This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Look at the wreckage, from Ukraine to Gaza. Where there is less wreckage, note the air of growing menace, from Kashmir to Taiwan, or across the Ukraine-Polish border. Consider the unapologetic manoeuvring for power between the top dogs, as the US-led West demands more from its allies whilst promising less, and struggles to contain a new Eurasion axis of Central Powers, Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, now in a dalliance with India. See that Poland and South Korea openly think the unthinkable, contemplating acquiring nuclear weapons.

Note too the double dealing fair-weatheredness of onlooking regimes, denouncing Vladimir Putin or Benjamin Netanyahu whilst trading with them. Even commodities that are supposed to be part of global cooperation, such as lithium for the pursuit of green energy, are now the target of fierce contestation.

Under this darkening sky, the art historian Sir Kenneth Clark was right after all, half a century ago. Clark concluded his epic documentary Civilisation thus: “ … in spite of the recent triumphs of science, men haven’t changed much in the last two thousand years.”

How true. Progressive whigs, moral crusaders, idealist war hawks, revolutionaries and pacifists alike will roll their eyes, but sometimes the hardest truths are the simplest ones.

The main insight of realism, an ancient tradition, still holds. Realism is a way of thinking about international politics that stretches from Thucydides and Kautilya to Machiavelli to Morgenthau. It echoes in the medieval texts of Chinese strategists, or the ruthless diplomacy in modern times of the Anwar Sadats or Narendra Modis or wily small states like the Solomons. Realism has no monopoly over what is realistic — no tradition has that. Rather, it is a pessimism about the unchangeability of the world in its fundamentals.

For realists, we humans are born into a world where war is possible. War, and annihilation. And we are born into a state of anarchy, the lack of a supreme authority above the state. There is no benign sheriff who we can dial in extremis. In turn, this predicament makes self-help vital, state power central, and encourages similar behaviour. World politics is often competitive. But even when there are stable pecking orders, it is largely one of self-seeking under the shadow of war.

For realists, accepting the dark, baseline condition is essential in order to survive, avoid or win wars, and to secure things worth defending.

For realists, to be prudent is to comprehend any problem by starting with the world as it bleakly is, rather than what we would like it to be. Much of our foreign policy debate pivots on this question, and it’s harder than it sounds. We are aspirational creatures. Our public life is full of noble souls who cling to the hope that our species can change and create a different international life. Hence, as Machiavelli noted, “Many writers have dreamed up republics and kingdoms that bear no resemblance to experience and never existed in reality.”

It is hard for virtuous people to swallow realism. It seems amoral, even immoral. It seems oblivious to cultural difference and change. It seems too occidental, too implicated in orders of racist domination. Those indeed are the three main charges against realism, in every generation, that it is immoral, unrealistic and exclusionary.

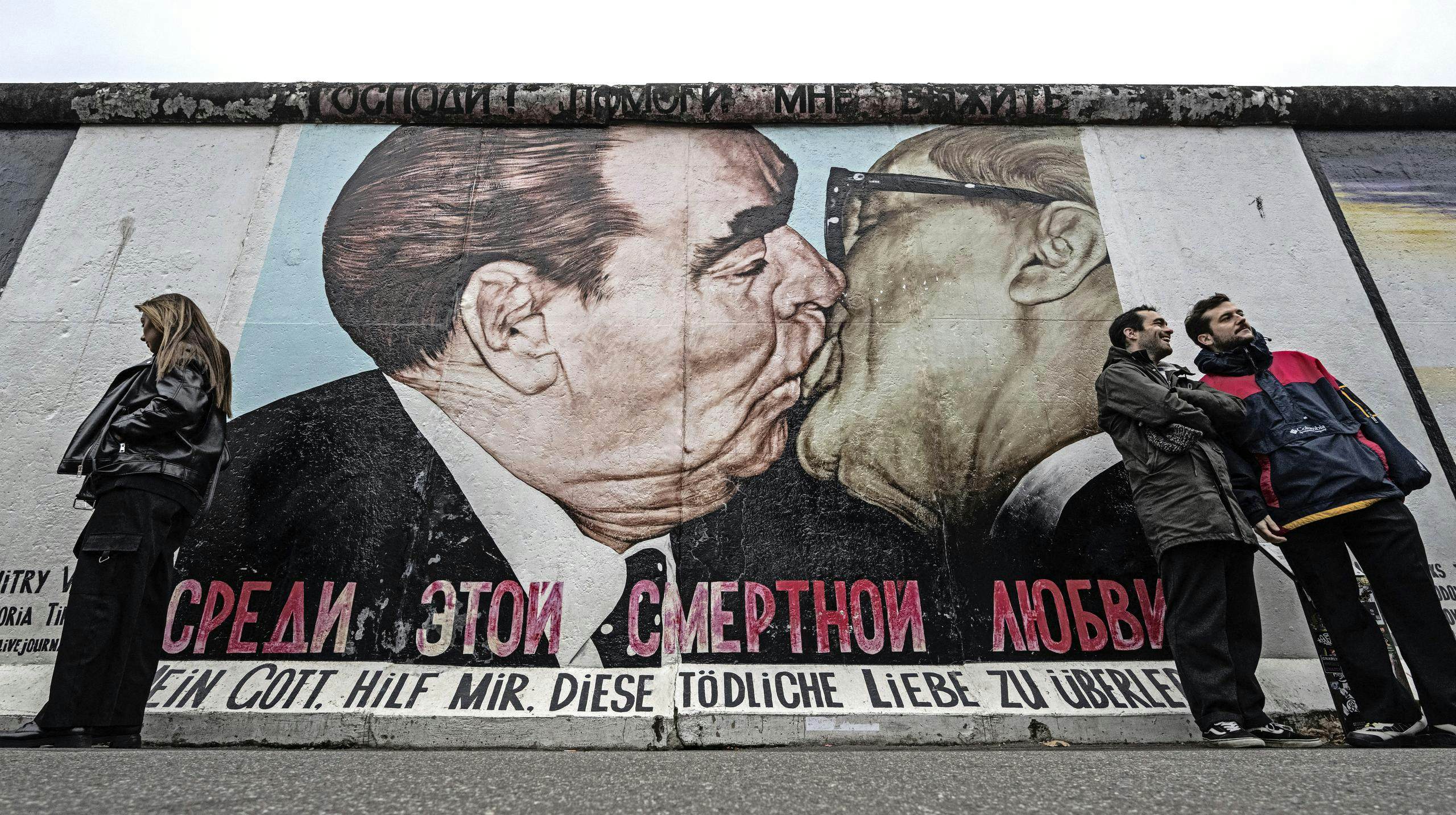

Not so long ago, international relations scholars and pundits could write off realism or announce its wake. When the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union fell without a shot fired, and when the American colossus stood tall without a peer adversary in sight, this “unipolar moment” made space for a thousand dreams.

This moment, optimists hoped, was more than a moment. The new Atlantic order marked the permanent transformation of the world. Power politics — the adversarial contest for the means of material strength that had defined much of the past — had receded. The shared pursuit of economic prosperity signalled that people wanted Sony more than soil. It created a harmony of interests that, in the words of President William Jefferson Clinton, meant power politics “no longer computes”. Under the new overdog’s banner, peoples could come together and “problem solve” as technocrats. How convenient.

The manifestations of fundamental progressive change were, allegedly, obvious. There were treaties against land mines, nuclear test bans, the growth of a development-aid-nation-building network, the spread of a “norm” against conquest, the creation of enlightened statutes and benign transnational bodies such as the EU, and the rise of a global civil society.

Once, there had been the hope that class solidarity and a revolutionary proletariat would supplant interstate rivalries. That hope had withered with experience. But for many, a global liberal conscience had formed. Under the protective wing of a power that believed it saw further, the spread of democratic capitalism was rewiring the human spirit. Warning signs to the contrary, from the bloodletting in the Balkans to Africa’s great war in and around Congo, hardly shook the macro vision.

Even in the war on terror, the post 9/11 dystopian prophecies about a new disorder, the mating of extremism, terrorism, rogue regimes and WMD, were implicitly optimistic. Great power competition was a relic, as was Realpolitik. The future was one of money-making whilst policing the frontiers. Even a rising, wealthy, populous China with access to the sea would still, somehow not do what such states typically do and bid for dominance. It would genuflect to Washington’s ascendancy.

Alas, things change. International politics is both anarchic and fluid. The industrial revolutions of Asia are momentous. As is the breaking out of actual war — not hybrid, sub-threshold shadow wars but in-your-face industrial scale conflict, all of which focuses the mind for those close to the blade. True, since 1945 war fatalities may be down, historically, but build in the medical revolution and non-fatal casualties, and war remains frequent enough. Add in the fatigue of the status quo superpower against the hunger of its rivals. This all means there is a material shift afoot and a psychological one. History is not directional, it turns out, and does not arc towards light. It has returned to its default rhythm, the gunning for the upper hand, self-regard under pressure over other-regard, saying one thing and doing another.

The best paradigm that accounts for this world, or at least which provides foundations for seeing, is the one that sees the shadow of war as central, which looks at the globe without euphemism, and which prices in the fallenness of humans into its recommendations. Realists get things wrong at times. We find cases of virtue which are hard to explain, like Britain’s expensive suppression of the slave trade or South Africa’s nuclear disarmament. We don’t uniformly make correct point-predictions, like the timing of the Soviet Union’s fall. But as a “first cut” map of the world as it is, it is the least bad one.

❂

Three classic objections confront realists, all of which deserve an answer: that realism is immoral, un-realistic and parochial, only for white Euro-Atlantic elites.

Is realism immoral? No. It has an immoral cousin, amoral Machtpolitik, that craves power for its own sake. But realism offers a different kind of morality, reason of state. When the ruler acts, they do so on behalf of their polity, and its citizens, and therefore might do ruthless things unthinkable in private life, such as Winston Churchill’s sinking of the French Vichy Fleet in its ports. And they do so in a deadly environment of cheating, coercion and bad faith. As international relations cannot be croquet on the vicarage lawn, this is a morally serious enterprise.

Is realism realistic? Sure, rulers don’t always behave like Otto von Bismarck, disciplined, calculating utility-maximisers. But they tend towards self-seeking behaviour, especially when the chips are down, even when they’d prefer to practice gentler diplomacy. Even moments celebrated for solidarity, like the Concert of Europe, were more cut-throat in practice.

History suggests the wages of failing to self-help enough. 19th century China’s cultural glory could not prevent predation at the hands of European plunderers. The treasures of Baghdad, a medieval seat of learning under the Abbasid Caliphate, could not ward off the devastation of Hilegu’s Mongol army. The monks of Lindisfarne rejected violence in their dedication to the life to come. But the Vikings who laid their world to waste prayed to different gods.

How else to explain the abrogation of the Treaty of Ottawa, and its rejection of landmines, by East European states in the eye of the Russian imperial storm? How else to fathom why the three powers with the largest nuclear arsenals — Russia, the United States and China — are preparing the ground for the resumption of nuclear testing? Satellite images show “expansion and modernisation work” at test sites from the far western region of Xinjiang, the Arctic Ocean archipelago and the Nevada desert. How else to explain the widespread hedging of states with bloodstained Russia, whose traffic in arms, energy, commodities and technical expertise makes the “norm against conquest” inconvenient?

Benevolent aspirations for a better world exist, of course — the humanitarian impulses, the desire to escape the nuclear shadow, the desire to make everything about economics. But the test is not whether humans entertain noble aspirations, dreams of transformation or internationalist values. They do. The test is whether they stick to them when the heat rises and those cherished things become inconvenient.

Most of the time, they prove flexible. When survival is threatened, organised societies revert to the primacy of their own security, understood in adversarial terms, whilst their codes fall away like luxuries. Liberal norms looked powerful once. We can all be high-minded during the good times.

Is realism parochial, really just the local and culturally-specific behaviour of Euro-Atlantic states and their power-balancing games? Some say it is, arguing that other “strategic cultures” in the Middle East, Africa or Asia lean towards a statecraft more hierarchical, or more oriented to sub and trans-state fidelities, or more religious.

Be wary of such claims. Historically, there are oceans of realist practice to be found in India or China. Iran may declare a spiritual prohibition on nuclear arms, but it keeps for itself a doctrine of expediency in defence of the republic. If powers will be powers, Tehran keeps a free hand to do what it likes.

Likewise, tell a story about China’s historic rejection of imperialism to Cambodians, Vietnamese, Koreans, or indeed the displaced peoples whose real estate was taken for the sake of the Great Wall. Post-colonial African rulers, as Errol Henderson demonstrates, practised competitive power politics by sponsoring insurgents across borders, realism recast in “neo-patrimonial” form. India may repudiate the legacy of empire and claim to embody a morally-derived form of diplomacy. But now that it is richer and more ambitious, it carries out extrajudicial assassinations and tightens its control of Kashmir. We are a long way from Gandhi.

Neither is realism gender-specific: the closest society to matriarchy thus far, the Iroquois Confederacy, built an empire. Indeed there is irony in insisting realism is only for white, male, Western, Atlantic people. Who is being parochial, exactly?

Realism, the acceptance of these realities, tries to be coldly clinical. But at its most conscientious, it has a noble purpose. Realism prescribes Realpolitik not to maximise power and ensure biological life for its own sake, but to secure the things the polity cherishes: Kurdish women battling to resist ISIL slavery; Toussaint L’ouverture, quoting Machiavelli, by turns fighting and bargaining with colonial powers to free Saint-Domingue; and Machiavelli himself, who ended his pitilessly hard-nosed instruction manual The Prince with a plea for his patron to unite Florence and Italy under one banner. Adroit minds with civic hearts. There are worse places to start.