I lived and worked in Scotland half a century ago, and decided this year to revisit The Borders. This was partly in order to enjoy the remains of the great ecclesiastical foundations established during the reigns of the three sons who succeeded Malcolm III Canmore (r.1058-93) and his English Queen (from 1070), St Margaret (c.1045-93), notably David I (r.1124-53), partly to revel in the enchanting, underpopulated landscapes (and relatively uncrowded roads), and also to visit some fine country houses, for The Borders is still blessed with numerous large estates, and it was Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), 1st Baronet from 1820, who, more than anybody else, shaped the identity of the region. Until the second half of the 20th century, thanks partly to the continuing use of local building materials and the educated taste of generations of improving proprietors, that identity largely survived, but was damaged and threatened by the usual imposition of insensitive Modernist buildings employing concrete and other inappropriate materials that cannot be dignified by being called “architecture”, and ignore context, established urban fabric, and even landscape: the ignorant imposers have committed an æsthetic crime, wrecking harmony, civilised environments, and the legacy of men and women far nobler and greater in every way than themselves.

Soon, even on the first day of the week-long trip, however, unease began to make itself felt. 20 mph speed-limits in towns and villages were ubiquitous, and where there were road-works, single-lane one-way traffic was not only regulated by lights, but by a convoy system, when a vehicle, proceeding at a ridiculously slow speed, would lead traffic along the lane. Sometimes roads were closed altogether, involving enormous diversions, inevitably incompetently signed, so guaranteed to waste as much time as possible and infuriate drivers not familiar with local roads and lanes. It became clear that excessive attention to “Health & Safety” was being rigorously applied, and was not confined to speed-limits or traffic either. One began to wonder if goons carrying red (or perhaps rainbow) flags would soon be walking in front of lines of traffic in built-up areas.

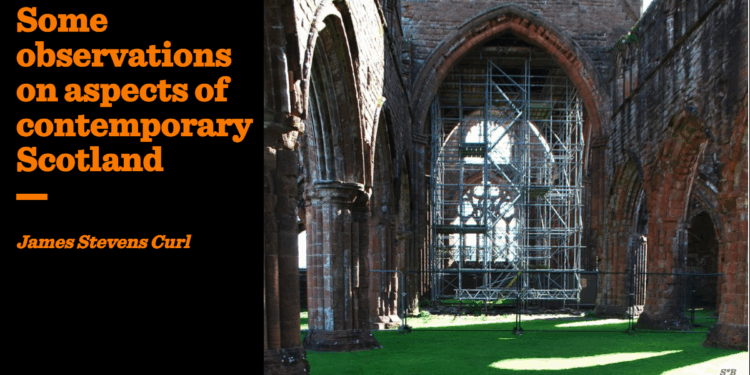

I stopped in Jedburgh, and visited the impressive ruins of the Abbey, standing on a series of terraces rising above the Jed Water. The site appears to have had a very long monastic history, stretching back to the early 9th century when a religious foundation was established there connected with Lindisfarne. The later community was founded around 1138 by David I, who brought Augustinian Canons here from Beauvais, and Jedburgh became a full Abbey around the middle of the 12th century, building continuing well into the 13th century. However, Jedburgh’s proximity to the border with England made the Abbey vulnerable during the many wars with Scotland’s southern neighbour, and there was considerable destruction during the 16th-century religious upheavals, which were particularly violent in Caledonia. Nevertheless, what survives at Jedburgh is still imposing.

The nave, too, ought to be worth exploring, but here there are ominous barriers keeping one at a distance, and this abomination recurs in The Borders and Galloway, not, apparently, to facilitate restoration and repair, but to prevent the possibility of any item of masonry from falling on a visitor’s head. They still charge visitors for the privilege of entering the site, but one is restricted, in some cases very severely. Health & Safety gone mad. In Jedburgh’s case, I was interested in making comparisons with certain architectural features at Romsey Abbey in Hampshire, where rebuilding works were carried out at a similar time to those at Jedburgh. Considering that King David’s aunt, Christina, was a nun in Romsey, the connection certainly is intriguing, but irritating barriers managed to prevent as much detailed observation as I would have liked. The west door was very elaborate, with six Orders, the five outer ones carried on slender shafts (all missing now), above which are three gablets set above a string-course. The rich decorations of the doorway have echoes in the west door of Kelso Abbey, and the treatment of the chevrons has certain parallels at Selby Abbey in Yorkshire.

After a not entirely satisfactory overnight stay in a rather grim hotel in Hawick, where service was begrudged, and they had insufficient fruit for breakfast (the “coffee” was unrecognisable as such), we escaped to look at Melrose Abbey, the first house for the Cistercians in Scotland, again established by David I, who brought monks from Rievaulx in Yorkshire. The ruins have long been a major source for artistic and architectural inspiration, not least to Sir Walter Scott, but I was furious to find barriers everywhere preventing me from seeing what I wanted to see, notably models for bits of the spectacular Sir Walter Scott Monument, that vast Gothic shrine that graces Edinburgh’s Princes Street, erected 1840-6 to designs by George Meikle Kemp (1795-1844). The lower parts of that noble creation were derived from studies of the remains at Melrose, with other higher elements drawing on precedents from Reims, Rouen, and the Cathedral spire at Antwerp. The scale of that huge canopy is exactly right for its site, but the statue of Sir Walter which it shelters (by John Steell [1804-91]) is far too small: it should have been twice the size it actually is.

Melrose is particularly interesting, not least because some of the window-tracery betrays a strong English influence. This followed the devastating assault on the Abbey by English troops in 1385, after which an almost total rebuilding was carried out, including an early contribution by King Richard II of England (r.1377-99), who may even have provided the master-mason for the job, although we know that a Parisian mason, one John Morow (presumably Moreau), was active at Melrose during the first decades of the 15th century, most importantly introducing Continental influences, eagerly accepted by the Scots as reaction against English ideas. However, barricades, scaffolding (no sign of anybody doing any actual conservation work, though), and high charges for the privilege of viewing ruins largely hidden behind said scaffolding and barriers, were all too much, so we repaired to Burt’s Hotel in Melrose for a spot of luncheon washed down with a potable pint of Timothy Taylor Landlord Bitter, the most enjoyable nosh we had for the whole trip, consumed in a place that had avoided the worst excesses of tasteless “modernisers” and that awful breed of interior designer which has no clue about what makes an agreeable country hotel or inn. As the late, great Roderick Gradidge (1929-2000) sagely observed, “Modernism never sold a pint of Bitter”.

Fortified somewhat, we moved on to that magical wooded loop of the River Tweed within which nestles what is said to be the most beautiful of all The Border Abbey remains, probably the first Premonstratensian Abbey in all Scotland, founded around 1150 by Hugh de Morville (d.1162), Constable of Scotland, and friend of King David I, who brought Canons to Dryburgh from Alnwick in 1152. What is left of the Abbey stands within a very pretty graveyard, and parts of the surviving fabric, the north choir aisle, shelter the tombs of Sir Walter and Lady Scott (née Charlotte Charpentier [1770-1826]) as well as that of John Gibson Lockhart (1794-1854), Scott’s biographer and son-in-law, with a bronze portrait medallion by John Steell. Nearby, in what was once the north transept, lie Field Marshal Douglas Haig (1861-1928), created Earl Haig of Bemersyde after the victory of 1918, and his wife (from 1905), the Hon. Dorothy Maud Vivian (1879-1939): their graves are marked by the standard headstones used in British military cemeteries. To say that the jury is still out on Haig’s direction of British forces on the Western Front would not be an exaggeration.

Two more features deserve to be noted: the first is the south-east processional doorway from the cloister to the nave, a fine Romanesque piece of around 1200, having three Orders with disengaged shafts, and an inner Order with massive dogtooth enrichment, and the second is the west gable of the former refectory with its 12-petalled 15th-century marigold window very similar to that in the west gable at Jedburgh.

Nothing more than fragments of the great Tironensian Abbey at Kelso survive, although those which do (all at the west end of the church) are impressive. Another foundation of David I, the architecture is powerful Romanesque, not least the north doorway, the main lay entrance to the church set within a salient section of wall capped by intersecting arcading set below a triangular gable enlivened with diaper decoration.

Meanwhile, although we had had tolerable accommodation (mostly) in The Borders, we had lukewarm kippers at breakfast two days running, and on our last morning in one establishment they had run out of the berries and so on, which they knew we liked for breakfast: I thought that was worse than careless, and bordered on incivility. Food generally was at best mediocre, coffee generally unrecognisable as such, and to be treated as though one hails from Outer Space when one requests unsalted butter is always a bad sign. In one establishment, supposedly a highly esteemed and recommended inn, any draught beer was so cold one would have danger of getting frostbite if one tried to sink any of it (let alone hold a glass containing the freezing liquid for any length of time), and, besides, most of what was on offer was of the blonde, excessively citrus-flavoured type — unacceptable to any connoisseur of traditional ales. Wine-lists were on the whole very disappointing and very ordinary, as well as being grotesquely over-priced.

We proceeded westwards into Dumfries & Galloway, where we stopped in New Abbey to revisit one of the best-preserved remains of any mediæval monastic foundation in Scotland. Founded as a Cistercian establishment by Derbhforgaill (Dervorguilla) de Balliol, Lady of Galloway (c.1210-90), widow of John de Balliol (before 1208-68), Lord of Barnard Castle, magnate and benefactor. The Statutes of what became Balliol College, Oxford, were formulated in 1282 by Derbhforgaill, who, after her husband’s death in 1268, kept his embalmed heart set within an ivory casket always by her side, and founded the Abbey of Dulce Cor (Sweet Heart) in 1273 in his memory. After her own death, she left instructions that the casket should be laid “betwene hyr pappys twa” and that she should be entombed in the Abbey accompanied by the heart, tastefully placed in that privileged position. Now the Abbey church was erected in honour of God and the Blessed Virgin Mary, so Dulce Cor could well apply to more than one meaning.

It was infuriating to see scaffolding still in abundance on the church tower after about a decade, during which, having passed the place umpteen times, I have never seen anybody working on the stonework. Inside the nave, barriers and scaffolding prevented inspection of anything eastwards. Adjacent to the Abbey church is a large burial-ground which contains the resting-places of numerous friends long gone. Among the burial-enclosures therein is that of the Stewarts of Shambellie, their Achievement of Arms set over the entrance, but there are disquieting signs in rather too many Scots graveyards indicative of a pernicious nannying that is merely an excuse for widespread official vandalism. Many tombstones and monuments are being toppled, just in case youthful vandals trying to push over memorials might get hurt, so local authorities do the pushing for them. This, together with absurd speed-limits, barriers, scaffolding, and much else of a prohibitive or restrictive nature, suggests a very disturbing tendency in contemporary Scotland that is essentially extremely destructive, a kind of suffocating, modern, controlling iconoclasm knocking the stuffing out of life itself.

To the east of New Abbey, not far from Kirkudbright, are the rather wonderful remains of another Cistercian foundation, a daughter-house of Rievaulx, at Dundrennan, perhaps founded at Soulseat by St Malachy (Máel-M’áedóc) of Armagh (1094-1148) in the year of his death, moving to Dundrennan in or after 1156. What survives is largely the late 12th-century presbytery and transepts, but the setting is spectacular. Considerable fragments survive of what was an ambitious 13th-century stone choir screen (details of which were published in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 137 [2007], 405-432).

All in all, then, it was a not altogether satisfactory trip, because much of the detail I wished to study in Abbey ruins was hidden from view, and there were many disquieting aspects of modern Scotland that seem to have ballooned in recent years: it is not the country in which I lived fifty years ago. Many of those aspects seem to derive from a kind of petty nationalism combined with Anglophobia, class prejudices, and the embrace of extreme tendencies concerning gender, Middle Eastern fracturing, and overt hostility towards anyone not (or perceived as not) adhering to Leftist Received Opinion. Rory Knight Bruce wrote of “wrestling” with “nationhood”, and the “backward glances of a coward, from which will come no future good”. Indeed so: a remark that chimes with my own feelings.

Perhaps some of the malaise is best summed up by that insult to the venerable fabric of Auld Reekie itself, the Scottish Parliament Building (1998-2004), sited at the foot of the Royal Mile, opposite Holyrood Palace, the design of which was won in 1998 by the Catalan architect, Enric Miralles Moya (1955-2000). I understand that when Miralles Moya was taken on a brief tour of Scotland to “understand the context” (a fat lot of good that did!), the party briefly strayed into northern England where the Catalan was greatly taken by the sight of upturned boats, for some reason. To him those appear to have represented boats being built in towns and then moving on elsewhere, so for some weird reason he incorporated shapes based on upturned boats as part of the over-complicated roof-structure. Apart from the highly questionable logic of such allusions, the roofs leak, and still do.

An Italian architect, Benedetta Tagliabue (b.1963) had joined forces with Miralles Moya, marrying him in 1992, so she was also involved in the design of the Edinburgh building. At a lecture in Barcelona, she appears to have suggested that earth was something typically Scottish, and so cutting into it was also typically Scottish, which, if an accurate résumé of what she said, would at the very least be questionable. Modernists tend to indulge in such supposedly gnomic utterances as part of their elaborate linguistic dances in order to justify their excesses: such are the bullying, bamboozling tactics that few are capable of questioning them, yet every statement from any Modernist needs to be examined, unpicked, analysed, and shown up for its pretentious emptiness. Matters became ever more bizarre when it was claimed that the applied “decorations” around the outside of the Parliament draw inspiration from the painting, The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch (c.1784), by Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823): they more resemble hair-dryers, though what such objects or the Revd. Walker might be doing plonked around such a structure defies the imagination and any sensible reason. In addition, they are supported by hidden fixings, and provide one of the best nesting-spots for seagulls in the Scots capital, with the inevitable result that bucket-loads of guano have to be cleared out at regular intervals. If we are honest, those stuck-on “decorations” have no meaning whatsoever, nor did all the trumpeted study of “context” bring any benefits, for the building insults its context and has no connection whatsoever to indigenous architecture of any period, especially ignoring the great Classical architectural legacy that was such an essential element in the built fabric of the city.

Scotland was once a land with a splendid and unique heritage of great architecture (something to which Sir Walter Scott gave new impetus, notably by constructing his marvellous house at Abbotsford in The Borders with William Atkinson [c.1774-1839] as executant architect). Scott’s superb library demonstrated to me that he was no small-minded nationalist, but a great European Man of Letters, with a considerable collection of important books in German and French. I wonder what he would think of a loutish interloper like the Parliament building (and, indeed, of those who inhabit it)? Is this yet another instance of the ignorant and insensitive turning their backs on that great heritage in order to acquire a so-called “iconic” building at great expense (with maintenance-costs mounting each year), devoid of meaning, stuffed with banalities and extremely tenuous, even absurd, allusions, all to be able to claim a spurious “Modernity”, yet at the same time attempt to conceal a queasy sense of national disappointment?

I do not think it was odd or even surprising that many local newspapers in The Borders and elsewhere reported that Scots Jews were feeling increasingly insecure, given some of the utterances and actions of politicians and commentators (and this was before the Manchester attack). I might also suggest that many reasonable, civilised, sensitive, educated people from many backgrounds and walks of life might feel a growing unease in contemporary Caledonia. Excessive “wokery”, nannying, and insularity can be extremely unhealthy, and that, I fear, is exactly what is on the cards today.