A recurrent theme during the past decade of American politics has been the repeated calls for censorship of “hate speech” or “misinformation” on the internet, mostly coming from the political left. One way that many believe they could circumvent the First Amendment and enforce censorship on the internet is through reform of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. Worryingly, besides the usual Democratic suspects, some Republicans have started calling for Section 230 reform and internet censorship.

In a recent appearance on NBC’s Meet the Press, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) decided to blame social media, rather than left-wing extremism, for the murder of Charlie Kirk, and called for reform to Section 230. “Section 230 needs to be repealed,” Graham said. “If you’re mad at social media companies that radicalize our nation, you should be mad.” But what exactly is Section 230? And why is Graham calling for it to be “repealed” to stop “radicalization?”

While most Americans may not be familiar with Section 230, all benefit from it: It is responsible for much of our ability to speak freely online. Without it, it is hard to see how social media would have taken off in the first place. At its core, Section 230 simply prevents computer service providers, including social media companies, from being treated as publishers by law, meaning that they do not have civil liability for user-generated content on their platforms. Instead of being treated as the publishers of the content on their platforms, social media companies are treated as distributors, which means they are only liable for violations of human trafficking laws, intellectual property laws, and the spread of criminal materials.

In practice, Section 230 ensures that social media sites do not have to worry about frivolous lawsuits over content on their platforms constantly. For instance, if a social media user posts a defamatory comment on a particular site, the social media site cannot be held responsible. As a result, Section 230 has the de facto effect of benefitting free speech, as platforms can allow people to express a wide range of views without facing continuous lawsuits over user posts and the opinions expressed therein.

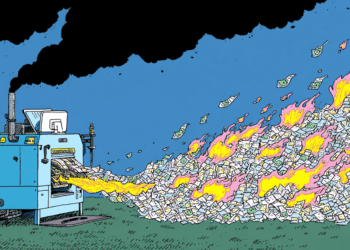

Because of this, Section 230 is a prime target for would-be internet censors. In July 2021, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM) put forward a bill that would make social media companies liable for “health misinformation” during a “public health emergency.” Klobuchar’s statements at the time show that it was her intent for the government to force social media companies to censor criticism of the Covid vaccine, lest they be held liable for Covid deaths.

“These are some of the biggest, richest companies in the world, and they must do more to prevent the spread of deadly vaccine misinformation,” the Minnesota senator stated at the time. “The coronavirus pandemic has shown us how lethal misinformation can be, and it is our responsibility to take action.” Klobuchar’s bill, had it passed, would have forced social media companies to censor those airing criticisms of the Covid vaccine, including those whose complaints proved to be correct.

Apart from potential censorship surrounding medical issues such as the Covid vaccine, some politicians have floated Section 230 reform as a way to censor “hate speech”. Beto O’Rourke, during his 2020 Democratic presidential campaign, stated that he favored reforming Section 230 to “remove legal immunity from lawsuits for large social media platforms,” should they refuse to proactively remove “hate speech” and terrorist content.

“We must connect the dots between internet communities providing a platform for online radicalization and white supremacy,” O’Rourke’s campaign website read. Given that elements of our country’s cultural and political elite have defined things as banal as hard work or timeliness as part of malignant “whiteness,” it is entirely reasonable to expect that O’Rourke’s proposed change would have censored normal opinions held by a majority of Americans.

In 2021, several House Democrats introduced HR 5596, also known as the “Justice Against Malicious Algorithms Act,” which likewise would have amended Section 230 to remove liability protections for social media companies with algorithms that deliver content that “materially contributed to a physical or severe emotional injury to any person.” One of the bill’s co-sponsors, Rep. Frank Pallone (D-NJ), admitted that the bill was about censoring the opinions of Americans.

“By now it’s painfully clear that neither the market nor public pressure will stop social media companies from elevating disinformation and extremism, so we have no choice but to legislate, and now it’s a question of how best to do it,” Pallone said during the bill’s announcement.

Given the difficulty of passing laws along partisan lines, the greatest threat to free speech on the internet would come from bipartisan action on the issue. In the aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, an exchange at a congressional hearing with FBI Director Kash Patel hinted at possible bipartisan collaboration to censor social media through Section 230 reform. After complaining about conspiracy theories, including “conspiracies about [Patel’s] personal social life,” Rep. Jared Moskowitz (D-FL) suggested to him that “if we want to do something, we should talk about Section 230.” Rather than shooting down this suggestion of censorship over “conspiracy theories” about the personal lives of those in government, Patel, a Republican appointee, instead told Moskowitz, “I’ll work with you on 230 any day.”

There have been other recent bipartisan attempts to censor the internet. In July, Reps. Don Bacon (R-NE) and Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ), together with ADL chief Jonathan Greenblatt, held a press conference to announce the introduction of their new bill, the Stopping Terrorists Online Presence and Holding Accountable Tech Entities (STOP HATE) Act. In the press conference, these men admitted that their bill was explicitly drafted to combat “antisemitism” and “misinformation” (both of which are meaninglessly broad categories) on the internet in the aftermath of October 7. During the announcement, Bacon justified the bill as a means to make it so that “racism” and “antisemitism” are “not allowed” online and taken “off the airwaves”:

We want to be in a country that makes clear that antisemitism or any kind of racism is repugnant, unacceptable, not allowed in an online space…..We need to work with our social media companies to clean this up because what is going on is wrong. We need to hold these companies accountable and work with them to take it off the airwaves.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Even if changes to Section 230 require federal action, there is already evidence that some states would also be willing to promote online censorship. The California legislature recently passed a bill, SB 771, that would fine social media companies for amplifying “violent” or “extremist” content, and would include hefty fines for social media companies that “knowingly” promote posts that violate California’s civil rights laws. This would penalize posts “engaging in, aiding, abetting, or conspiring to commit acts of violence, intimidation, or coercion based on race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, immigration status, or other protected characteristic” with fines of up to $500,000 should a company “recklessly” promote such a post through its algorithm, and $1 million, should it “knowingly” do so. The text of the bill justifies itself by citing past instances of hate crimes involving anti-immigrant slurs” and “anti-LGBTQ+ disinformation and harmful rhetoric,” “anti-Jewish bias” and “anti-Islamic bias.” (Anti-white or anti-Christian discrimination is not mentioned.) This bill, which would have a chilling effect on free speech on social media platforms (given the size of California’s population), currently awaits Governor Gavin Newsom’s signature.

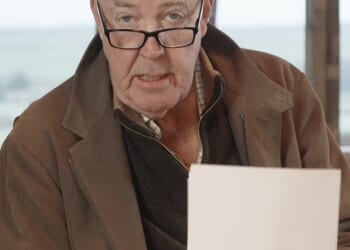

While these bills may seem like a minor threat to most Americans, the majority of whom are genuinely decent, history shows such laws would be liberally interpreted. The result would likely be a situation like that in the contemporary UK. In 2023, an average of 30 people per day, or over 12,000 people, were arrested in the UK for online speech. By contrast, over the course of the same year in Russia, which is often called “authoritarian” by our media, there were only 3,313 cases (483 criminal and 2,830 civil) for political offenses. Despite being at war and having over twice the population of Britain, Russia’s total political offenses numbered just over a quarter of the arrests made in Britain purely for internet speech.

If Americans wish to avoid the dark path that Great Britain has found itself on, we must oppose actions that could lead to censorship, including reforms to Section 230.