This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Victor Hervey showed early promise. After trying to wring the necks of the postmistress’s ducks as a child, he went to Eton, to be asked to leave after taking up bookmaking. A spell gunrunning for Franco followed, and then he took to crime — like Raffles, only less successfully. In 1939 he was sentenced to three years in jail for stealing jewellery and a coat. An inveterate liar, he said he had flown fighters in the Spanish Civil War and led an infantry charge with pipers and buglers. He hadn’t.

Hervey, who in 1960 became the 6th Marquess of Bristol, Earl of Bristol, and Baron Hervey of Ickworth (the ancestral seat in Suffolk which his family gave to the National Trust rather than let Victor get his hands on it), is one of the colourful characters in Eleanor Doughty’s new and wide-ranging history of the modern aristocracy. There are many more.

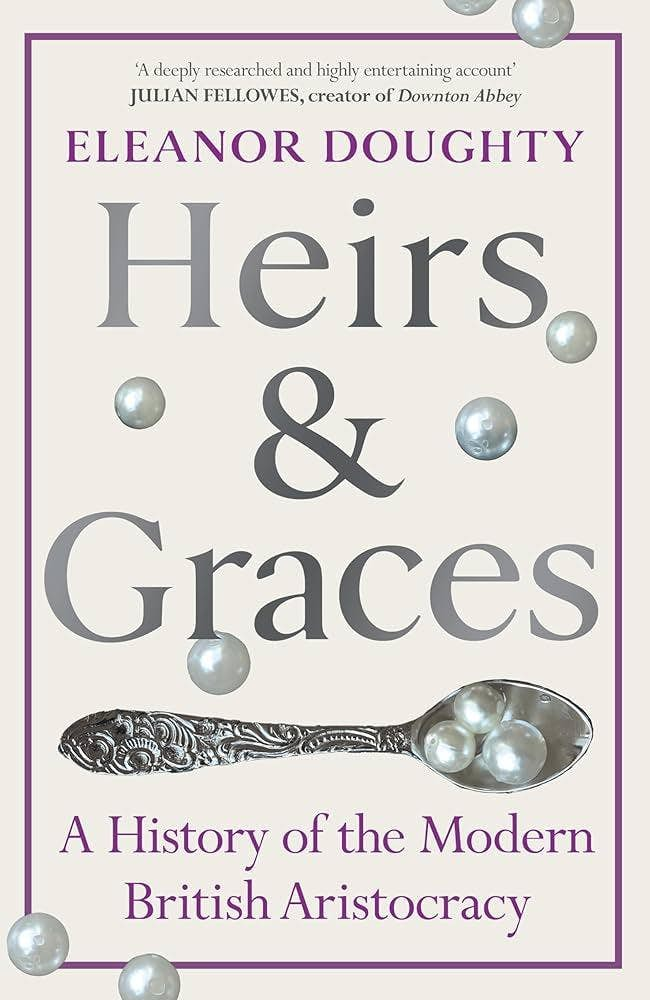

The first four chapters of Heirs and Graces cover familiar territory: the post-war crisis of the country house, the beginnings of the stately home business, the rise of the safari park, the V&A’s 1974 Destruction of the Country House exhibition. But after this, Doughty gets into her stride, and Heirs and Graces becomes an affectionate, if at times ingenuous, portrayal of British nobility, peppered with interviews and reminiscences. She is clearly besotted.

When Doughty visits the Duke of Richmond at Goodwood — “a hint of Tony Blair and a touch of Richard E. Grant” — she is picked up at the station by a Rolls-Royce “worth more than the price of the average UK home”. The Marquess of Lansdowne is referred to with easy familiarity as “Charlie”. The Earl of Derby is a Facebook friend, although she still addresses him as “Lord Derby”. (Relationship: It’s complicated … )

Even the occasional display of aristocratic hauteur does not deter her, as when she visits Woburn Abbey and is told to call the Duke of Bedford “Your Grace” and to stand when he enters the room. She admires his physical presence, his “ducal uniform of shirt and shooting jacket”. In the book, if not in person, she calls him Andrew.

It’s the names that stay with one. Heirs and Graces immerses us in a Wodehousian world filled with people called Bobo and Bobbety and Obbie and Boofy. All we need is a Pongo Twistleton and we’d be back at Blandings Castle. Nor is it just the names. The 11th Baron Middleton once advertised for a new vicar in Horse & Hounds. Lord Emsworth would be proud.

At one point Doughty is shown an old photograph of the 11th Duke of Leeds standing with his new bride, a Serbian ballet dancer; and his mother, who looks “like only a duchess would look if your only son is marrying a Serbian ballet dancer”. Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 5th Earl of Cranbrook, has a species of white-toothed shrew named after him. Lord Mancroft is honest about his childhood in the 1960s: people always say to him how awful it must have been to be brought up by a nanny, but “if I’d been raised by two blithering idiots like my parents, I’d be a complete psychological wreck”.

Every now and then, though, one yearns to call for the tumbrils. During the war, times were so hard at the Somersets’ Wiltshire country house that the Duchess of Somerset had to do her own cooking; and after it the Onslows of Clandon were so poor they had to sell their cock-fighting table (a Chippendale, too). Sir Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd and his wife scraped by with just a butler, a cook, a pantry boy, two housemaids and a chauffeur.

In 1988, the Lincolnshire squire the Revd Henry Thorold in a letter to the Daily Telegraph attacked the government for not helping ancient families, declaring that “it is a horrifying thought that any nouveaux riches should replace such families … in their historic houses”. Horrifying? Not really, Reverend. Five years later, when asked whether a spell in jail for drug offences had changed him, the 7th Marquess of Bristol, son of Victor, replied, “Christ, no! It might work for stupid people, but it’s designed for the lower classes really, isn’t it?”

The temptation is to pounce on utterances like these as evidence that the British aristocracy is riddled with snobbery and contempt for the masses. But that wouldn’t be fair. Some of Doughty’s toffs have an exaggerated sense of their own importance; others are pathologically modest. Some are nice. Some are not. A bit like ordinary people, really.