This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

The Englishman’s Room — that enchanting, unlikely, much-imitated yet never equalled classic of interior design books — turns 40 next year. Even more so than with most of what happened in 1986, it would be impossible to replicate today. The idea behind it was simple. Thirty-one men — and they were all men, unabashedly and unproblematically so — each chose a room that was close to their hearts. Prompted by a questionnaire, they wrote a brief essay about it. The rooms and their proponents were photographed. The result, once edited, topped with an introductory essay and tailed with biographical précis, was laid out in a way that awarded each subject two or three pages, plus three photos at the very most. Like most books in the 1980s that required accurate offset photolithography, The Englishman’s Room was printed in Italy. Published by Penguin, it was released concurrently in the UK and US in September 1986. The book proved a commercial success, unwrapped to expressions of unfeigned delight that winter under countless Christmas trees, more or less tastefully decorated, in every corner of the world where English style, and all that underpins it, is acknowledged and admired.

❋

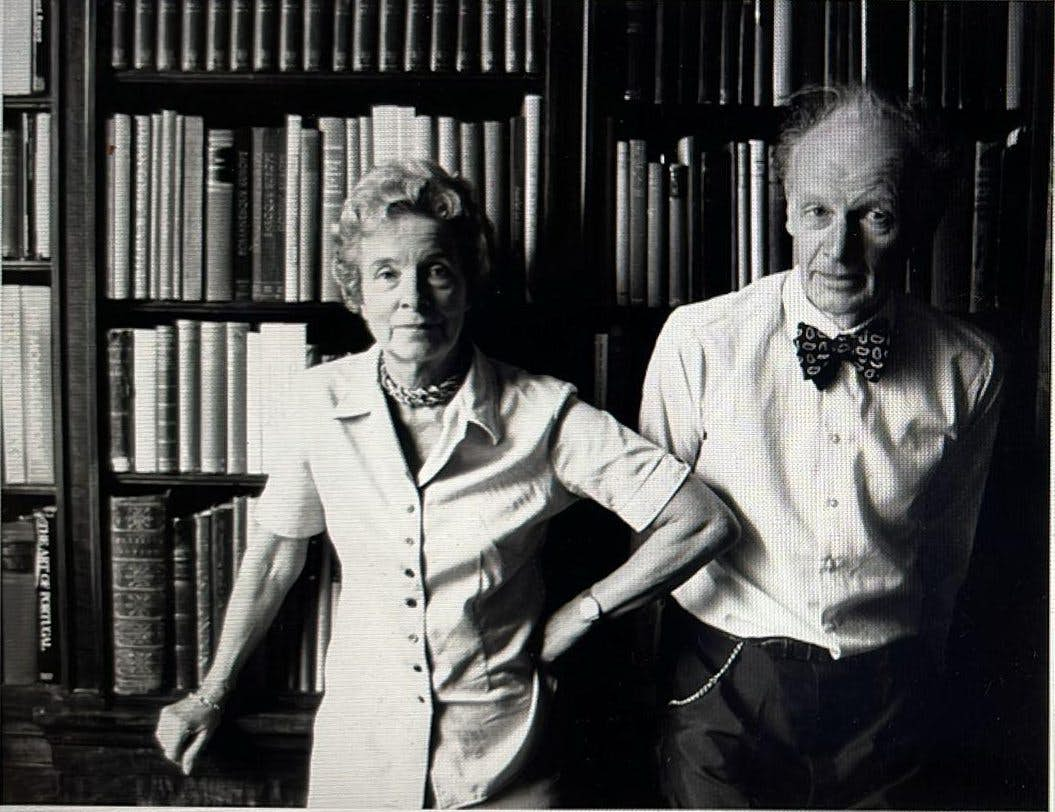

The concept behind The Englishman’s Room wasn’t, even in 1986, particularly new. The original scheme was hatched by children’s book publisher Sebastian Walker, whose eye for visual impact was equalled only by the shrewdness of his commercial nous. According to Michael Bloch, Walker suggested to Alvilde Lees-Milne (1909–94) — socialite, Francophile, amateur garden designer and wife of architectural historian and waspish diarist James Lees-Milne (1908–97) — that there was scope for a book, gorgeously illustrated, in which an assortment of women wrote, briefly, about gardens they had made.

The result, co-edited with Rosemary Verey, was The Englishwoman’s Garden (1980) — followed by The Englishman’s Garden (1982), then by The Englishwoman’s House (1984). Alvilde, already in her 70s, now presided over a successful publishing formula. The fact that she was, as Bloch put it, never “much of a reader, let alone a writer” proved no impediment.

What Alvilde Lees-Milne had, which mattered much more, was a stellar list of contacts, the bossiness required to bring them to heel and — related to her qualities as a garden designer — a confident eye for juxtapositions, contrasts and happy accidents.

With a different editor, The Englishman’s Room might have been a more ordinary book. Alvilde’s father, a swashbuckling army officer, governed South Australia from 1922–27, which may explain why, of the 31 Englishmen included in the text, ten write about foreign rooms. Here was an Englishness by no means contingent on geography.

In her teens, Alvilde was sexually abused by her father. Blithely bisexual — her first marriage was enlivened by an affair with Princess Edmond de Polignac (née Winaretta Singer), heiress to the American sewing machine fortune — she preferred the company of women and gay men. This, too, left its mark on The Englishman’s Room, where there’s fun to be had in trying to work out exactly how many of the participants are likely to have been to bed with one another. (Hint: making a diagram helps.)

Alvilde was also, crucially, a woman of sophisticated, often terrifyingly categorical good taste. To the extent she was a snob, it was through these channels that her snobbery ran, rather than across the pages of Burke’s Peerage.

The selection of contributors to The Englishman’s Room is at once so eclectic and so coherent, so eccentric yet seemingly inevitable, that it can only have been a deeply personal one, based on Alvilde’s conviction not only that her own taste was flawless, but that these disparate men, spread amongst Italian villas, crumbling inherited piles, minor country houses and rented London flats, somehow shared and exemplified it.

❋

Because the potted biographies of the 31 Englishmen are hidden away at the end of the book, the effect is like turning up at a star-studded, nightmare-inducing drinks party where everyone not only seems to know everyone else, but where one is expected to know everyone, too. No concessions are made, as they would be made now, to “accessibility”. This is sink-or-swim territory. Yet after a disarming confidence or two, one slips into the conviction that one is part of the charmed circle.

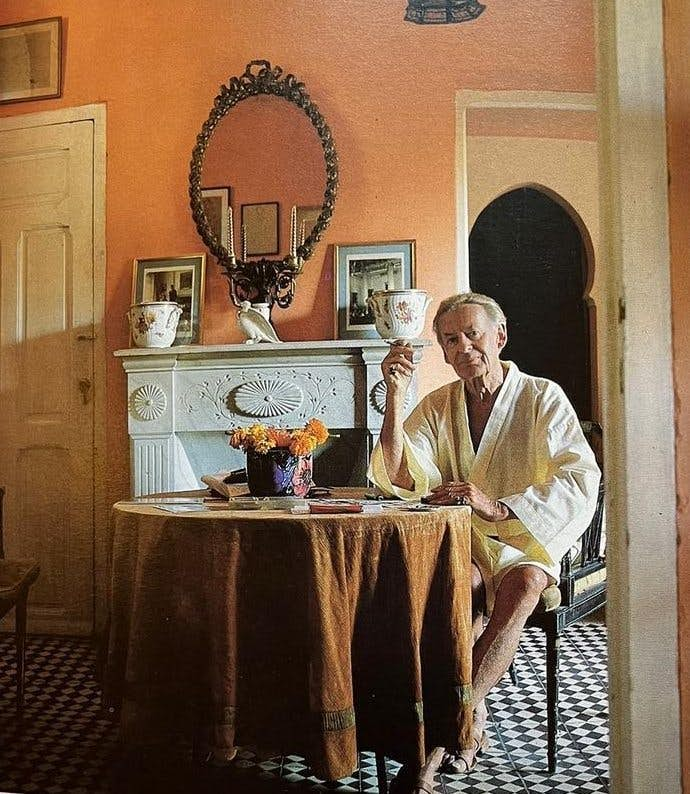

So it is that the Hon. David Herbert, clad only in an alarmingly short dressing gown and writing from Morocco, can allude to the inconveniences of a childhood spent at Wilton — it is assumed, naturally, that we all know “Wilton” — before veering off-piste to talk about cats. When the improbably handsome young Stephen Blow, plimsole-clad foot delicately propped on the arm of his chair, opines that “talking to people can be very tiring and frequently, alas, a disappointment”, we wish only to comfort him — and to learn from his paint choices.

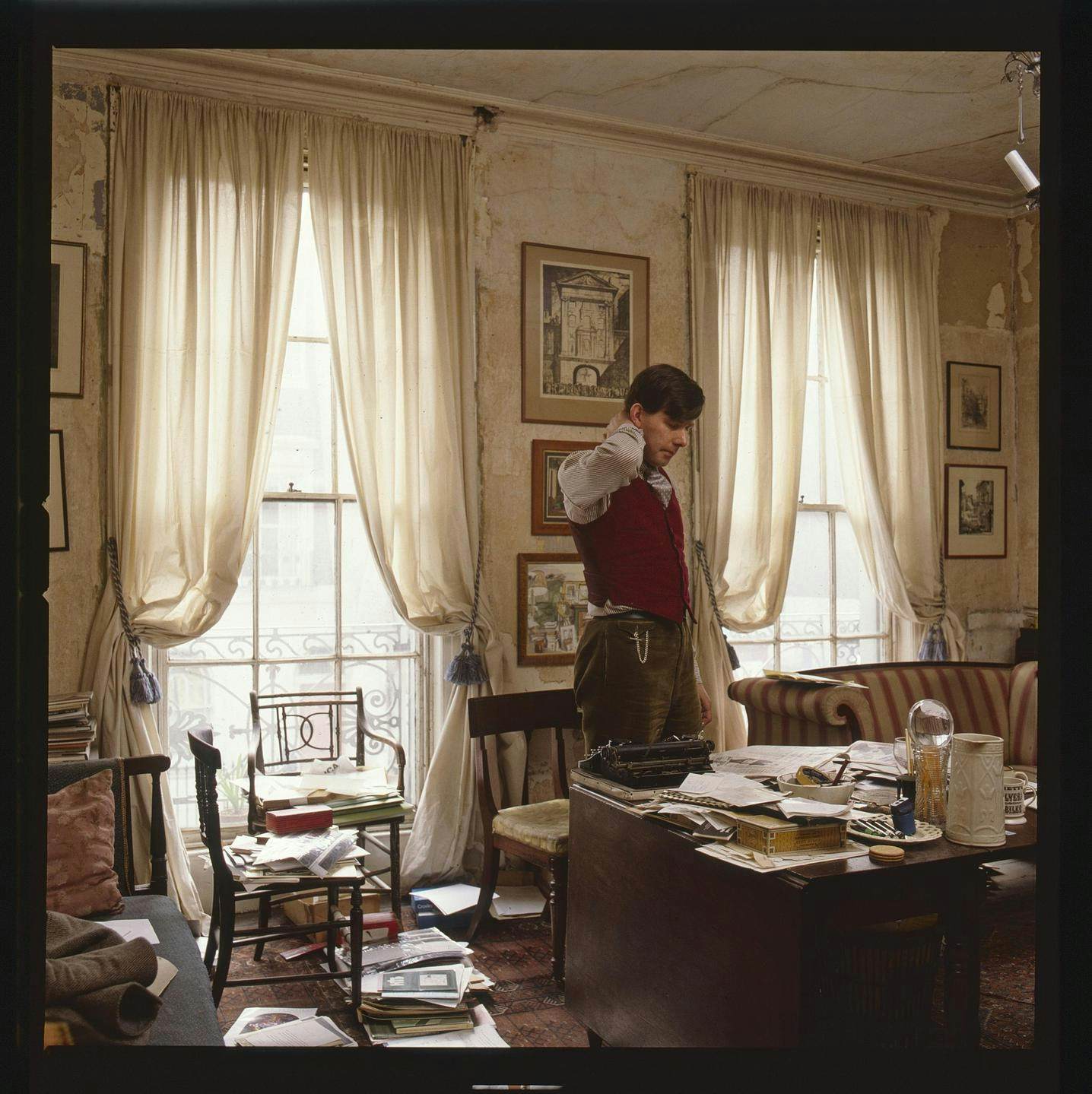

There are no Modernist interiors, no minimalism. Several participants — Dirk Bogarde, David Mlinaric — must have had a tidy-up and a delivery of fresh flowers on the day of the photo shoot. I suspect Gavin Stamp, however, of purposefully throwing his books and papers about, for rhetorical effect.

There are revealing asides. James Lees-Milne — yes, the husband of the editor — having discussed sharing a library with the ghost of William Beckford, confides, “On the whole, I prefer the dead to the living and things to people.”

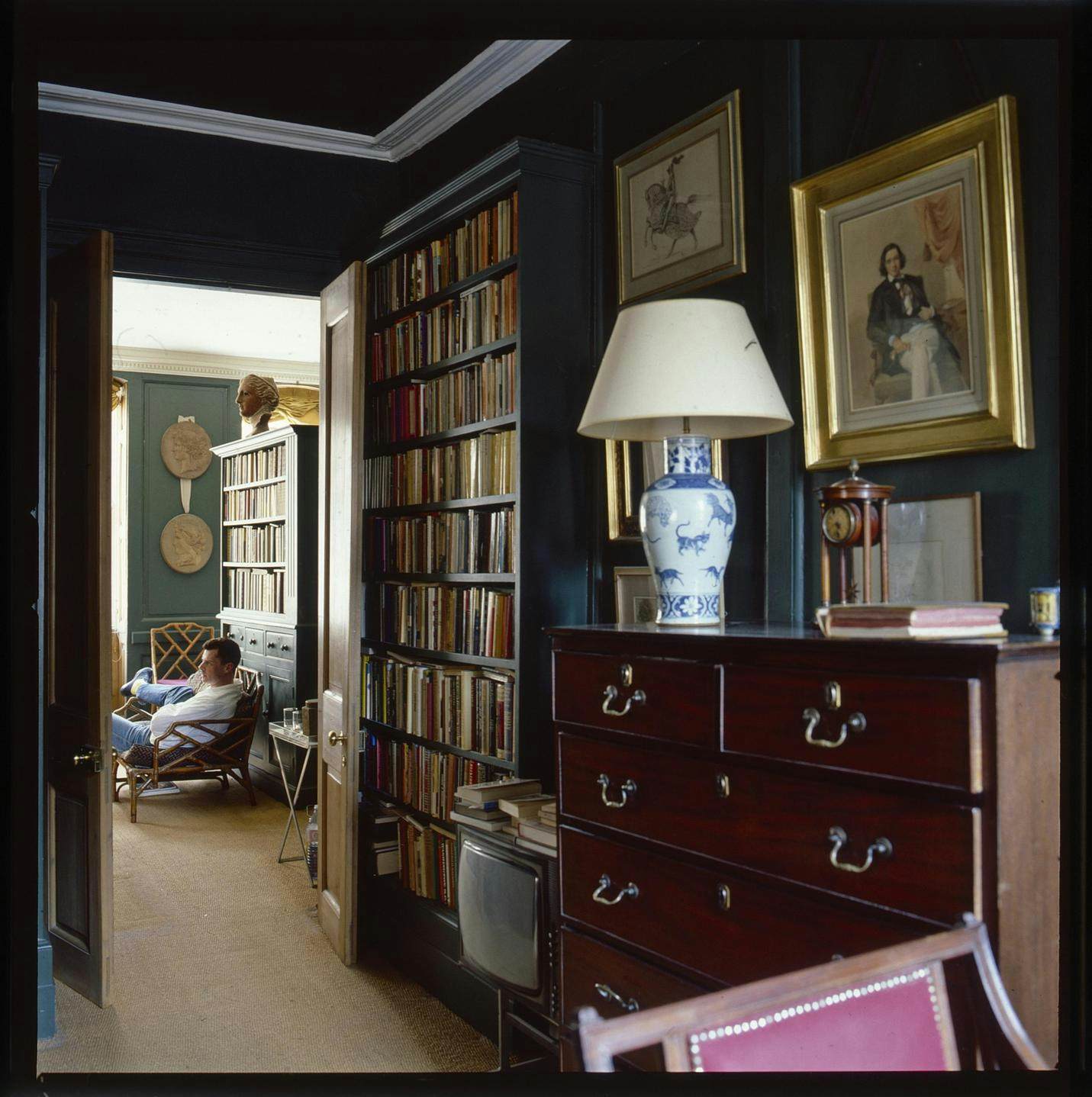

The 11th Duke of Devonshire dilates upon his book collection — “my particular joy is the disaster shelf” — before pronouncing, like a happy infant, “I love my room.” Meanwhile the Rt Hon J. Enoch Powell, MP, describes his 12-by-nine-foot space entirely in terms of its books, most of them erratically housed, to which he attributes elegiac sentiments.

But why, you might ask, is Enoch Powell — not conspicuously a style icon — featured in a book about interior design, alongside David Hicks, Sir John Gielgud, A.L. Rowse, Nigel Nicolson, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Hardie Amies and all the rest?

Such, though, is the enviable, uncompromising self-confidence of The Englishman’s Room. If you have to ask, you’ll probably never understand.

❋

The other key figure behind The Englishman’s Room was the photographer, Derry Moore (b. 1937), from 1989 the 12th Earl of Drogheda. As Jim and Alvilde Lees-Milne had, since the 1950s, usually spent Christmas with the 11th Earl of Drogheda and his family, the commission was a natural one.

Moore’s visual pedigree was extraordinary. First, he studied with Oskar Kokoschka at his so-called Schule des Sehens in Salzburg, painting watercolours in order to “learn how to see”. Later, he sought out Bill Brandt for photography tuition. Through experience with AD and The World of Interiors, Moore had, by 1985, perfected his own mode of portraiture, balancing formality with an inquisitive romanticism. His subjects frequently stare reflectively into the middle distance — evidence, incidentally, of lengthy, highly orchestrated poses.

It helped, of course, that Moore knew most of those involved in this project. They could relax around Moore — and so too, by implication, around us.

❋

Explaining a joke ruins it. Still, whilst there are splendid jokes knit into the fabric of The Englishman’s Room, it is, perhaps, worth unpicking one chapter, to grasp how the magic works. Let’s pause, then, over the essay devoted to Sir Nicholas Henderson, GCMG, KCVO, photographed in his home in the West Country.

Back in 1986, “Nicko”, as he was known, had achieved an unusual level of popular recognition by serving as ambassador to the USA from 1979–82, including during the Falklands War. Tall, urbane and well accustomed to performing Englishness before an international audience, he chose to frame his essay — which, unlike some contributions which maintain a suspicious homogeneity of tone, I’m convinced he wrote himself — in terms of a genial, mildly teasing dialogue with his editor, explaining the practicalities of his room.

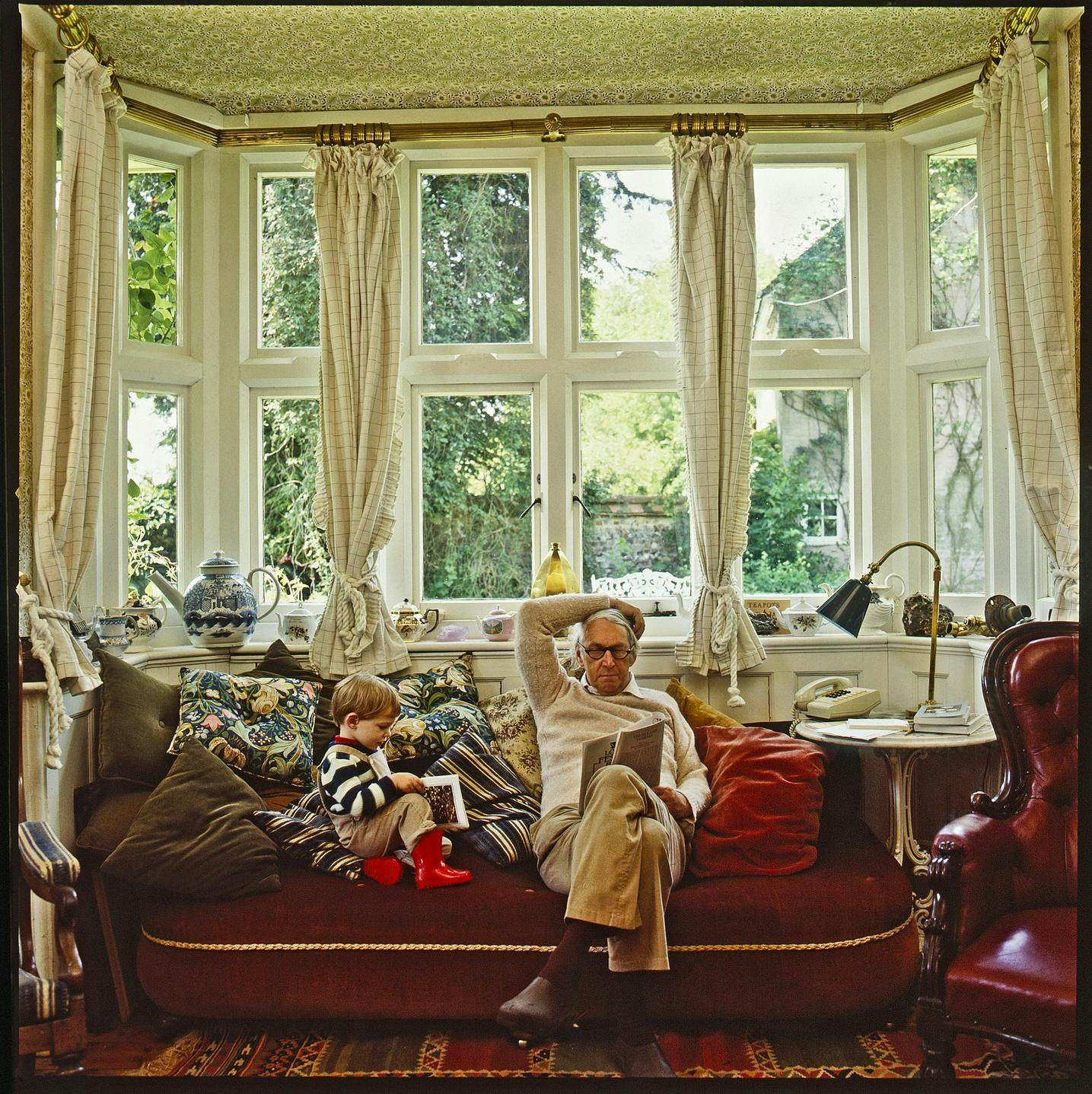

The main photo presents, at first glance, a consummately ordinary scene. An elderly man reclines on the squashiest, most cushion-strewn of sofas, perusing The Spectator, framed slightly off-centre against large alcove window overlooking a garden, the window stretching almost to the top of the image. Next to him on the sofa is a dear little boy, two or three years old, wearing red wellies, lost in a book.

Accessories include a telephone and a Christopher Wray table lamp. This, then, is no grand country house, filled with priceless antiques. Instead, we see only grandfather and grandson — silently companionable Englishmen — exemplifying comfort, continuity and the civilised pleasures of, as Nicko puts it, “doing nothing, intently and [almost] alone”. If all of this weren’t English enough, a number of teapots, varying in size and shape, punctuate the window ledge.

Yet there’s more to this artless scene than meets the eye. By this, I don’t just mean improbable cleanliness of those wellies, nor the way the artlessly scattered cushions are deployed so that the red one is on the right, echoing the wellies in a duller tone, whilst the William Morris cushions, also picking up that red, are piled up behind the toddler, not behind his grandpa.

Put bluntly, I feel certain that the curtains were moved from the more normal spot in the corners of the window to frame the two figures more effectively. Nor am I convinced that the large teapot on the left, only precariously balancing on the window ledge, is destined to remain there long, no matter how well-behaved the grandson in question might be.

Finally, there’s the question of light. Anyone who tries to photograph figures in front of a window in bright daylight, in a way that allows for clarity whilst avoiding deep shadows or distorted colours, will quickly discover how hard this really is. Creating the “effortless” scene before us surely entailed not only skilfully-placed artificial lighting, but probably also gel filters, perhaps also many other time-consuming technical tricks.

But how, we might ask, was the toddler persuaded to put up with all this fuss? Here, there’s an answer. It turns out that Nicko Henderson and his wife’s only child, a daughter, in fact married Derry Moore. Nicko’s grandson was born in 1983. So the air of affectionate familiarity captured in this scene — so crucial to the spirit of the English room — is, at least, absolutely genuine.

❋

Alvilde Lees-Milne died in 1994, but The Englishman’s Room went on to spawn plentiful offspring — a publishing genre in which the words “English” and “room” continue to be combined in ever more inventive iterations.

Of these, one of the best is Derry Moore’s own creation, The English Room (2013). Glossily illustrated, smartly produced, it was — as Moore acknowledged in his preface — a book for its own times, quite unlike its predecessor. Noting that his friend Alvilde Lees-Milne’s subjects “came from very much what might be called ‘her world’, mainly upper class and all sharing certain criteria of taste,” he went on to declare, starkly, “that world has now largely vanished”.

Moore’s solution, he explained, was to alter the format, adding women and young people and encouraging his participants to choose rooms that were significant to them, rather than ones in which they lived. What implications this might have for “certain criteria of taste” went unsaid.

The result is, at any rate, a very different book. There’s less text. The photos are larger, more abundant, but less rich in detail — not least, because there’s much less detail to convey. The essays explain how these rooms make their subjects feel — sidestepping all the incidental, practical, humanising detail of how the rooms are ordered or dressed, let alone the reality of living in them. The effect, then, is far less odd, eccentric, opinionated — but also less intimate, more guarded. No one talks about books left unshelved, cat trays, clutter, dust or the virtues of leaving things as they are.

❋

Most interior design books, these days, are exercises in brand-building. There’s nothing wrong with this. Who amongst us would be without the gorgeously-presented manifestos of the late Robert Kime, Ben Pentreath, Flora Soames or Retrouvius? But the contrast with The Englishman’s Room, with its horror of interiors that have been “arranged” (despite the participation of David Hicks and David Mlinaric) is striking.

There are reasons why the market in interior design books has taken this turn. Chief amongst these is the ever-accelerating proliferation of free online design content. Why publish a book when World of Interiors, the vibrant chaos of Instagram and, indeed, the prurient amusement of Rightmove.co.uk are a click or two away? Only as upmarket advertising does publication make sense.

The creators of The Englishman’s Room were, admittedly, hardly oblivious to commercial opportunities — not least, in the US market. From Nancy Mitford’s Noblesse Oblige (1956) to Mirabel Cecil’s invention of “shabby chic” in The New York Times (1979) and Granada Television’s Brideshead Revisited (1981) to the blockbuster Treasure Houses of Britain exhibition (1985), commentators have sought to explain the apparently effortless, unconsidered perfection of traditional English style to eager audiences, both abroad and at home.

❋

This sort of thing is never, however, as anodyne as it looks. Nor was this — in 1986, soon after the then Prince of Wales’s famous attack on the myopia of the mainstream architectural establishment — a simple case of tradition picking a fight with the worst sort of modernism, described by Roger Scruton as “an attempt to remake the world as though it contained nothing save atomic individuals, disinfected of the past and living like ants within their metallic and functional shells”, although this was surely part of the argument.

To describe how something has been done is, often, to mandate how it ought to be done. The close-knit circle in which The Englishman’s Room was created was, in the main, conservative — often with more than just a small “c” — yet simultaneously deeply unsettled by the degree of cultural change — Americanisation very much included — attendant on High Thatcherism. At RIBA, Prince Charles quoted Goethe’s dictum that there is nothing more dreadful than imagination without taste. The Englishman’s Room made the same point, albeit by showing rather than telling.

This was, and remains, urgent work. Researching a book on the Cotswolds in 1987, Jim Lees-Milne lamented “these fly-by-night, new rich, suburban-minded, totally non-country folk” who “tarted up” the properties they acquired, before moving on. “No one stays long. Each owner undoes what the previous one did. No owner leaves well alone.” Snobbery? Probably so. That doesn’t, however, invalidate its accuracy.

Forty years on, then, is The Englishman’s Room merely a period piece? I’d argue not, for two reasons. First, most of the interiors still look superb — a signal strength of this version of English style being that it improves with age. Secondly, though, the self-confidence of its contributors’ judgement has, perhaps more than ever, a message for us. We can still choose to live in a way that’s informed by inherited traditions, beauty, good taste — or, indeed, the opposite.