Out of date legislation and an ambiguous China policy may have collapsed the Westminster spying case

UK prosecutors announced on 15 September that the case of two men accused of spying for China would not go to trial.

Christopher Berry, a teacher, and Christopher Cash, a researcher working at the heart of government, were both arrested in 2023. They denied the charges under the Official Secrets Act. Cash was accused of abusing his position as director of the China Research Group to pass information to Berry, who wrote reports for a CCP operative called “Alex.” The pair said that Alex was nothing more than a businessman keen to trade with the UK.

When the case was dropped, Westminster was awash with rumours of a CCP-led cover-up, with Starmer’s official spokesperson calling the move “gravely concerning.” Yet comments from inside the Crown Prosecution Service suggest that the charges collapsed for a less glamorous legal reason after lawyers were unable to meet the evidence threshold; or crucially, prove that China is “an enemy.”

Parts of the Official Secrets Act have not changed since 1911, and hinge on the definition of “enemy,” a word which leaves no diplomatic wiggle room. A spy is a person who “obtains, collects, records, or publishes, or communicates to any other person any secret official code word, or pass word, or any sketch, plan, model, article, or note, or other document or information which is calculated to be or might be or is intended to be directly or indirectly useful to an enemy.”

Recent British espionage cases involved Russia and Iran — countries the Foreign Office openly condemns, sanctions, and mistrusts. When Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the City walked away from three decades of investment, called in consultants to ensure sanctions compliance, and cut the ties of friendship with Moscow. On paper, Britain’s position is very clear.

Without legal reform we may never find out whether there was a real attempt to infiltrate Westminster

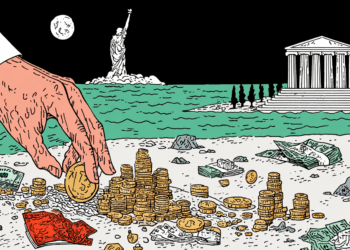

Yet despite China flaunting its military drills with Russia, Beijing faces no such backlash. China is Britain’s fifth-largest trading partner. Trade between Britain and China in 2025 brought in £99.7 billion, with the year far from over. In economic terms at least, China is welcomed as an ally. Had the trial gone ahead, Cash and Berry were expected to maintain that they were trying to act in Britain’s interest; these kinds of numbers could scarcely have harmed their argument.

Mixed messaging on China is nothing new. Boris Johnson’s government was accused of deliberating itself into a “strategic void” on China — putting out opaque messaging that allowed the UK to take advantage of lucrative trade deals whilst simultaneously condemning human rights abuses, warning of military encroachment in the Pacific, and removing 5G equipment over surveillance fears. And lest we forget, Liz Truss established herself as a China hawk, and was later found to have secretly lobbied to speed up the sale of arms to Beijing.

This is the China policy Starmer inherited — and cake is still being had and eaten. The latest strategic defence review describes China as “a sophisticated and persistent challenge” and acknowledges that Chinese alignment with hostile countries has increased, but does not go as far as discouraging deals in the sectors where the UK and China still cooperate.

Most people would recognise that there are countries that fall between the categories of “ally” and “enemy” — but our laws — in particular the creaking Official Secrets Act — do not reflect this messy reality. Whilst newer laws like the National Security Act provide more nuance, prosecutors can struggle to apply them. In the case of Cash and Berry, CPS chief Stephen Parkinson said his team had considered alternate charges, and concluded “none were suitable.”

Without legal reform we may never find out whether there was a real attempt to infiltrate Westminster on the part of the CCP. It is frustrating to see a trial collapse that could have shed light on Chinese intelligence gathering in Britain — but it is wrong to insist on the existence of a CCP-led cover-up simply because the charges were dropped.

Rather than crying foul, the government could be using this moment to clarify how anti-espionage legislation applies to the hundreds of British companies, NGOs, and individuals who work with China. As long as this grey area remains in the law, anyone who studies, trades with, or has regular contact with another country lives with the risk that the country may be redefined as “hostile” at any point. They have a right to know whether they are protected.