Many moons ago at the Christening of one of my children in St Agnes Church, Kennington, I noticed that Nigel Farage was standing up and down at all the right moments of the service without prompting. Decades after visits to Dulwich’s chapel this feat of memory was pretty impressive, so I mentioned that he knew his way around a service. “Oh he is quite devout, but doesn’t go on about it,” Kirsten his then wife, told me. Of course as an Anglican that is sort of the point.

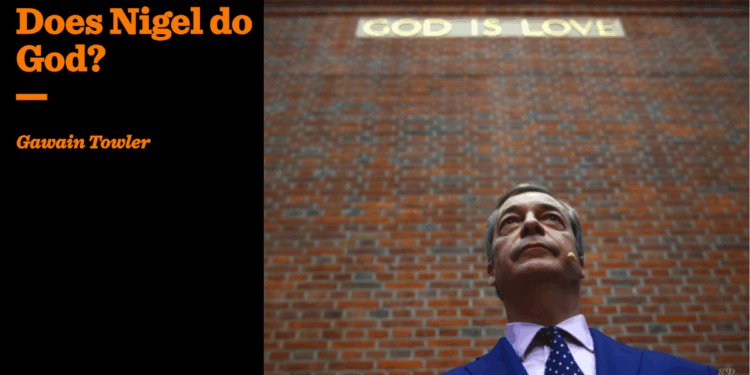

That understated devotion came to mind again this week, following Farage’s candid exchange with Mishal Husain on Bloomberg. When asked if he was a “man of faith,” the Reform UK leader replied, “Yes. I have to say, struggling a bit.” Probed on church attendance, he affirmed, “Well of course, I’m an Anglican, it’s been a catastrophe for 25 years … If I was a more regular churchgoer I would probably have defected to the Catholics.” But, as Husain pressed, “You haven’t?” Farage admitted, “I haven’t, but I have thought about it a couple of times.”

This glimpse into his spiritual life, hesitant yet honest, reveals a man whose faith, though private, has an influence on his political mission. In an era where politicians flaunt virtue like Instagram influencers, Farage’s reticence to reveal all is refreshing. It’s not calculating like Tony Blair’s post-Downing Street admission that he was a Catholic, but a deeply personal anchor that shapes his vision for Britain.

Since that christening encounter, discussions of Farage’s faith have been rare. He isn’t one to echo Alastair Campbell’s infamous rebuke to Blair: “We don’t do God.” For Blair, everything was a stage-managed spectacle; for Farage, matters like faith and family are sacred and not a thing to manipulate for public consumption.

Yet, as his Bloomberg admission suggests, this private conviction does inform his political belief system. The triad of Family, Community, Country that defines Reform UK’s manifesto draws directly from Judeo-Christian roots. Farage has long argued that the UK, and England especially, is a product of these values, moral absolutes that foster social cohesion, personal responsibility, and national pride. It’s no coincidence he voted against the assisted dying bill, viewing it as an erosion of the sanctity of life, a stance echoing traditional Christian ethics. A few months ago I noticed a biblical phrase or two appearing in his speeches, talking about a membership recruitment drive, he called on members to become “fishers of men”.

Orr’s appointment signals a shift toward traditional Christian thought in policy-making

This isn’t the first time Farage has touched on faith publicly. Back in 2015, as UKIP leader, he called for a “muscular defence” of Christianity in the UK, insisting the nation is “fundamentally a Christian” one whose heritage should be recognised at all government levels. UKIP’s manifesto then championed policies infused with Christian concerns: banning sex-selective abortions, maintaining laws against euthanasia, combating human trafficking as a modern abolitionist cause, supporting faith schools and protecting church infrastructure through tax relief. He even advocated a “reasonable accommodation” for believers refusing services to affirm same-sex couples, a pushback against what he saw as secular overreach. They reflected a worldview where Christian principles guide policy, from family protections to cultural preservation.

Fast forward a decade to today and this thread persists. Farage has distanced himself from the Church of England, lamenting its “surrender” to the “woke agenda” as a reason he no longer attends. He criticises its leadership, implicitly figures like the previous and incoming Archbishops of Canterbury, for being “upper middle class, completely detached from reality.”

This mirrors the quiet frustration of many churchgoers I encounter while exploring beautiful parish churches across these islands. They‘re loyally hanging on, despite the Church squandering resources on graffiti art, reparations debates and payouts, and trendy causes that alienate the faithful. These parishioners feel treated as inconveniences, much like how Farage’s supporters view the establishment’s disdain for ordinary Britons. It’s a potent metaphor for Reform’s appeal: a revolt against institutions that have lost their way, prioritising ideology over core values.

Data backs this alignment. Research from the Theos think tank shows “non-practising Anglicans”, cultural Christians who don’t regularly worship, as the “ideal Reform voter.” They‘re authoritarian-leaning, nostalgic for a Britain rooted in Christian norms, disillusioned with progressive drifts in both church and state. Reform taps this vein, positioning itself as the defender of these values. As one analysis argues, it’s the “best option for British Christians,” advocating immigration policies that prioritise Christians, opposing transgender ideology, and supporting traditional marriage through tax incentives for wedded couples and stay-at-home parents. Farage’s old call for favouring Christian migrants over others stems from this: a belief that assimilation thrives on shared cultural foundations.

His policies extend this faith-informed ethos. Reform’s push for law and order, affordable housing, and pension improvements resonates with a Christian emphasis on justice and care for the vulnerable, without the woke baggage. On free speech, the party vows to cut funding for censorious institutions, protecting Christians’ right to express views on marriage and sexuality. Even economic prescriptions, like raising the income tax threshold and promoting small businesses align with a vision of self-reliant communities.

The recent promotion of Professor James Orr to Farage’s inner circle underscores this deepening Christian influence. Orr, a Cambridge philosopher of religion and convert via a profound encounter with the Greek New Testament, brings intellectual heft. A right-wing theologian, he’s linked to figures like JD Vance and conservative think tanks. Tasked with talent acquisition for Reform, his appointment signals a shift toward traditional Christian thought in policy-making. Though critics decry it as anti-LGBTQ or anti-abortion extremism, it just isn’t. Though for Farage’s base, it’s a welcome bulwark against cultural relativism. Darren Grimes, the Deputy leader of Durham County Council, and a very out gay man is a recent convert, confirmed in by Father Marcus Walker in St Bartholomew’s a few years ago. And there are many others.

I don’t see Farage’s “struggling” faith as a weakness. I see it more as authenticity in an age of cynicism. And it should fuel policies that reject the establishment’s secular drift, championing a Britain reborn through a restoration of our shared but half-forgotten Christian values. As Reform surges, this quiet piety could prove the secret weapon in reshaping our politics, not with sermons, but with substance.