Watching the BBC interview with Amy Wallace, co-author of the late Virginia Giuffre‘s posthumous memoir Nobody’s Girl, which was published yesterday, I was struck by something she said.

‘Virginia wanted all the men who she had been trafficked to, against her will, to be held to account, and this is just one of the men,’ she said. ‘Even though he [Andrew] continues to deny it, his life is being eroded because of his past behaviour, as it should be.’

‘As it should be.’ Prince Andrew should take heed of that. It is clear from what Ms Wallace says that the ghost of Virginia is going to haunt him to his grave – or until he finds himself shivering in a jail cell like his old friends Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. This is not just any memoir, it’s a revenge memoir.

Giuffre’s book isn’t the only thorn in Andrew’s side, of course. There is also the Chinese spies affair and the revelatory emails between him and Epstein.

Both have shown him in a deeply unsavoury light, particularly the latter which – as well as being deeply creepy (‘we will play again soon’ etc.) – expose him as a liar. Together all three are a devastating storm.

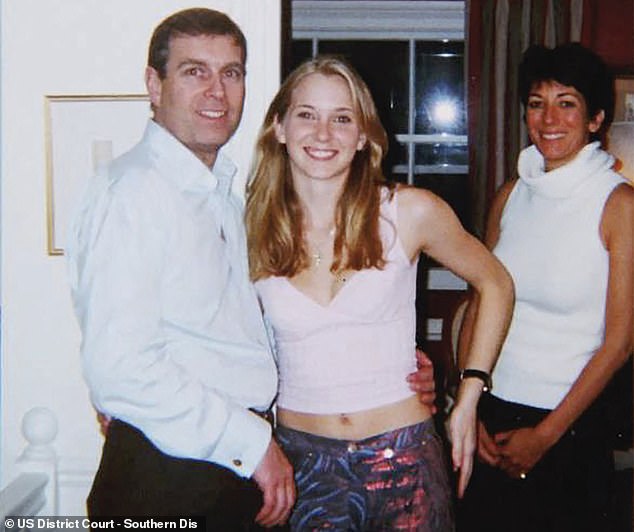

But it’s Giuffre’s own account, I think, that strikes at the heart of all this. It’s her story that really shifts the focus away from titles and grace-and-favours and acts of parliament and all that high-stakes stuff, and brings it back round to what it’s really about: that lost, vulnerable 17-year-old girl in that photograph taken all those years ago.

It’s about power and privilege – and the abuse of both. It’s about an aristocratic mindset that hasn’t really changed in centuries, a droit du seigneur that still applies in the minds of far too many men of a certain class and upbringing.

It’s about how girls like her are treated by men like them, and about how they’ve always – until now – got away with it.

That line in Giuffre’s book – where she writes about the first time she allegedly met the Prince in 2001 and how he allegedly correctly guessed her age, adding, ‘My daughters are just a little younger than you’ – is a killer. In a way, it says it all.

The ghost of Virginia Giuffre (centre) is going to haunt Prince Andrew (left) to his grave – or until he finds himself in jail like his old friends Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell (right)

Andrew would have been around 41. Any normal father in those circumstances would have sobered up (if not literally then morally), made his excuses and left. But he did not. She says he went on to have sex with her anyway, although he denies it.

Assuming her account is true (and of course we can never know for certain), it’s clear that at that moment Andrew did not see Virginia in the same light as his own girls. Otherwise, how on earth could he have had sex with her?

In his mind she must have been in an entirely different category of… what? Peasant? Damaged goods? The kind of girl already so broken it didn’t really matter what happened to her? Just a pretty piece of fun, nothing more than a plaything, without emotions or feelings of her own? Someone who, ultimately, didn’t matter. Forgettable even, as he himself has always claimed.

There’s a cruel kind of heartlessness in that, isn’t there? I wonder how Giuffre must have felt when Prince Andrew said he couldn’t even remember meeting her. A moment that defined her entire life – yet didn’t even register in his. How worthless that must have made her feel.

It’s that casual dismissal that really stings, reflected also in the exchange between Virginia and Epstein during their first encounter. She’s brought into meet him by Maxwell. He’s lying on a massage table, naked.

She writes: ‘”Tell me about your first time,” Epstein said then. I hesitated. Who’d ever heard of an employer asking an applicant about losing her virginity? But I wanted this job, so I took a deep breath and described my rough childhood.

‘I’d been abused by a family friend, I said vaguely, and spent time on the street as a runaway.

‘Epstein didn’t recoil. Instead, he made light of it, teasing me for being “a naughty girl”.

‘”Not at all,” I said defensively. “I’m a good girl. I’ve just always found myself in the wrong places.”

‘Epstein lifted his head and smirked at me. “It’s OK,” he said. “I like naughty girls.”‘

Again, that sense, of Virginia being a ‘certain’ kind of girl. He had no interest in or sympathy for her situation, save that it made her easier to take advantage of. It’s every abuser’s first line of defence, isn’t it? She was asking for it; she deserved it; she was ‘that kind’ of girl.

But she was also 16, 17 when she met Andrew.

If it’s also true, as she claims in the book, that she was sexually abused by her father and one of his friends as a child, how was she supposed to know any better?

Pleasing men would have been learnt behaviour for her – arguably even a survival strategy.

Giuffre’s book comes as Andrew (left) is engulfed in the Chinese spies affair and the revelatory emails between him and Epstein (right)

Virginia’s is a story that happens to involve a Prince; but it is also one that reflects a wider pattern, present in so many cases of abuse. A damaged, vulnerable girl, an easy target for ruthless predators. Think, for example, of the Asian grooming gangs that preyed so relentlessly on poor white working-class girls: their own daughters were untouchable; but their victims were in a very different category, unclean and therefore fair game.

Whether it’s the backstreets of Bolton or a mews house in Mayfair, the mindset is the same: some girls are as disposable as a box of tissues.

In different times, they would have got away with it. But not now, not in a post #MeToo world that doesn’t automatically dismiss women as outright liars on the basis that they might not have had the best start in life.

Like it or not – and many do not – things are different now. Just as those brave girls in Rotherham and elsewhere confronted their abusers and – despite all the threats and intimidation and regardless of what shame or judgment might be piled upon their heads, sought justice not just for themselves but for future generations of girls – in her own way, Giuffre tried to do the same.

The grooming gangs hid behind political correctness and localised corruption; Epstein hid behind money and status and collected powerful friends like trophies.

I don’t believe for one second that Andrew was a serial abuser like him; but the fact that he accepted Epstein’s ‘gifts’ and kept his company even after he knew what kind of a person the late financier was does make him complicit.

Prince Andrew’s mistake was also to think he could buy her out with that £12 million settlement. Not only did it appear to be a tacit admission of guilt, but it also meant that Giuffre’s claims were never properly challenged.

Perhaps if they had been, he might not have come out of this in such a bad light. Then again, it might have made matters worse. We shall never know.

What’s certain though is that for a woman like Giuffre, who had been so badly used at such a young age, it was never really about the money.

It was about being seen as a person, not a commodity, about being valued as a human being, not a piece of meat.

Perhaps if Prince Andrew had been able to understand that, and to acknowledge their encounter and its significance in the wider context of her exploitation at the hands of Maxwell and Epstein, he might not have felt the full extent of her wrath.

But he didn’t. And because Giuffre – like so many victims of abuse – had nothing left to lose, she exacted her revenge.

Andrew – who by contrast had everything to lose – has been brought lower than anyone ever imagined was possible. He may yet sink lower still.