This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Sometime in the 1870s, music learned that its evolution had not been organic. Rather than rising in small incremental notches like a graph on a business account, it looked more like the Himalayas — a range of half-glimpsed peaks with fertile plateaus in between. The summits were known as Great Composers, and this was the origin of the species.

GC theory was an offshoot of Thomas Carlyle’s idea that world history “is at bottom the History of the Great Men”. Where Carlyle listed Muhammad, Shakespeare, Rousseau and Napoleon as world changers, musicians in the 1870s recognised that Italian opera, without Verdi, would be trivial and without Wagner there would be no German opera at all. Great Composers tear up and redraw the map of music, Q.E.Die Meistersinger.

In the past, Haydn looked back to Bach; Mozart called Haydn “the father of us all”; Beethoven doffed his hat to Handel; and Chopin owed it all to Schumann, random credits. Now, musicians were conditioned to look ahead to the next big influencer.

There were plenty of contenders in late romanticism, from Tchaikovsky to Mahler. Modernism split between the Debussy-Sibelius cruise line and the Schoenberg explorer. GC debate yielded much dynamism until the record industry leaped on the tug-boat and boxed anyone who wrote six symphonies into a Great Composers multipack that fitted on a bookshelf beside Great Writers from Goethe to Graham Greene. That was culture before it went multi.

And then it crashed. Stravinsky’s death in 1971 marked the last of the great composers. No living name could now be dropped at a dinner table except, maybe, Shostakovich, who died four years later.

Since then, the shelf has gone bare. For the last half-century, no concert or opera composer has made a scratch on public awareness. The passing of Harrison Birtwistle, Britain’s most striking sound maker, failed to make a headline on BBC News. Great Composer theory had fallen into a hole where it was dumped on by feminists as a cult of dead white men.

It was obsolete in other ways. In an increasingly authoritarian age, we are suspicious of new leaders; when posterity squints back at us it will have to fumble in the dark to identify 21st-century composers who might, by some future criteria, qualify for greatness.

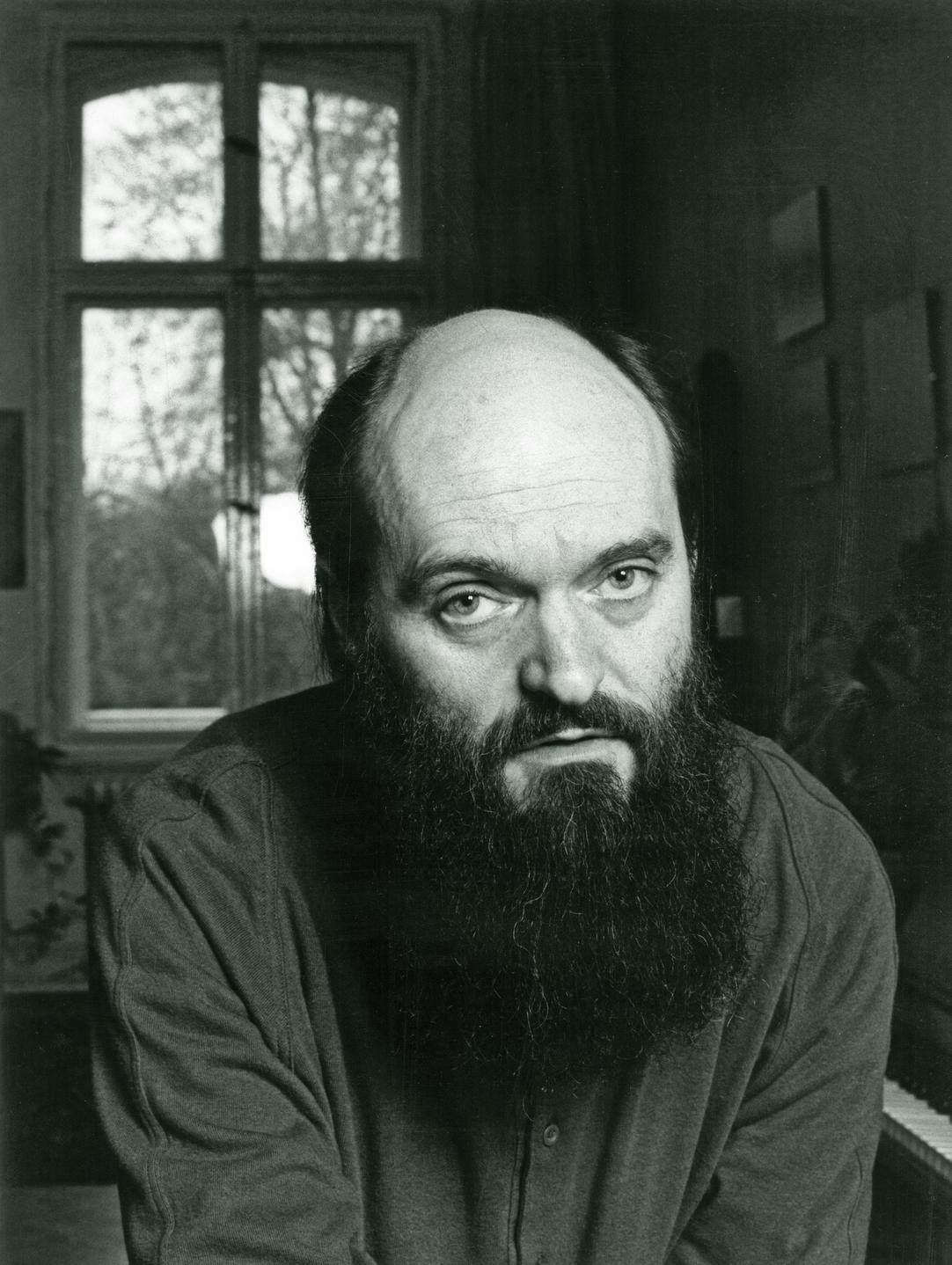

Ask me nicely, and I’ll propose one or two. Deep in an Estonian forest you will find Arvo Pärt, 90 last month and exercising more influence than ever. An angry atonalist under Soviet rule, Pärt stepped back into a contemplative minimalism that mocked state atheism with pure spirituality and responded with unhurried naturalism to the strident re-re-re-repetitions of American minimalists Steve Reich and Philip Glass, so urban and anxiety-ridden by comparison.

Works like Fratres and Pärt’s third symphony felt timeless on first reception. Pärt has outlasted Bolsheviks and Boulezians, critical dogmas and changes of fashion. I keep hearing new concert works by young composers that sound like semi-skimmed Pärt.

Björk, Radiohead and other rock stars cite him as an inspiration. He speaks to our time and beyond without a smidge of self-promotion. Arvo Pärt is one for the ages.

The other sleeping giant requires a mea culpa. Early in the millennium, I wrote an essay deriding John Williams as “the magpie maestro” without an original idea to call his own.

My ears were trained on a Harry Potter film score that drew on Mahler, Prokofiev, Rimsky-Korsakov and Ravel, taking further leitmotifs from Debussy (“Knockturn Alley”), Smetana (“Colin”) and Holst (“Moaning Myrtle”). My analysis was factual and I stand by every word.

What I missed was the buried truth: John Williams, for all his klepto tendencies, is a unique and original voice of our time.

The conductor Leonard Slatkin puts his forefinger on it one-third of the way into Tim Grieving’s hugely engrossing new biography of Hollywood’s premier composer. Beethoven, says Slatkin, took four notes to create the signature theme of his fifth symphony. John Williams, in Jaws, does it in two. “Two notes!” exclaims Slatkin. “You know what that is! There’s somebody whose legacy is assured.”

The shark movie, 50 years old, launched Williams’s partnership with Steven Spielberg, a close encounter that bears comparison with Mozart and Da Ponte in the symbiosis they found in each other. Williams was 40, 15 years older than Spielberg and a master craftsman, never without a film on the go, when an appalling tragedy halted his progress.

His vivacious actress wife Barbara, the love of his life, was found dead of an aneurysm whilst working on a Robert Altman film. Williams, with three teenaged children to raise, withdrew into himself, barely communicating.

Spielberg introduced him to George Lucas. He went on to compose Star Wars. Still in outer space, he rejoined Spielberg for Close Encounters of the Third Kind. His versatility was limitless. In Schindler’s List, the non-Jewish Williams made violins weep in Yiddish. He confessed that his first-ever Oscar was for rescoring Fiddler on the Roof.

Between awards, he had André Previn in his ear urging him to get out of Beverly Hills and compose serious schtick for orchestras. Williams zipped back with a 12-tone score that Schoenberg would have approved.

He wrote a symphony that got lost somewhere as well as concertos for various instruments, all of them box-office gold. These days, at 93, John Williams gets to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic, just like Gustav Mahler.

There are no short measures in his scores. Each is a work of art that will endure as long as his movies are shown, which is forever. John Williams is, by any reckoning, a Great Composer. He may yet revive the species and renew orchestral faith.