Having taken a statesmanlike fortnight to consider the matter of the “Unite the Kingdom” rally organised by Tommy Robinson on 13th September, Sir Keir Starmer has now issued a solemn warning to the nation. “You don’t have to be a great historian to know where that kind of poison ends up,” he said. Those unsure of what the prime minister was referring to might try Googling 1930s Germany.

As the shadow of the Second World War begins to recede beyond the horizon of living memory, it seems destined to live on as a blunt political object. In every nation touched by the war, its memory served as a bedrock for the moral and political legitimacy of the postwar order. But it used to do so as a common national experience through which everyone had lived, or through which their parents had lived, even if in some countries it wasn’t always a unifying memory. Now, as time has gone on, it has come to assume a more abstract quality — far less visceral. It is now easier to distil into uncomplicated political “lessons” for subsequent generations.

At first, this seems a departure from what normally happens with the historical memory of war once those who fought through them, or who remember those who fought through them are gone. Normally, these historical conflicts are stripped of the beliefs and antagonisms that created them, or that were created by them, and are relegated into the drier and more objective fields of military and political history. But the popular memory of the Second World War, insofar as it is thought to contain moral lessons for the modern world, isn’t really about the conflict at all. It is about the circumstance that saw the Nazi Party assume power in Germany — and then the Holocaust which took place simultaneously to the fighting.

The simplistic “lesson” regarding the rise of the Nazis that my own generation of schoolchildren were expected to come away with was that it could have happened anywhere. That the incipient urge to follow a charismatic tyrant lurks just beneath the surface of every society, and that only by maintaining vigilance and by resisting any departure from formalism and due process could we avoid it. The spectre of hyperinflation in Weimar Germany stood in here for the kind of routine economic malaise that would weaken any society’s immune system and make them vulnerable to the hysterical hunt for a scapegoat.

Germany itself was completely de-specificised in all of this, as was the unique historical moment of the First World War and its aftermath. The idea among at least some of the wartime generation that there might have been something a bit off about the Germans, and that the totality with which they demanded war was symptomatic of a peculiar moral trait or failing, became politically inconvenient at some point in the 1950s. It could have happened anywhere; it could have happened here — and, critically; it could still happen here, if we let our guard down.

This sat uneasily with another liberal shibboleth — this one far more grounded in truth — about the nature of Nazism, which was its decidedly specific focus on the Jews as an enemy to be eradicated; both in rhetoric and in policy. If it could have happened anywhere, then surely one minority group is as good as another? It is difficult to insist on both propositions without suggesting that it is the presence of Jews in a society that brings out the beast in a nation.

The “it could happen anywhere” thesis of Nazism, and the corresponding call for eternal vigilance against incipient fascism, have led to the retrospective engineering of an ahistorical narrative about the rise of Hitler, and Germany’s road to industrialised genocide. In simple terms, this narrative holds that the Nazis assumed power in a piecemeal fashion, and that they were initially coy about their intentions toward the Jews, and about their totalitarian worldview. The suggestion is that the Nazis fed off “legitimate grievances” about the state of the country, that they put the Jews forward as a convenient scapegoat, and gradually led an unthinking population toward ever further extremes.

This narrative is profoundly misleading. It obscures the true circumstances that led to the Nazis’ rise to power and about the nature of their support base, and it is sloppy history that has been designed for use in domestic culture wars and political battles in America and Britain, and which threatens to discredit the entire field. It has been the basis for tedious moralising by a generation of secondary school history teachers, which has more to do with flattering their own political and social prejudices than it does with anything that happened in the 1930s. This, more than anything, risks alienating young students of history, and driving them toward genuine conspiracy theorists.

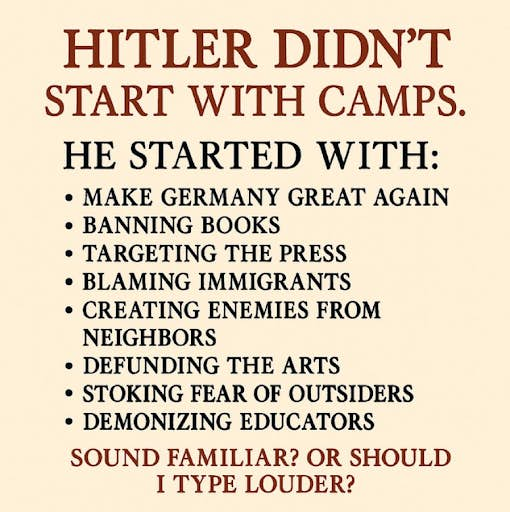

The narrative was summarised pithily in an infographic shared recently by Fernando Oliver, an American lawyer and campaigner with a substantial online following. It is a neat summary of several of the misconceptions that have combined to create a folk-mythology around the rise of the Nazis. This folk-mythology is especially popular among the sort of people who self-identify as being of above average intelligence and who like to imagine Nazism as being aligned primarily against people like themselves.

Firstly, Hitler’s government began working on a concentration camp for political opponents, and what they considered to be antisocial elements, immediately upon assuming power in January 1933. Dachau was opened a few weeks later in March of that year. Whilst this was not a death camp or an extermination camp of the kind seen during the implementation of the Final Solution, it was the beginning of the policy of isolating and concentrating “undesirables” in camp facilities, in which they were deprived of normal civil rights and set aside for whatever fate was intended for them.

Other facilities were established rapidly throughout 1933 and 1934, and by the time the Nuremberg Laws came into effect in 1935, there was an extensive and sophisticated network of camp facilities under SS command across Germany. Hitler very much did “start with camps” as soon as he was in power.

“Make Germany Great Again” is reasonably close enough to Nazi rhetoric that we can let it pass, even though it isn’t a direct translation of Hitler. However that kind of rhetoric was absolutely universal across swathes of the German political spectrum during years after the First World War. It was very obviously a country that had been laid low and was in a reduced state compared to that of a generation previously.

The Nazis did indeed ban books and severely curtail the freedom of the press. They began this as soon as they assumed power, and it was what their voters expected them to do, as they were, quite openly, a totalitarian party. More than just banning books, the Nazis’ rise to power triggered spontaneous mass burnings of books by university students, and demands by students that certain authors be removed from libraries. This is the first sign that all is not quite as liberals might expect, in terms of who it was that was supporting the Nazis.

The Nazis’ attacks on books are often portrayed as evidence of some kind of underlying anti-intellectualism on their part, and of a general dislike of books and reading. It feels odd to discover that there were ardent Nazis in universities. But really, it should follow from the very idea of burning books. Anti-intellectuals do not burn books; they ignore them. Only people who believe that there is some kind of inherent power in ideas would feel moved to such a gesture. In fact, by the late 1920s, Nazi Party voters were a relatively intellectual bunch, with a substantial following among graduates. Teachers were overwhelmingly represented among NSDAP voters, usually doing so at rates 20-30 per cent higher than the general population. This should disabuse us of the idea that the Nazis were “Demonizing Educators” per the infographic.

After they came to power, Nazi personnel assumed control of Germany’s publishing houses, where many of them had already worked. Far from heralding an era of post-literacy, publishing thrived in Nazi Germany, producing works that were either deemed culturally acceptable, or new works that were outright supportive — and much of the reading public in Germany lapped it up. The same can be said of the visual arts, which it is laughably claimed were “defunded”. Allegedly subversive and decadent artists were sidelined, and many fled into exile to avoid criminal investigations. But the Nazis were delighted to fund the kind of art they approved of — lavishly so. The Nazis valued aesthetics at an ideological level, and placed a huge emphasis on spectacle and on the value of beauty to promote their ideals.

The truth is that, unless they were Jewish, German bourgeois intellectuals were basically left alone by the Nazi Regime. Their liberties were curtailed, and if they had mounted serious opposition to the regime they would have been annihilated in very unpleasant ways. Which is why generally, they didn’t. Instead, with a very few exceptions, they were co-opted into the service of the regime, with varying degrees of political coercion and varying degrees of enthusiasm or reluctance. This is in stark contrast to other 20th century totalitarian regimes, in which the intelligentsia were decimated regardless of what they said or did.

English-speaking liberals, trying to press the memory of the 1930s into service in their battles against Donald Trump or anti-immigration populism, seem to have convinced themselves that the Nazis were sustained by similar coalitions of disaffected conservatives, and disgruntled ex-proletarians, harbouring similar resentments against metropolitan liberals and soi-disant intellectuals. This ignores Nazism’s real origins amidst the carnage and destruction of the Western Front, and the complete collapse of German society and the economy that followed. These were times in which totalitarianism, and fanatical ideology promising destructive and violent revolution, did not need to cloak themselves. That was exactly what many people in those circumstances thought was in order.

Whilst in its early years, the Nazis competed against their Communist opponents for streetfighting supporters, within a few years’ years they had generally accepted that either the democratic or the totalitarian left had the edge among the working class, and found more fertile fishing grounds among the small town bourgeoisie in protestant areas. Many of the demobilised veterans who had made up their initial support base had by then returned to the ranks of the small town bourgeoisie from which they originally came, after drifting around during the chaos and penury of the years after the war.

The provincial intelligentsia were people whose gentility had been sorely tested during the war and the depression, who had very little faith in democracy, and who were attracted by the Nazis’ rationalism above all else. Their political resentment regarding their position in society was not aimed at intellectuals or creative types. Many of them saw themselves as provincial members of the same class. Their resentment was aimed at the Jews.

This brings us to the most significant and egregious of the comparisons, which is the attempt to equate Nazi scapegoating of the Jews with contemporary opposition to immigration. German Jews were not an immigrant group in anything like the way in which the term is understood today. There had been a small but continual Jewish presence in German cities since the dawning of German culture and throughout the period of the Holy Roman Empire. Pogroms and exiles had forced the movement of Jews from and between German principalities over the centuries, especially during the Crusades and the Black Death, but these had been reversed over time. There had been a trickle of Jewish immigration from Russia following the revolution and civil war, but due to Germany’s dismal economic situation, many of these migrants had continued on to France, Britain or the United States.

Attempts to recruit the memory of the 1930s and the Second World War for use in contemporary politics inevitably results in vulgar and insulting distortions

Crucially, whatever small inflows of Russian Jews there had been during the 1920s, this stopped completely as it became apparent the Nazis were going to assume power. Their numbers did not continue to grow exponentially during that period, as the rate of immigration into Europe and the United States has done during the period since 2016. The Nazis did not advocate closing Germany’s borders to Jews, or even expelling them; they instead invaded and conquered vast territories where Jews lived in far greater numbers than they ever had in Germany, and summarily murdered them.

Attempts to recruit the memory of the 1930s and the Second World War for use in contemporary politics inevitably results in vulgar and insulting distortions such as this. But this is the end result of a generation of history teaching that has told us that the Nazis are hiding under our beds, waiting to jump out. The temptation to see them in our political opponents is too easy for many to withstand. Trump and today’s immigration sceptics are certainly not the first subject of Hitler comparisons — Thatcher, Reagan and George W. Bush were among earlier targets — though they have grown more acceptable and apparently, more sincere in recent times.

When the BBC released The Nazis: A Warning from History in 1997, it was considered groundbreaking and refreshing. But that was at a time when the war remained a far closer and more personal memory for millions of still relatively young people, on either side of the Atlantic or the Channel. It helped put the conflict into moral and political perspective, rather than the more day-to-day experiences of air raids and rationing and evacuation, in addition to the military history of the war. Nearly thirty years on, and that style of history has stagnated into a cliched and fatuous narrative, that serves neither public understanding of history nor politics. It is time to step back and look at that era in its unique and specific context in order to appreciate its moral enormity, and try to leave our current politics out of the picture.