Two deadly attacks last weekend – both allegedly launched by decorated U.S. combat veterans – are renewing concerns about whether disaffected or radicalized veterans pose a unique threat to the country. The events also suggest that current efforts to reintegrate some soldiers into civilian life might not be sufficient, or effective.

Last Sunday, in Michigan, police said a former Marine driving a pickup with an Iraq War veteran license plate and flying two American flags rammed his truck into a church and attacked members with an assault rifle. They added that he then set the church on fire before being killed by law enforcement. The day before, in Southport, North Carolina, a Purple Heart recipient driving a skiff pulled up to a dockside eatery and opened fire, the police said. The man, captured by the Coast Guard, now faces murder charges. Seven people died in the two incidents.

Neither veteran status nor mental health problems are necessarily a predictor of violence. Yet, between 1990 and 2022, about a quarter of mass-shooting plots in the United States – where an attacker meant to kill at least four people – have been planned by veterans, according to research from the University of Maryland. Veterans, meanwhile, make up about 6% of the general population.

Why We Wrote This

Two recent mass-shooting suspects are decorated U.S. combat veterans. The events renew concerns about how America cares for veterans – including in regard to mental health care and meaningful social connections.

“When these things happen, they are catastrophic,” says retired U.S. Army Col. Carl Castro, co-author of “Boys in the Barracks.” “The impact is huge.”

The most recent attacks, unrelated but occurring less than 24 hours apart, added to a year of such incidents that began on New Year’s Day when a truck driven by an Army soldier exploded in Las Vegas in an apparent suicide. That same day, an Army veteran fatally wounded 14 people and injured dozens of others after using his truck to plow into a crowd on Bourbon Street in New Orleans.

This summer, a soldier at Fort Stewart, about 40 miles west of Savannah, Georgia, shot and injured five soldiers before being subdued and arrested.

Veterans’ skills with weapons and tactics can make such attacks particularly deadly. While many mass shooters have learned to use weapons outside of the armed services, several of the deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history were perpetrated by men with military experience, according to military studies.

Addressing mental health challenges

A willingness to address veterans’ mental and emotional health has long been challenging in a nation where soldiers are meant to embody strength, valor, and courage. Battle trauma can linger and reemerge years later, triggered by an unforeseen event or circumstance, experts say. And for many American veterans, their post-military careers can be dogged by poor decisions and adverse life events, such as divorce and job loss, says Colonel Castro.

This arc from honorable service to dangerous decisions – resulting at the extreme end in rare acts of mass violence – underscores the need for better mental health care and meaningful social connections once out of uniform, veterans say.

The suspects in last weekend’s attacks “served in the thick of it,” says Luke Baumgartner, an Army veteran and researcher on extremist violence at George Washington University.

“They both deployed to Iraq, and they likely were in some of the harshest sort of conditions during that entire fiasco,’’ he adds. “As a country, we’re still grappling with trying to figure out how to address the issues that these people will face when they come home.”

The U.S. was unprepared for the social and emotional costs of its post-9/11 military engagements and has taken years to address the plight of returning soldiers. But there has been some progress. These days, says Mr. Baumgartner, scores of government and nonprofit-supported rehabilitation and reentry programs offer veterans help to reintegrate into civilian life.

Still, the system can fall woefully short. Among elite forces, especially, admitting to mental health challenges could risk deployments and promotions, former officers say. In addition, access to veterans’ health services can be cut off if the soldiers leave with anything but an honorable discharge.

“Mental health problems may lead to things that get soldiers in trouble,” says former Army helicopter pilot Eric Carpenter. “So, some people who might need help are the ones getting cut off.”

Recognizing needs and seeking help

What’s more, research shows that radicalization can come long after individuals leave the military. The alleged perpetrators from last weekend’s attacks had both been out of the military for about 15 years. Vulnerabilities during the transition to civilian life – such as disconnection or bitterness – can make former soldiers more susceptible to extremist ideas and poor decision-making, experts say.

“There’s a lot of things that can get in the way of people getting help, or even recognizing that they need help,” says Colonel Castro, the director of military and veterans programs at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles.

“In many cases, military experience is the most important thing they will ever do in their entire life. And they are 19 or 20 years old when that happens. Think about the psychology of that: You’ve got another 60 years to go. That can wear on you, and not always in a conscious way.”

What veterans miss most about their time in the service is not the physical exercise or routines, says Mr. Baumgartner from George Washington University. It’s the camaraderie. “People are trying to fill the void,” he says.

That void, he adds, is where “you can form your own grievance and shape your own narratives to suit whatever thing you’re sort of [angry about] in the moment. It doesn’t have to be politically, ideologically, or religiously motivated in the traditional sense.”

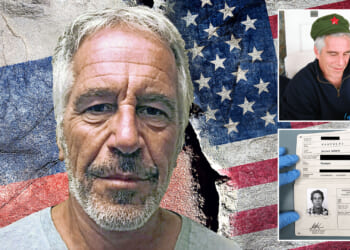

The Marine Corps confirmed that Thomas Jacob Sanford, the suspected shooter in Michigan, served a four-year enlistment as an automotive mechanic and deployed to Iraq for nine months in August 2007. His awards included the Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal, the Iraq Campaign Medal, and the National Defense Service Medal.

The Trump administration said the attack was motivated by hatred toward the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. One news report suggested that the man had been criticized by church members who disapproved of his tattoos.

Nigel Edge, the suspected North Carolina shooter, served under the name Sean William DeBevoise, reaching the rank of sergeant. Among his numerous awards is the Purple Heart, awarded to those who sustain injuries in combat. His last duty was with Wounded Warrior Battalion East at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.

When awards represent hardships endured

Understanding how decorated soldiers – who have often experienced significant battle-related stress – think about violence might be a good starting point in thwarting mass shootings, according to Salem State University sociologist Christopher Collins.

Mr. Edge, the alleged North Carolina gunman, left a long public record of his struggles. According to a 2007 article in the Wilmington Star-News, he suffered a traumatic brain injury from which it took years to recover. In the intro to his self-published book, “Headshot: Betrayal of a Nation (Truth Hurts),” he claims that the toughest part of the recovery was that “all of this was at the hand of friendly fire that would provide the most crippling mental damage.”

According to Mr. Carpenter, now a military law professor at Florida International University, the military retains some control over access to weapons, especially by enlisted soldiers on base.

But there’s only so much the military can do to keep weapons away from soldiers, even if they are exhibiting signs of trouble. Personal weapons aren’t allowed on bases without a commander’s permission, so if an enlisted person is showing signs of distress or about to hurt someone, a commander can call them onto base to separate them from their weapon. Off the base, soldiers have Second Amendment rights just like anyone else.

Professor Carpenter says that the Sutherland Springs church shooting in Texas in 2017 showed lapses in the military’s reporting of a court-martial to civilian authorities, which would have barred the suspect from getting a gun.

Before a reserve soldier killed 18 people in Lewiston, Maine, in 2023, the commander of his unit had tried to get him help. When military officials contacted authorities about their concerns, the civilian deputy sheriff who responded did not file a red-flag petition to have the guns removed from his house after determining the reservist didn’t pose a risk to the community.

The shootings this past weekend underscore, for some experts, that soldiers can represent the best and worst in American society, says Colonel Castro. But civilians, he says, have a broader responsibility to help integrate them.