This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

“The past,” observed L.P. Hartley, “is a foreign country. They do things differently there.” Never was a truer word written. We did things differently. Our streets were uncluttered save for red telephone boxes and parking meters, our BBC was universally respected and believed, and our policemen appeared kindly and approachable, unlike today’s Daesh-dressed robocops.

That is not to say that our forebears got everything right, or that all in their garden was rosy-tinted half a century ago. Stop/Go economics, industrial complacency, workplace strife — all beneath the penumbra of our withdrawal as a world power, combined to cast a pall over life beyond the bubble of swinging London. For every engaging and gregarious Georgy Girl, there was many a Poor Cow.

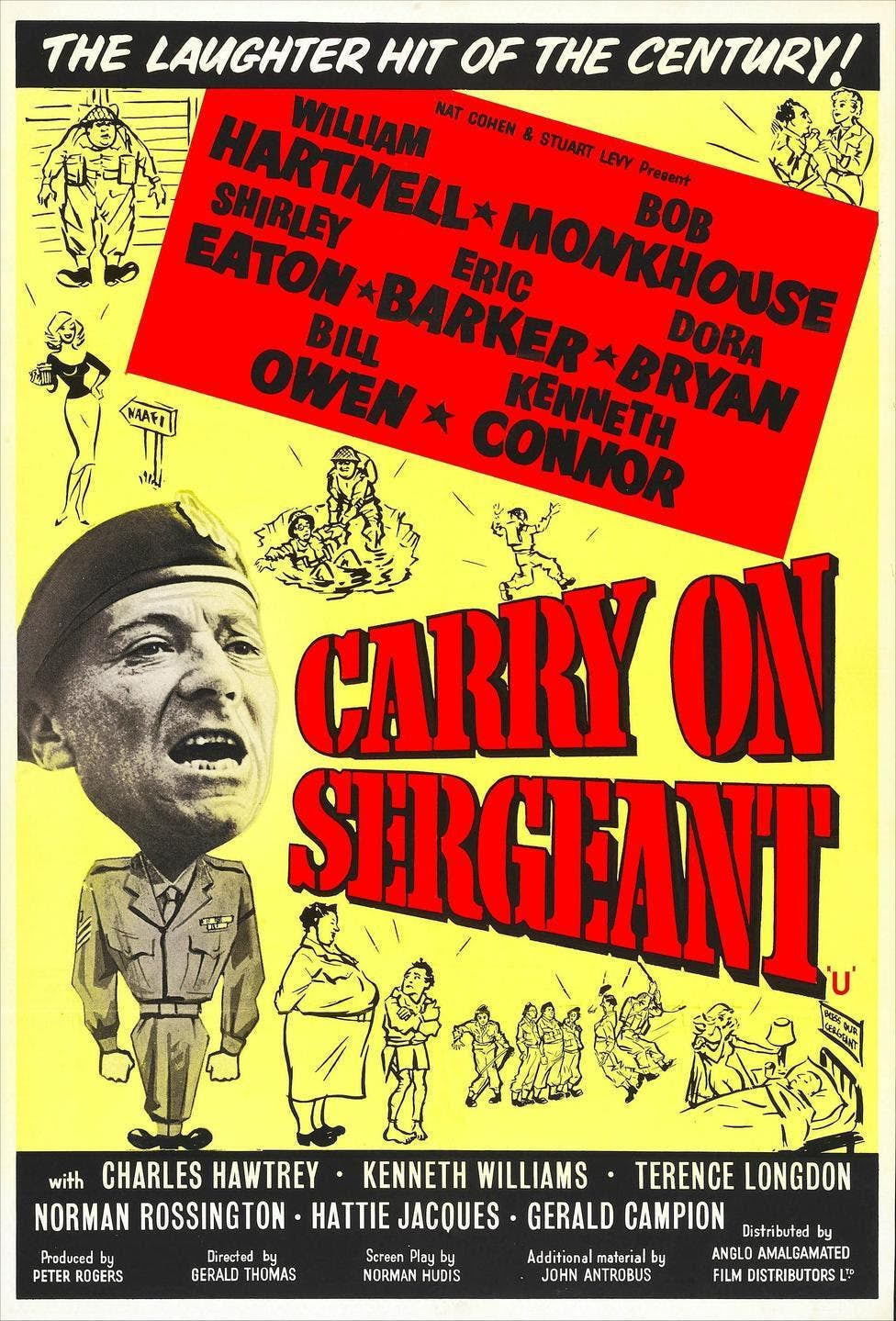

To escape the drudgery of late-1950s kitchen sink drama, Peter Rogers created the Carry On franchise and for over 20 years made it an almost annual festival of British silliness, sauciness and sentiment. The series (and only the Bond franchise has lasted longer or been more successful) was bookended by two similarly unfunny films: Carry on Sergeant in 1958 and Carry On Columbus in 1992.

Whilst Columbus bombed at the box office, effectively ending the run, Sergeant was tremendously successful. That speaks volumes about the extent to which British society changed and how the past became so foreign so quickly.

Back when it began, the British people (and we still called ourselves British people and not YooKay nationals as we have allowed ourselves to be restyled) were still essentially a Happy Breed: optimistic, sentimental but sufficiently self-confident to laugh at ourselves as readily as we laughed at everyone else. This was John of Gaunt’s cheerful “little world” presented for inspection through the Carry On cameraman’s lens.

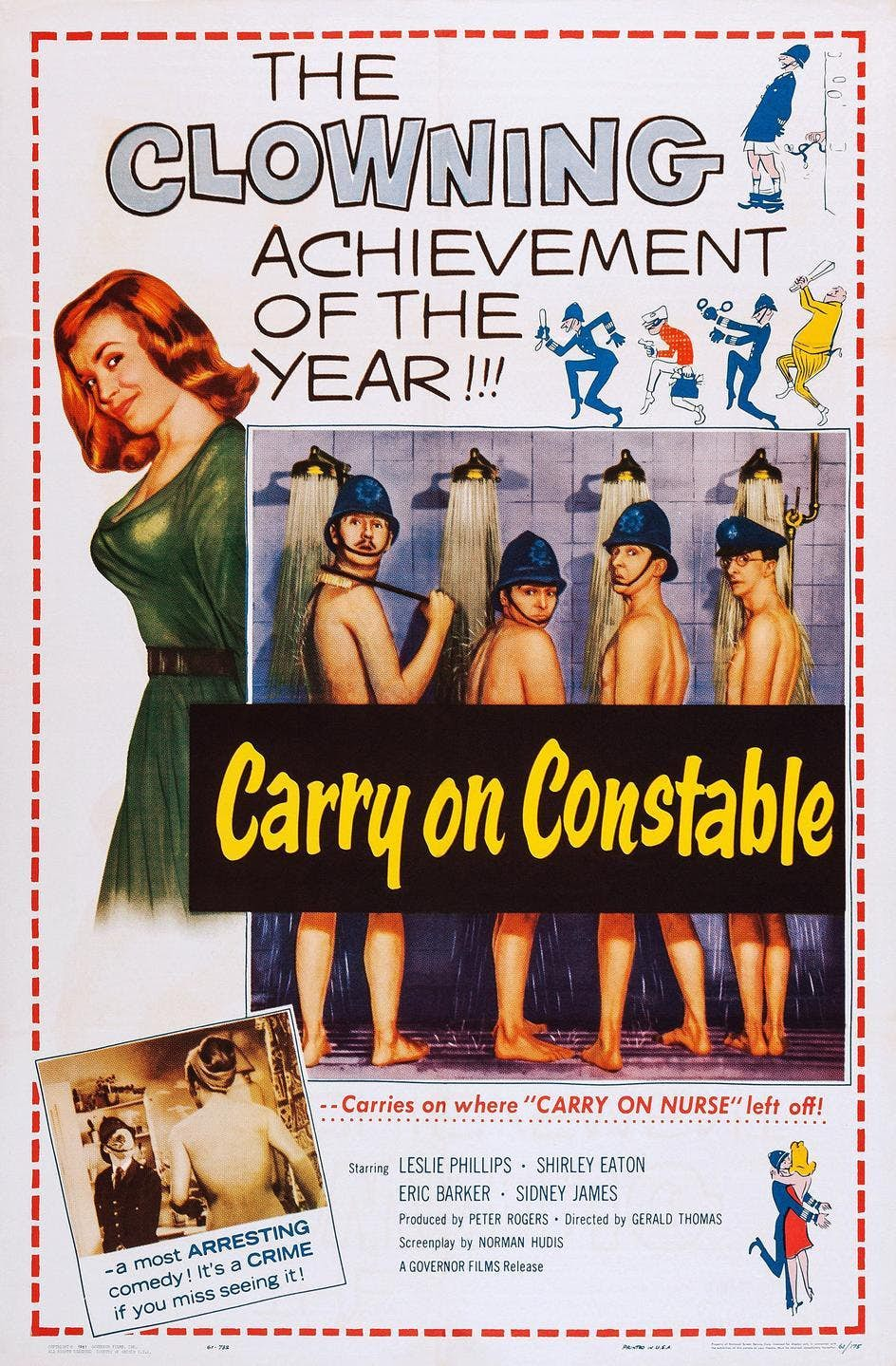

It took a while for the ensemble to assemble. Sid James, the star most identified with the series, did not arrive until Carry On number four (Constable). Barbara Windsor arrived in number nine (Spying), and Bernard Bresslaw pitched up in number 11 (Cowboy).

Not all the original cast stayed the course. Ted Ray and Leslie Phillips both left in pursuit of other projects whilst Charles Hawtrey was eventually dropped when his pursuit of the bottle made him unmanageable on set. But once they hit their stride in around 1964, there was no stopping the gang.

Institutions such as the monarchy, armed forces and trades unions, preoccupations with class, caravan holidays and “crumpet”, traditional stereotypes of hen-pecked husbands, petty officials and suspect foreigners were all sent up (never mocked) with merciless egalitarianism.

No one was above being lampooned, and no one was beneath it. The Carry On team pricked pomposity without fear or favour and without worrying, as many would today, what a self-defined “community” might say. Back then, Trigger was the name of Roy Rogers’s horse, not the mindset of Jolyon Maugham.

And yet the scripts, soundtrack and cinematography (in their heyday managed by Gerald Thomas and Talbot Rothwell) all betrayed a fond attachment to our perceived eccentricities and insularity, our vulgarity and naivety. At the heart of each film, no matter their era and setting, were ordinary, everyday folk who kept budgerigars and polished their cars on Sunday, who got on with their lives without complaint until such time as they were driven together in minor rebellion against footling officialdom or sententious authority — and won in the end.

Even in the Carry On “histories” this theme still prevailed. From Hengist Pod in Cleo to Ken Biddle in Doctor, the little man and his friends emerged the victors. To this extent the series was the progeny of Passport to Pimlico, The Titfield Thunderbolt and other classic Ealing comedies of the pre-Lady Chatterley era, and back beyond that to the tradition of music hall.

The jokes could be topical. In Up the Khyber (1968), released as Britain experienced a wave of economic shocks and industrial unrest, Kenneth Williams’s Khasi of Kalabar warns his daughter, Princess Jehli, that his British prisoners will suffer death by a thousand cuts. When Jehli protests, the Khasi reassures her, with Williams’s trademark intonation, “Not at all my little desert flower, the British are used to cuts!”

In 1968 we laughed, for the joke rang true, and anyway it sounded funny. Even in the grip of another of those post-war crises, the British were happy to make fun of themselves. Could we do that today? Would we dare? In 2025 there would surely be a tsunami of complaint from po-faced X warriors about “record funding” for teachers and nurses, not to mention outrage at Williams playing an Indian prince? Imagine what Disney would do to Kenny and Joan Sims?

eels during the filming of Carry On At Your Convenience, 1971 (photo credits: Larry Ellis Collection/Getty Images; LMPC via Getty Images)

For what the Carry On world conveyed, and what we seem to have misplaced, is our historic sense of national identity, in which all Britons are part of the same tribe, not split into vicious and suspicious “communities” each competing for attention. In Convenience (1971), the lavatory factory works outing sees management and labour together on the same charabanc tour of Brighton where bowler hats and cloth caps caper together in a bawdy romp by the sea.

In Camping (1969) the middle- and working-class campers unite to repel the unwanted arrival of Woodstock-like flower children in the field next door. Society may have been stratified, but it was not divided in the way that it now appears to be.

Nor was there the same modern obsession with youth. In Carry On-land, even ugly men (James and Bresslaw were the kind of oil paintings Dorian Gray might well have kept locked in his attic) could still get the nice girls, and nice girls did not have to be stick insects or plucked, primped and permed to within an ace of their philtrum to get a look-in. Long before Love Island, Carry On Loving gave immeasurably more people immeasurably more hope for their future happiness.

Of course, Carry On does not speak to everyone. For some it is a world that taste forgot. But I think that is to misunderstand what lies at the heart of the Carry On appeal and what we left behind when we waved goodbye to it. It is not the character stereotypes nor the low budget locations. Nor is it the endless stream of innuendo. At its irreducible core, the Carry On series holds up a mirror to a society that was orderly and optimistic, a cohesive community of people who knew, and were at ease with, themselves.

That coherence, that easy familiarity which allowed space for self-parody, has largely been lost in the decades since, so that when we watch the films today, we see a land strange to our eyes, though we may instinctively recognise it as our own. Can we recover any of it, and should we even try? The actors, excepting Jim Dale, are all dead, and the people and the places they represent have gone, too. But would it not be nice to have a little silliness leaven some of our present sadness?

Surely there is room for a modern reboot of a franchise that laughs at us kindly and not cruelly, and so that elegy does not become eulogy. Might this just be a case of Carry On Dreaming? Well, perhaps not. For from the past another L.P. Hartley character, Leo Colston, sends us an answer: “Try now, try now, it isn’t too late.”