This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

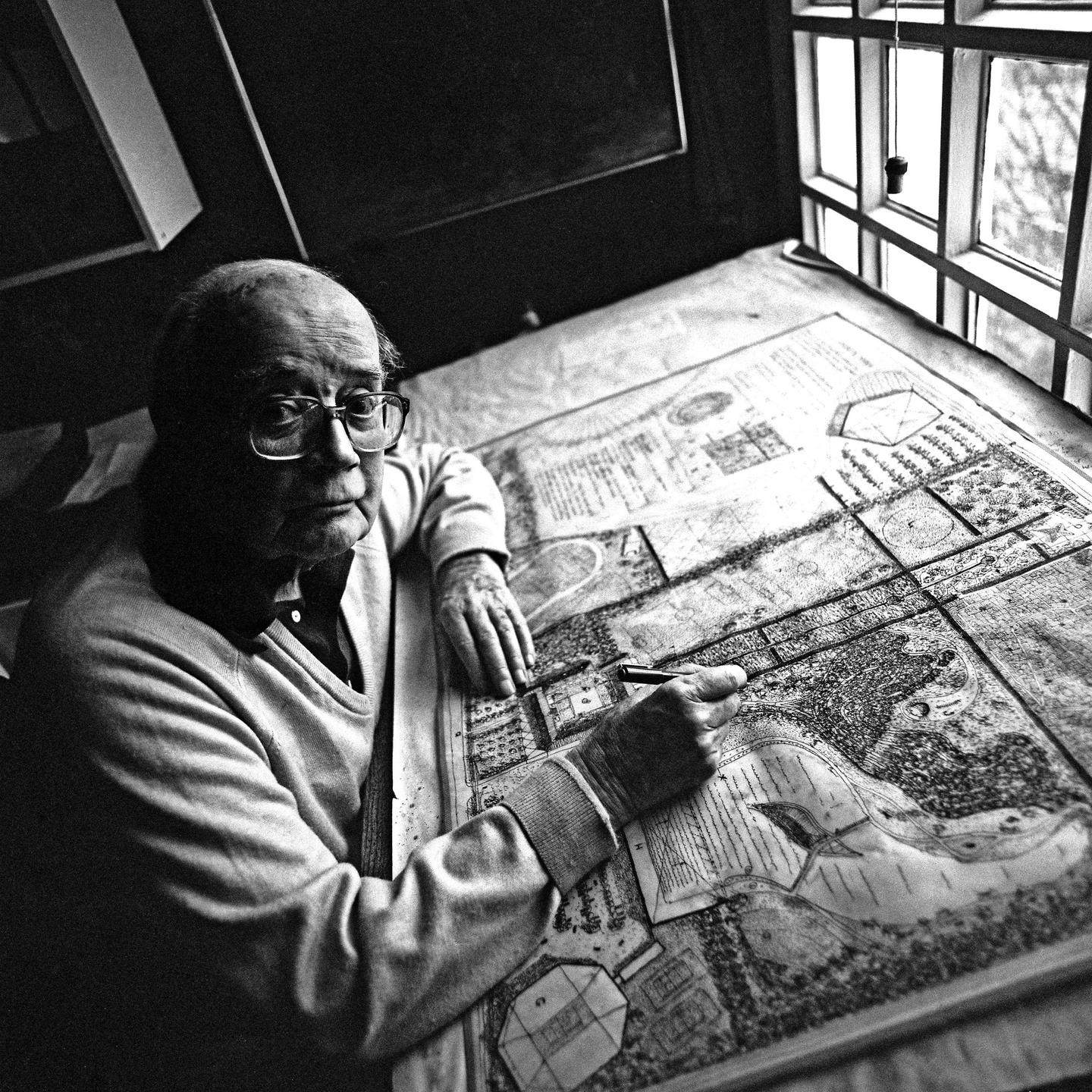

In 1975, Geoffrey Jellicoe — surely the most influential British landscape architect of the 20th century — made an audacious claim: “The world is moving into a phase when landscape design may well be recognised as the most comprehensive of the arts.”

His pioneering Landscape of Man, published 50 years ago, was a manifesto masquerading as a historical tour d’horizon. Landscape design, Jellicoe insisted, was no mere ornamental diversion, but the one art form capable of mediating between humanity and nature, reason and intuition, science and myth. It was, he said, society’s only true necessity.

Half a century later, where does his vision stand?

Walking through the opening night of the Design Museum’s More Than Human exhibition this summer, I wondered what Jellicoe would think now. On one level, he would feel vindicated. Public bodies in Britain are beginning to accept, if not embrace, nature recovery networks.

Large-scale projects — the Somerset Wetlands, Weald to Waves, Chalk to Coast, the Cambridge Nature Network, and new townscapes such as South East Faversham and Chapelton — are finally convening landscape architects, farmers, architects and conservationists as co-designers of a future healthy landscape. The creed that landscape is social necessity has, at least, filtered into policy papers.

But here’s the rub: the visionary imagination has slipped from view. For Jellicoe, landscape was never just ecological. It was also symbolic, allegorical, even metaphysical — “the invisible made visible”. His JFK Memorial at Runnymede, or the layered symbolism of Shute House, treated land as cultural text.

Since then, only a handful of mavericks — Charles Jencks’s Garden of Cosmic Speculation, Ian Hamilton-Finlay’s Little Sparta, Kim Wilkie’s Orpheus — have continued that tradition. The rest of us rarely aim higher than ornamental beauty, climate resilience and biodiversity gain. Indispensable objectives, but hardly the stuff of myth.

The biosphere may be healthier, but our relationship is not reimagined. In short, we risk constraining the most comprehensive of arts to a junior branch of land management. The natural capital accountants have arrived; the poets have fled.

But nature’s own voice may yet return as guide.

The Design Museum’s More Than Human explicitly overturns Jellicoe’s belief that “man’s place is to be above nature”. The exhibition’s premise is that we must design with nature — or even as nature. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s AI-generated Pollinator Tapestry makes the human designer redundant by using an algorithm to specify insect-attracting planting palettes. The MOTH Collective’s mural advocates legal rights for rivers. The whole exhibition is a pageant of species-level humility: Homo sapiens put back in his box.

Would Jellicoe have been horrified or delighted? Both perhaps. He might have resisted the dethroning of the designer, the suggestion that landscape can compose itself. And yet he also divided art into Fancy and Design: the imaginative and the rational.

He urged landscape architects to borrow vision from artists, who glimpse truths beyond time and space. In that sense, More Than Human radicalises rather than rejects his legacy.

From the Rumiti ritual, where men dressed as trees process through Basilicata hills, to Isabella Rosellini’s Seduce Me films, where she playfully enacts the mating rituals of bed bugs and sea horses, the exhibits explore the world through Fancy — reimagining futures beyond human design norms; embracing the “invisible made visible”.

And for those who find this all too esoteric, Marcus Coates’s Nature Calendar — a patient daily record through the year of wrens shifting seasonal song and eels slipping downstream — echoes Jellicoe’s conviction, and that of every good gardener, that close observation is the bedrock of understanding nature. And a successful crop.

All of this is as resonant now as 50 years ago. Our food system, biodiversity, the politics of land are not just ecological issues. They are cultural issues, which demand cultural solutions. Habitat corridors and healthy soils will keep us alive, but man does not thrive on bread alone. We need landscapes that articulate meaning, that confront mortality, power, belonging, transcendence. That is the scale Jellicoe imagined.

Like Jellicoe, the exhibition is provocative and compelling. Its challenge is clear: landscape design must move beyond stewardship to embrace co-creation — capable of shaping both land and meaning, of recovering the numinous, and of re-enchanting a culture that has forgotten how to see.