Wagner’s last opera — his last word in theatre, which had an immense influence on pretty much the whole of European culture after its 1882 appearance — is filled with ritual, a characteristic seized on by the German director Susanne Kennedy, who wants to turn the whole five-hour show into a kind of re-enactment of the mythology binding the society performing and witnessing it. At least that seems to be the plan. The director, who always as here works with the artist Markus Selg, is well known in Germany and continental Europe (and as far as I know completely unknown here in our stubbornly non-European theatre world) for these mythic pageants, delivered with a determined sensory overload of constant video imagery and stage-cramming design events, and you can see why Opera Vlaanderen (Flanders Opera) boss Jan Vandenhouwe thought she might do something interesting with Parsifal.

This is a piece which (among its other immodest aims) seeks to redeem the Christianity it parodies from the parade of empty gesture and ritual Wagner insists it has become — well, actually to redeem humanity wholesale through a true understanding of reality and the meaning of compassion. It can be tackled in a thousand ways, but at some point they all need to come to grips with the implications of Wagner’s self-written words, evidently composed in a sort of fever-dream, delving into highly tendentious — not to say frankly iffy — subconscious-born imagery and discourse.

The central point, the long Act 2 duet between the not very holy “holy fool” Parsifal and the “wild woman” Kundry — a mishmash of archetypes who recalls most of all the legendary (rather than textual) Magdalene — happens where she, standing in for his dead mother, bestows a most unmotherly, hot kiss on the boy which, like a thunderbolt, reveals to him the meaning of suffering, love, life and everything else, which he proceeds to dilate on in some pretty wild imagery. For example: Kundry’s keen to take things further, but Parsifal, disgusted and repelled (though not really because of the mum thing), equates her “fount of sorrow” (by which he appears to mean the organ she employs to seduce and corrupt the Grail Knights) with the spear-wound that was inflicted on the Knight Amfortas during such a dalliance, telling her that for her to be redeemed, this unfortunate physical characteristic needs to be “sealed over”… This is quite a way from the earlier Wagner, so passionately sure that his (and therefore all human) redemption started and probably ended with sex. But hey, now he was pushing seventy, so maybe his libido was on the blink or wane.

Let’s go back a bit. The surface of Parsifal is deceptively familiar, with its Arthurian cast of Sir Perceval, Sir Gawain, the Fisher King, the Grail. But Wagner delights in making all strange and sickly. The gloomily chaste knights preserve the holy relics and go through the motions of rites that have become meaningless, while a renegade member, Klingsor, doggedly undoes them one by one in his handily situated whorehouse. During one such unfortunate episode Amfortas has lost Longinus’s spear to Klingsor and has been mortally wounded with it — a wound that festers disgustingly throughout the opera’s five hours.

Only an innocent, a holy fool, can cure him. Enter Parsifal, who is shown the mysteries but fails to understand. Finding himself later among Klingsor’s filles de joie, and spurning them, he meets Kundry, suddenly gets the message, understands Amfortas’s suffering, grabs the lost spear and returns (after a bit) to sort everything out.

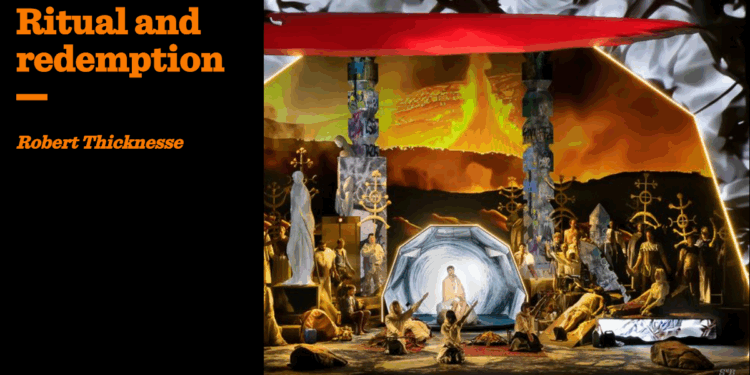

Apologies for all this but it feels basically impossible to review a performance of Parsifal without relating the story, which comes over so differently in every telling. As noted, there is not much “telling” here, and this is where the staging begins to basically avoid the issue of Parsifal. In the nature of ritual, people are essentially not conversing but reciting their lines: so there is no need for any of the usual theatrical interaction (or “acting” as it’s known) between characters. All is static, stately, hieratic: even the excellent Gurnemanz (Albert Dohmen), the knight who fills us in on most of the story (and the recognisable human who is our portal into the piece), declaims rather than sings. A gang of acolytes/adepts sit around doing not very much beyond making priestly hand gestures. The stage is surrounded by those projections of constantly changing landscapes, skies, thorny tunnels, sometimes with flickery CGI animals thrown in — a frame you quickly elect to ignore as much as possible. Parsifal (Christopher Sokolowski) himself is omnipresent in a kind of bijou lunar module with its own kaleidoscopic video stuff going on. Sometimes he floats in it, a hologrammatic Buddha. But mostly he sits on a rock and stares at the goings on around him in understandable bewilderment. What are these people up to and why? What are they waiting for?

That all makes the first act somewhat gruelling — not unusual, in my experience, as the ponderous setup unfolds. Act 2 doesn’t offer the usual visual release, essentially taking place in the same cave as the first, with the devotees now impersonating Klingsor’s flower-maidens rather languorously (there’s no attempt to be sexy, of course, perhaps a relief). And then things really kick off, as mentioned, with Kundry and Parsifal’s duet. And at this point, the music takes over, finally subsumes the repetitive and unilluminating, more-is-less mime-show mise-en-scène, and turns everything to magic.

The experience is really all that counts

That’s a well-known Wagnerian experience: the music in a unique way being the message and the meaning assumes a radiance and freightedness that blows away the crazed imagery of seeping blood, suppurating wounds, impure sex, incest, self-castration the rest of it, or elevates it into something else entirely, a vision of redemption that — being expressed in music — cannot be reduced to words or hardly even to mental concepts. A lot can and has been written about this, not all of it worthless. But the experience is really all that counts; I’m not saying it can actually do more than drown you in a wild excess and variety of sensual delights, despite its pretensions, but you can pretty much rely on it to work every time. The staging’s biggest fail actually comes at the end, the numinous lift-off where the mysteries are enacted and the Grail revealed in its essential form, but it really doesn’t matter by this point: the thing has become an entirely musical experience.

And that, naturally, doesn’t do itself: it’s always a massive technical and artistic achievement by an orchestra, conducted here by Alejo Pérez, the outgoing music director, whose pacing and control especially in the second half creates some pretty transcendent stuff, Wagner’s undreamed-of transformations and endless music evolutions thrillingly produced in a way that leaves you helplessly in thrall. Dshamilja Keiser is a more than usually mysterious but still hypnotic Kundry, Werner Van Mechelen a strong Klingsor, Kartal Karagedik provides the most beautiful singing as languishing Amfortas. The most astonishing thing of all is the fresh-faced young American tenor Christopher Sokolowski who stepped in to learn this monster role in a mere three weeks when the previous Parsifal withdrew belatedly — a hero who actually looks the part. It’s a magnificent voice, quite baritonal in timbre but still radiant up top, which will surely develop into something extraordinary. And he holds the stage in his immobility and obvious sense of human connection. He, Kundry and Gurnemanz hold this Catherine wheel of a show together, when it might otherwise quite easily spin off into outer space.