wanted to kill herself. Simmons told her: ‘No, you’re not going to do that. What you’re going to do is apologise to the boys and to everybody that’s involved.’

There is a story that she had gone to Eton the day before the broadcast. From their hiding place, two paparazzi photographers saw her trying to explain to William something which it seemed he just couldn’t grasp.

She was pleading with him but he was visibly upset. After a few more moments he walked away, making no attempt to kiss her or say goodbye.

He is said to have watched the interview alone in his room and was in tears by the end. And who can blame him? His family’s woes, his parents’ infidelities, had been aired to the entire world, privacy thrown to the wind.

Every word that his mother had uttered in that broadcast, every gesture and body movement, had been analysed by journalists and commentators.

Those journalists, though, were beginning to question what had gone on. Who exactly was this guy Bashir? And just what had he done to secure this amazing scoop? Slowly the whole dodgy business began to unravel.

In the rest of this series, I will track that unravelling and the cover-up by BBC bosses. Early on in the aftermath, when the BBC might have come clean and revealed to Diana that the interview had been gained through deception, it did not do so.

In the meantime, there were three long-term consequences of Diana’s interview to consider.

First, the Queen told her to get on with divorcing Charles. The only comment Her Majesty made about the interview outside the confines of the royal household was to tell theatre director Sir Richard Eyre, a member of the BBC Board of Governors, at lunch: ‘Frightful thing that my daughter-in-law did. Frightful thing to do.’

The second consequence was that, by going public in this way, Diana had exposed herself. Whatever benefits Bashir had promised Panorama would bring her, it is unlikely that he pointed out that, for the rest of her life, she would become fair game from the paparazzi’s perspective.

As one photographer put it: ‘If Diana was prepared to bare her soul on television, she would now have to accept she had given up her private life for ever. She could hardly complain if the Press wanted photographs.

‘After all, she was the one who had put herself firmly back on the front pages.’

This would become horribly relevant when, nearly two years later, she was chased into that road tunnel in Paris and died.

The third consequence was that Diana’s life was thrown completely off course.

Simmons told me: ‘I hold Bashir fully responsible for Diana’s death. Not partly responsible. Fully responsible. If it wasn’t for him, she would still be alive.’

For Charles Spencer, there’s also a link between the hoaxing of his sister and her death in Paris. As we sat in the library at Althorp, I said to him: ‘Let us imagine that the BBC had explained the situation to Diana as soon as they knew that Bashir was both a forger and a liar.’

In those circumstances, he said, ‘I think Diana would have restored her confidence in the right people around her, particularly Patrick Jephson.

‘But by destroying Diana’s trust in him and the team of highly trained professionals around her, the interview’s direct result was to leave her exposed to [Mohamed] Al-Fayed’s Mickey Mouse outfit of protection and drivers at a time when she needed proper safety. The consequences were lethal.’

I put the same scenario to Jephson. He told me: ‘The line from the Panorama interview leads pretty much straight to the night in Paris, where Princess Diana was in the hands of people who were unable properly to look after her.

‘The way Diana met her death was a result of [her] being separated from the protection of the royal machine. And a large part of that separation can be traced to the Panorama interview.’

That disaster might also have been avoided if the BBC had come clean when, six months after the interview was broadcast, it knew for sure the truth behind Bashir’s great coup.

Instead, it left Diana in the dark about the astonishing depth of his duplicity.

Had the scandal emerged when it should have – with the BBC explaining to Diana that Bashir was a lying fantasist, that he did not have a secret source within MI5, that Prince Charles was not planning murder, and nor would he marry the nanny Tiggy Legge-Bourke – it would have been a media sensation, but a temporary one.

Heads would have rolled at the BBC, but I think Diana would have survived the initial embarrassment of having been duped.

In circumstances where, so plainly, she had been led up the garden path by the one organisation in the country we are all brought up to trust, there would have been sympathy for her, as the victim.

Instead it was a very different set of circumstances that rolled out, ending in a tragedy that shocked the world even more than the interview had.

The image has been fixed over the past 28 years that, certainly in her final horrific moments, Diana was done to death by the media, as the drunken driver of the Mercedes was made deadlier still by the pack of manic pursuers.

It is not hard to hate the freelance paparazzi who chased Diana for the huge sums of money that the right photo would bring.

But it is now clear that Diana’s fate was not solely determined by the paparazzi, the scum. The august BBC was deeply involved, too.

Adapted from Dianarama by Andy Webb (Michael Joseph, £22), to be published November 20. © Andy Webb 2025. To order a copy for £19.80 (offer valid to 22/11/2025; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Diana claimed the film crew were hi-fi salesmen

Diana delighted in working out a plan to film the interview under a cloak of secrecy. A Sunday would make it much easier, she told Bashir; she also gave her butler, Paul Burrell, a day off, telling him to go home and play with his children. Diana insisted the BBC crew must total no more than three, rather than the six that would have been normal for such a job, and that they must declare themselves to the police at the Kensington Palace security barrier as salesmen coming to demonstrate a new hi-fi music system.

On November 5 – Bonfire Night – they duly passed the police post without a hitch, parked in the courtyard and knocked on the door of Apartment 8/9. Diana answered. ‘Do come in. Call me Diana.’ They walked up the stairs to the living quarters where the cameraman, Tony Poole, chose what was called ‘the boys’ sitting room’ for the interview. Nice fireplace. Curtains thick enough to stifle the crack and whistle and boom of fireworks outside.

The crew hauled over a table and arranged on it a few of Diana’s framed photographs (left), all precisely aligned so as not to throw back a reflection from the lights looming overhead. The interview would need two cameras: one looking at Diana, the other at Bashir to capture his questions and reactions.

What with the secrecy and the minimal crew, there was a delicious frisson of need-to-know that would result in the intimacy of the footage. For Diana there was no dresser, no stylist, no make-up lady. Those thin, dark rings around her eyes were all her own. What we see for most of the 54 minutes is Diana’s face, gliding a little closer one moment, pulling wider the next. To her right was a fireplace surround and a dark pool of nothingness; to her left a table lamp – a hopeful light.

Filming began at 9pm and finished at midnight, with nine tapes filled.

When it was all over, Diana waved off the crew and they left the Palace. Police couldn’t help noticing that those hi-fi blokes had been there for five-and-a-half hours.