Infertility is something that affects millions of people around the world – often caused by problems with the egg.

Now, scientists have taken a huge step towards helping many women have their own genetic children.

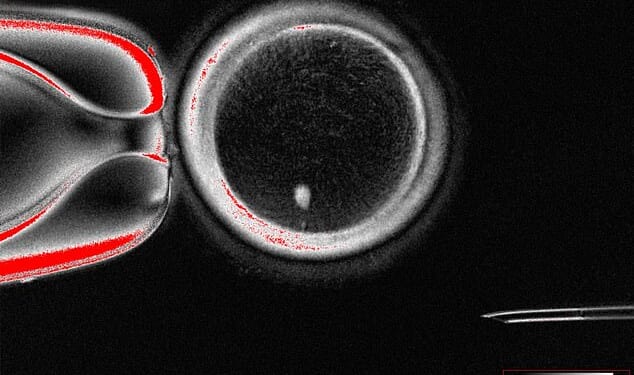

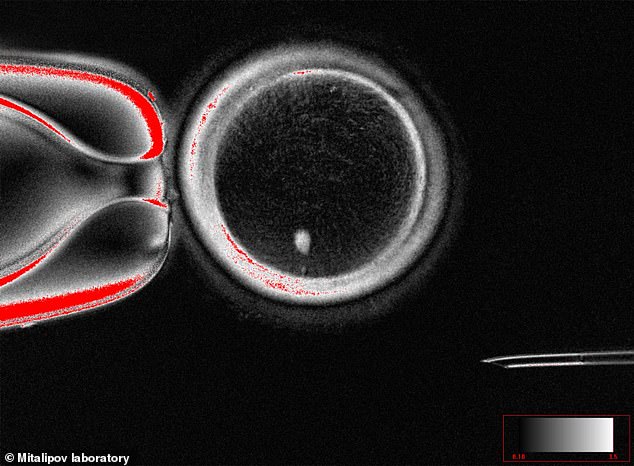

Experts from Oregon Health & Science University have created fertilizable eggs from human skin cells for the very first time.

While further research is needed to ensure safety and efficacy before clinical trials can go ahead, experts have described the news as a ‘major advance’.

‘Many women are unable to have a family because they have lost their eggs, which can occur for a range of reasons including after cancer treatment,’ said Professor Richard Anderson, Deputy Director of MRC Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the study.

‘The ability to generate new eggs would be a major advance.

‘This study shows that the genetic material from skin cells can be used to generate an egg–like cell with the right number of chromosomes to be fertilised and develop into an early embryo.

‘There will be very important safety concerns but this study is a step towards helping many women have their own genetic children.’

Experts from Oregon Health & Science University have created fertilizable eggs from human skin cells for the very first time

For some couples struggling to conceive, in virto fertilization (IVF) can be an option.

This treatment sees the eggs fertilized by sperm in a lab, and the resulting embryo then placed in the woman’s uterus.

However, if there’s a problem with the egg itself, IVF can be ineffective.

Previous studies have suggested that a method called ‘somatic cell transfer’ could be an alternative approach.

This process involves transplanting the nucleus from one of a patient’s own somatic cells (such as skin cells) into a donor egg cell with the nucleus removed, enabling the cell to differentiate into a functional egg.

However, while standard eggs have half the usual number of chromosomes (one set of 23), cells generated from skin cells have two sets of chromosomes (46).

Without intervention, this would cause the differentiated eggs to have an extra set of chromosomes.

So far, a method to remove this extra set has been developed and tested in mice – but is yet to be tried in humans.

For some couples struggling to conceive, in virto fertilization (IVF) can be an option. This treatment sees the eggs fertilized by sperm in a lab, and the resulting embryo then placed in the woman’s uterus (stock image)

In their new study, the team resolved this issue by inducing a process they’ve named ‘mitomeiosis’.

‘[Mitomeiosis] mimics natural cell division and causes one set of chromosomes to be discarded, leaving a functional gamete,’ the researchers explained in a statement.

During tests, the researchers were able to produce 82 functional eggs using this process, which were then fertilised in a lab.

Approximately nine per cent went on to develop the the blastocyst stage of embryo development.

However, the researchers did not culture the blastocysts beyond this point, which coincided with the time at which they would usually be transferred to the uterus in IVF treatment.

While the findings raise the tantalising possibility of women with problems with their eggs having their own genetic children, the experts note several limitations with their study.

Importantly, the vast majority (91 per cent) did not progress beyond fertilisation.

What’s more, several of the blastocysts were found to contain chromosomal abnormalities.

Regardless, experts have called the research an ‘exciting proof of concept’.

‘This breakthrough, called mitomeiosis, is an exciting proof of concept,’ said Professor Ying Cheong, a professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Southampton, who was not involved in the research.

‘In practice, clinicians are seeing more and more people who cannot use their own eggs, often because of age or medical conditions.

‘While this is still very early laboratory work, in the future it could transform how we understand infertility and miscarriage, and perhaps one day open the door to creating egg- or sperm-like cells for those who have no other options.’