There is urgency in Yamah Sheriff’s voice.

As rain lashes down on this Monday afternoon in July, she doles out clipped orders to the workers gathered around her: Clear the undergrowth. Repair the palm leaf fence.

In a few days, local teenage girls will arrive in this secluded spot at the edge of the village for what is known here as a bush school, a pivotal rite of passage where they will be initiated as women.

Why We Wrote This

Efforts to end female genital mutilation often fail because they don’t have the buy-in of communities for which the practice is important. In Liberia, activists are asking: What would make change stick?

As part of that initiation, Ms. Sheriff and other older women from the village will perform female genital mutilation (FGM) on the girls.

In recent years, many countries have banned FGM, but Liberia remains a stubborn holdout. In April, its government temporarily prohibited the operation of bush schools such as Medina’s until January 2026. Then, last week, President Joseph Boakai pledged at the U.N. General Assembly to permanently ban the practice. But many say these prohibitions have a fundamental flaw: They lack buy-in from the women who perform FGM themselves.

Ms. Sheriff, for instance, says her motivation is stronger than any law. “I cannot abandon my cultural duties,” she explains.

An essential rite

Ms. Sheriff is a Zoe, one of the leaders of a Liberian secret society called the Sande, of which the vast majority of rural Liberian women are members. To join, a girl must undergo FGM.

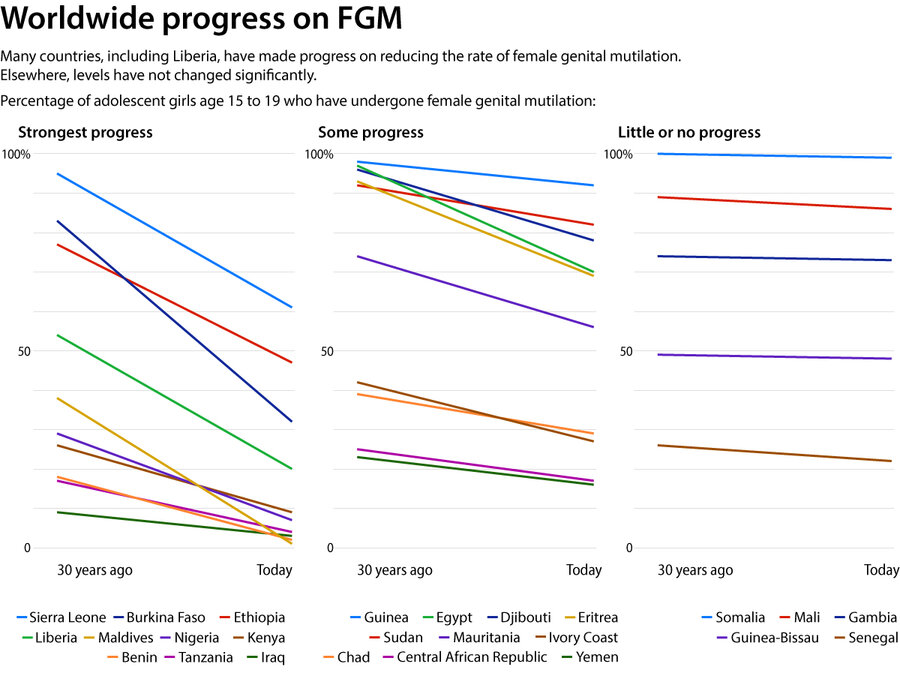

In Liberia, about one-third of women between ages 15 and 49 have been cut, according to UNICEF, and globally, the figure is 230 million. In recent decades, a groundswell of global outrage against FGM – a blanket term for the mutilation of female genitalia without medical purpose – has led to bans on the practice in many countries.

Liberia has also attempted a number of times to outlaw it. But like the suspension of the bush schools, these bans have always been temporary, and largely unenforceable.

The reason, experts say, lies in the complex web of economics, politics, and culture that sustains FGM here. Many Zoes are highly economically reliant on running bush schools. But more fundamentally, they – and their communities – see FGM as essential to girls becoming women in Liberian society.

“I passed through it, and I am happy my baby girl is now a member [of the Sande],” explains Quinee Sackie, whose 13-year-old was recently initiated in Bombama, a town near Medina.

Indeed, in much of rural Liberia, traditional culture is fiercely defended. Women in Medina can be fined $15 for wearing trousers or clothes that show their arms or legs. Elsewhere, a radio journalist was brutally beaten in July after he announced on air the ban on bush schools run by the Sande and the Poro – a parallel secret society that initiates boys.

So it comes as little surprise to many that despite the ban, “parents continue to bring their children” to bush schools, says Hawa James, a Zoe from another town who was recruited to assist with the initiation in Bombama.

A cultural evolution

Ms. James’ story illustrates the complexity of efforts to end FGM here. Two years ago, she was recruited into a project by the charity ActionAid International that taught Zoes about the health risks of FGM and gave them loans to pursue farming and other professions. Over the next year, the project signed up more than 100 women, many of whom became passionate advocates against FGM.

Ms. James completed the program, but when she was asked this year to assist with Bombama’s bush school, she didn’t hesitate. “We Zoes support one another,” she says.

Her continued participation in bush schools puzzles aid workers like Foxter Janemama, who helped recruit Zoes for the ActionAid program. “We still have a lot of work to do,” he says.

But Ms. James’ decision reflects deeper forces at play. Close to 9 in 10 Liberians belong to ethnic groups with Sande and Poro secret societies, and many political leaders rely on voters with ties to the groups. The Zoes, in turn, capitalize on that influence. Their work is “mainly for economic and political gain,” Mr. Janemama argues.

Still, some Zoes have been open to change. Massa Kandakai, formerly the head Zoe in Montserrado County, decided to quit her work in 2019 after participating in an educational program similar to the one Ms. James went through.

“Gone are the days when Sande bush [schools] used to teach people about culture,” she explains. “Now everything is on the internet.”

“Initiation without mutilation”

In the capital Monrovia, lawmakers are currently reviewing a draft bill to prohibit FGM permanently, and it appears to have the support of the country’s president. For months, they have deliberated with community leaders from across the country about the contents of the proposed law.

This is part of an effort to get the grassroots buy-in that previous bans have lacked, says Moima Briggs Mensah, chair of the Legislative Committee on Gender Equity, Child Development, and Social Services in Liberia’s House of Representatives. For instance, a proposed law would allow bush schools to continue to operate, so long as they did not practice FGM. Ms. Mensah calls this idea “initiation without mutilation.”

Proponents believe this compromise will bridge the conflict between preserving cultural practices and protecting girls from harm. But skeptics question whether such measures address the fundamental issue: Many Liberians still see FGM as necessary for girls to gain social acceptance as women.

But back in Bombama, this debate feels far away. Ms. James is focused on her work. Throughout the summer, the town’s girls have streamed into the bush school for their initiation. By mid-August, Ms. James says matter-of-factly, the school had initiated 302 girls.

This piece was published in collaboration with Egab.