This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

It is a commonly accepted view that left-wing governments are friendlier towards the arts than those on the right. When giving talks about my new book on British operatic culture over the last century, I have been asked by audience members to confirm their assumption that the rot set in with Thatcher.

History, however, is almost never quite as neat as people would like. There have been periods, my research shows, when the Labour Party has been generous and encouraging towards the opera world and times when it has been distinctly hostile. The same goes for the Conservatives. We need to be equal opportunities critics when it comes to judging the two main British parties on their arts record.

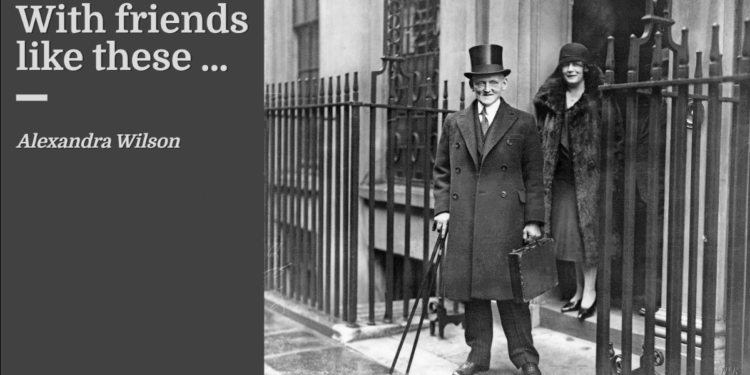

A century ago, with no state funding for the arts in Britain, politicians had little direct involvement. That all changed in 1930 when Labour Chancellor Philip Snowden proposed supporting opera at Covent Garden from public funds.

It was a case of “nice idea, terrible timing”. Subsidising opera struck many as a bizarre indulgence at a time of economic crisis and a concession to Snowden’s opera-loving wife, even though the government tried to make the patriotic case that the scheme would generate jobs. A media storm erupted about suitable use of taxpayers’ money and whether one should pay for activities one did not personally pursue. Opera had become a political hot potato.

Interestingly, objections to Snowden’s subsidy came from both sides of the House. Tory MPs put forward a motion opposing it “in light of the present economic situation”, asking why opera should be prioritised over cinema, Shakespeare, sugar beet production or orphans. Some Labour backbenchers were also unhappy. One hailed the scheme “a public scandal” and called for the money to be spent on allotments for the unemployed. Another objected to the use of public funds “for the purposes of boosting long-haired foreign artistes”.

The plan to subsidise opera was shelved. But it re-emerged after the Second World War to a much warmer reception when the Arts Council was established under Clement Attlee’s government. J. B. Priestley wrote in 1947 that now was the moment for the Left to make good on long-held pledges to stand up for art and artists.

The Arts Council soon came to be broadly accepted across the political spectrum, though there would be periodic objections from individual MPs, those on the right insisting the money could be better spent, and those on the left expressing concern about opera’s “luxuriousness” in the austerity years of the 1950s. Nevertheless, the annual subsidy to Covent Garden rose exponentially over that decade, with the Conservatives keen to see it increased yet further.

In the 1960s, meanwhile, Labour’s Jennie Lee, the UK’s first Minister for the Arts, almost trebled the Arts Council’s grant from £3.2 million in 1964–65 to £9.4 million in 1970–71. Lee saw no incompatibility between artistic excellence and access. She understood the long, noble tradition (now largely forgotten, but explored in detail in my book) of working-class opera-going and was keen to foster operatic activity beyond London. At the same time, her sympathetic attitude towards Covent Garden garnered her support amongst Tories.

As the pendulum swung back once more, the Conservatives lavished money on the arts under music-loving Ted Heath, an ever-greater proportion of Arts Council funding going to opera. Just as in the 1930s, this raised hackles at a time of economic strife, yet politicians persisted in speaking positively about the value of the arts. Lord Eccles, Conservative Minister for the Arts, was quoted in The Economist in 1972 as saying, “A nation is to be judged by the quality of life it maintains and that life-quality involves something more than a swelling torrent of cars, television sets and dishwashing machines.” Later in the decade, now in opposition, Conservative MPs formed the Opera and Ballet Policy Group, which called for yet further increases in funding and posited itself as friendlier to the idea of opera for the people than Labour.

A change of tone was afoot in the 1980s, however, and most people in the opera world swiftly concluded that Margaret Thatcher was very much not their friend, though she did occasionally put in an appearance at the opera.

There was a growing feeling on the right that the arts should be able to hold their own in the marketplace, with William Rees-Mogg, at the helm of the Arts Council, arguing that “subsidy creates dependence”. These were certainly difficult years for the arts, and a growing scepticism about arts subsidy coincided with the press (particularly Rupert Murdoch’s stable) beginning to disseminate the stereotype that opera was “elitist”, despite the fact that it was wildly popular at the time and firmly integrated into popular culture. Artists, including opera singers, found themselves mocked as “luvvies”.

But parts of the Left were no more helpful. Some Labour politicians supported subsidy in principle, but had a blind spot for opera. In 1984, Edinburgh’s new Labour council proposed removing subsidy from the Edinburgh International Festival and scrapped plans to replace the cramped King’s Theatre with a new opera venue. The Guardian reported the council was “widely believed to have been elected because of its doorstep promise not to build the city’s long awaited opera house”.

In London, meanwhile, Tony Banks, the chair of the Arts Committee of the Greater London Council, recommended — to widespread outcry — reneging on previous pledges to fund Covent Garden and ENO, suggesting the money be diverted to community arts and football instead.

As the son of a music hall artist, John Major was more naturally inclined to favour the arts than Thatcher. He struggled to convince his colleagues but had an ally in David Mellor, who bought the London Coliseum for the nation, saying, “For me, the chance to guarantee great opera at affordable prices in the heart of London was irresistible.”

By the mid 1990s however, opera had become political dynamite, as the now mismanaged Royal Opera House became mired in controversy, the result of a massive Lottery grant that stoked tabloid ire. The public mood was far from friendly.

Hopes were agonisingly high in the arts world that New Labour would be the answer to its prayers, but disillusionment set in swiftly. As Sir Peter Hall lamented in The Spectator in 1998: “Thatcher did not believe in supporting the arts. She thought subsidies distorted the market and encouraged the lefties. She was unimpressed by the huge achievements, and even by the huge earnings from tourism. New Labour is now busily adopting the same attitudes, though with different explanations … To the Right, originality produces left-wing dogma; to the left it spells dangerous elitism.”

In some ways, New Labour placed the arts front and centre: gains included a boom in filmmaking and free admission to national museums. But certain forms of culture were favoured. There was much championing of the applied arts — fashion and design, radio and TV production, film and animation — and as Hugo Young wrote in The Guardian, “The entire thrust of [Blair’s] Government’s political strategy requires it to be seen with Noel Gallagher.”

But opera occupied an uneasy place in “Cool Britannia”, and there was talk of privatising Covent Garden. As the arts manager Peter Jonas, who had recently moved from ENO to the Bavarian State Opera, wrote in Opera magazine in 1998, Britain had “a crisis of political and social confidence in opera … Money cannot be the problem in a country where £758 million is to be spent on Mandelson’s Dome”.

Blair’s Culture Secretary, Chris Smith, posited himself as the champion of a “people’s opera” but talked repeatedly about how elitist opera had been, reinforcing misleading stereotypes in the mind of the public. This sort of talk had practical consequences: patrons became increasingly fearful of being seen to be supporting “elitist” art forms. The Midland Bank, for instance, abandoned its longstanding sponsorship of the Covent Garden Midland Bank Proms, which had allowed people to watch performances at extremely low cost.

By the 21st century, politicians on both sides of the House seemed to be interested in the arts only when it gave them an opportunity to talk about “access” or “the creative industries”, again fuelling clichés about classical music’s supposed associations with privilege. In 2008, Margaret Hodge attacked the Proms, of all things, for not being a festival where people from different backgrounds could “feel at ease”.

New Labour politicians were rarely spotted at theatres or galleries unless on official business, though were often seen at sporting events. The same applied to their Tory successors: performative “ordinariness” was regarded as a better vote-winner than admitting to an interest in “elitist” opera.

Today opera is under attack both by a populist right that disparages it as a trivial luxury for “metropolitan elites” and a left so concerned about cultural relativism and “privilege” that it cannot bring itself to defend the so-called high arts.

Brexit had serious consequences for opera, particularly for singers, who by the 2010s were operating in a global industry that required freedom of movement. The pandemic brought another crisis in terms of finances and practicalities, and the opera world became embroiled in a culture war as politicians argued about what entertainment forms to prioritise as the world opened up again.

The editor of Opera magazine wrote in 2019, “Changing political regimes have of course brought changed priorities — John Major’s idea of culture was ‘heritage’, Tony Blair’s ‘Cool Britannia’ — but the present hopefuls seem to have no notion of culture at all.” Certainly, by the 2020s, as both main parties courted the red wall, neither had much time for the arts.

Arts Council England’s 2022 redistribution of funding, at the behest of Nadine Dorries, inflicted major cuts on British opera, and its insistence that ENO relocate to Manchester has created great uncertainty for the company’s chorus, orchestra and staff. Some Tory backbenchers were aghast, Sir Bob Neill saying in a Parliamentary debate, “We need a proper strategy for opera. Opera is a major part of the British music scene.”

Hopes that Labour would race in on its white charger to save the arts in 2024 were, predictably, soon dashed. Lisa Nandy gave a speech in which she included opera in a list of art forms that are “the building blocks of our cultural life, indispensable to the life of a nation, always, but especially now”, yet the opera world has so far seen little positive change. A £270m funding package for the arts, culture, libraries and heritage sector offered welcome support for theatre infrastructure projects, but a funding award to the creative industries had nothing to say about opera. Meanwhile, ENO’s future remains uncertain, and the Welsh National Opera is in real jeopardy. Intervention is desperately needed.

Arts funding will always be regarded as a low priority in hard times, but politicians also exercise influence over public opinion in the ways they talk about the arts. Lately, both parties have done considerable damage to opera’s cause by stoking the harmful elitism stereotype and by valuing the arts for “impact” rather than excellence. When it comes to assessing the relationship between politicians and the arts, then, we have to be even-handed both in our approbation and condemnation. When they set their minds to it, Labour and Conservative politicians alike have shown that they can give the arts sector, and opera in particular, a real boost. Unfortunately, they have also shown that they can create a hell of a mess.