Winston Churchill sat up in bed, scattering sheafs of state papers, his prominent blue eyes welling with tears. He had just been told that his wartime friend King George VI had died.

His private secretary did his best to console him, telling him how well he’d get on with the new Queen. But the only thing the 77-year-old Prime Minister could say was that he didn’t know her – and that she was ‘only a child’.

It was an inauspicious start to the reign of Elizabeth II, and hardly a good portent for her relationship with Winston Churchill.

In fact, he did know her, though not well. He’d first encountered her at Balmoral when she was a self-possessed two year old, well before the abdication of her uncle King Edward VIII made her heir presumptive to the throne.

Back then, Winston had been remarkably prescient. Not only had he described the toddler as having ‘an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant’, but he’d even referred to her as Queen Elizabeth. No one knew if he was making a joke or a prophecy. For now, though, on February 7, 1952, his thoughts were chiefly for his old friend George VI.

En route to London airport to meet the new Queen – who’d been in Kenya when her father died – he sat in the back seat of his limousine, dictating a valedictory speech to his secretary. Tears blurred his vision, cascading down his cheeks. (Not for nothing had the Duke of Windsor called him ‘Cry Baby’ behind his back.)

In a broadcast to the nation that night, Winston spoke movingly about the late King and pledged fealty to the new sovereign. Privately, however, he had reservations about the Queen’s capacity to fill her father’s shoes.

She was only 25, after all; a young mother with a thin, high voice who’d yet to be thoroughly tutored in the many responsibilities of the crown. This task, Churchill recognised wearily, was one that would fall to him, as her first Prime Minister.

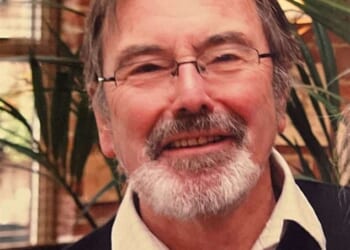

Winston Churchill with then-Princess Elizabeth in 1950 at a Guildhall reception in London

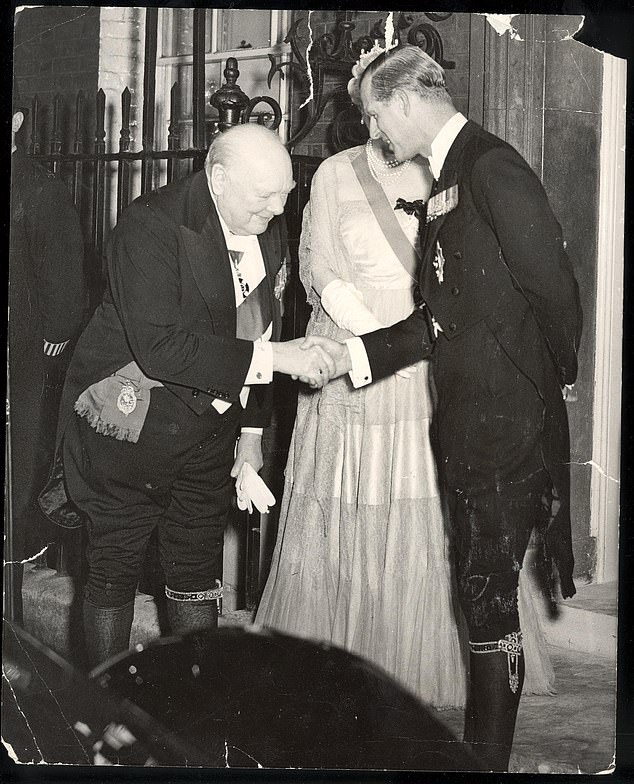

Prince Philip bids Churchill farewell outside Downing Street after dining with Queen Elizabeth

Days later, he had his first audience with her at Buckingham Palace. The Queen no doubt felt nervous, even intimidated. Although Winston had been a familiar figure during her teens, she was all too aware he was a national hero.

Remarkably, however, that first audience completely changed Churchill’s attitude to her. Immediately afterwards, he praised the naturalness with which the Queen had stepped into her new role. He no longer saw her as merely ‘fair and youthful’, but as a competent, prudent and steadfast woman.

The following morning, he wrote to a friend: ‘I am sure that in [George VI’s] daughter we have one who is in every way able to bear the heavy burden she must now carry.’

Even Elizabeth noticed the sudden change in her own manner. ‘I no longer feel anxious or worried,’ she told a friend in the first days of her reign.

She was as baffled as anyone by her transformation, but suggested that her audience with Churchill was fundamental: ‘I don’t know what it is, but I have lost all my timidity somehow becoming the Sovereign and having to receive the Prime Minister.’

One of the first problems Winston had to deal with was the Queen’s head-strong husband. As Philip was to discover to his cost, there were three of them in the marriage and at times it got rather crowded.

The first problem involved his own surname, Mountbatten, which had been anglicised by his uncle Lord Mountbatten. Just two days after the King’s funeral, the grieving Queen Mary was told that Prince Philip’s uncle had proudly announced at a dinner party that ‘the House of Mountbatten now reigned’. Outraged, she contacted Churchill’s private secretary and asked him to brief the old man.

Churchill was equally perturbed. Not only did he consider Lord Mountbatten pompous, boastful and overly concerned with titles, medals and rank, but the notion of applying the name Mountbatten to the Royal House struck him as downright absurd.

From left to right: Princess Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, Winston Churchill, King George VI and Princess Margaret on the balcony at Buckingham Palace on Victory Day 1945

Churchill was instrumental in ensuring the Royal Family retained the name of Windsor

After all, the original surname was Battenberg, until its Germanic origins had been anglicised during the First World War to counter anti-German sentiment.

Moreover, King George V had deliberately proclaimed Windsor to be the Royal Family’s surname in 1917, again to mask the family’s German origins.

For the sterling new reign to be tarnished by a return to the Germanic lineage, so soon after the German threat had been defeated a second time, struck Churchill as nothing less than an affront.

Prince Philip, however, was insistent that his children should bear his surname – and precedent was on his side. Even Queen Victoria – that bastion of social propriety – had allowed the surname of her husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, to be passed on to their issue.

Churchill ignored this. In the following weeks, he drafted a proclamation with the Privy Council that ensured the royal children would be Windsors. Spitting mad, Philip sent a memo to Churchill, arguing against the decision. All it accomplished, however, was to further irritate the PM, who instructed that ‘a firm, negative answer’ be sent.

Finally, on April 6, Queen Elizabeth formally declared her ‘Will and Pleasure’ that both she and all her children would maintain the title of the House of Windsor.

Inevitably, this caused a rift between husband and wife. As politician Rab Butler observed, it was the only occasion where he saw her close to tears.

A further source of tension was the question of where the Royal Family should live. As far as Philip was concerned, there was no good reason to move from Clarence House, which had been the family’s home since 1949.

Prince Philip wanted any children he and Queen Elizabeth had to inherit his Mountbatten surname

Until then, he’d spent much of his life on the move, so he’d cherished the opportunity to put down roots. Not only had he chosen all the paint colours, the drapes and the carpets, but he’d even installed the latest gadgets, such as a motorised wardrobe.

The Queen was also inclined to stay put, especially since her mother and sister were in no rush to vacate Buckingham Palace. For the Queen Mother, just the idea of being evicted from the home she’d shared with her late husband was enough to bring her to tears.

But Churchill argued strongly that the constitution took precedence. The flagpole at Buckingham Palace ‘flies the Queen’s Standard and that’s where she must be’, he declared firmly. Craftily, he recruited the Queen’s veteran private secretary, Tommy Lascelles, to convince her that she and her family must move ‘across the road’.

Again, Prince Philip was dragged kicking and screaming into this revised arrangement. And everyone knew the Prime Minister was responsible. By this point, Philip was privately referring to Churchill as an ‘old bastard’.

It seemed the prince could do nothing right. That spring, when he attended a debate in the House of Commons – as an observer – he was seen making overly expressive faces at the policy positions articulated by various speakers.

Some MPs were scandalised, complaining it was constitutionally inappropriate as well as unbecoming for a royal consort to display any personal judgment on a political matter.

Churchill received a formal letter of complaint from the Conservative MP Enoch Powell. The chief whip endorsed the complaint, and the PM then conveyed it to the monarch.

‘It kept happening,’ recalled Philip’s friend Lord Brabourne. ‘Philip was constantly being squashed, snubbed, ticked off, rapped over the knuckles. It was intolerable.’

Although Churchill was the first to chastise Prince Philip when he stepped out of line, he recognised that he was ‘insupportable when idle’, and needed something to keep him busy.

It was small beer, but the prince was granted a leading advisory role in the Royal Mint’s project to manufacture new coins and medals bearing Elizabeth’s likeness. He was also appointed Chair of the Coronation Commission, on which Churchill also served, which predictably led to fireworks.

Most tense of all was the question of whether the 1953 Coronation should be televised. Philip thought it essential that the monarchy show itself up to date with the times. Churchill, for his part, considered that a broadcast, watched by people drinking in the pub or slouched in their pyjamas, would desecrate the ceremony.

Philip was once again on the losing side – until the sheer strength of public opinion forced the PM reluctantly to accept the presence of TV cameras.

There was another rare defeat for Winston when he tried to ban the prince from learning to fly jet aircraft, on the grounds he was exposing himself to unnecessary risks. This time, the Queen sided with her husband, allowing him to pursue his hobby.

Meanwhile, Winston tried to keep his distaste for Philip under wraps. But it soon became known among the Number 10 secretariat that ‘although he wished the Duke of Edinburgh no ill, he neither liked nor trusted him and only hoped that he would not do the country harm’.

The Queen was in an invidious position: loyal to Philip yet determined to do her constitutional duty. Over time, however, despite Churchill’s frequent tussles with her husband, she found herself increasingly enchanted by her Prime Minister.

It helped that they shared two great passions: racing and the breeding of horses.

Within months of her accession, her weekly meetings with the PM, slated to last half an hour, had often turned into free-wheeling discussions that went on for another hour.

Tommy Lascelles, who ushered Churchill into the Bow Room and then waited for him outside the door, couldn’t hear what they discussed, but noticed that the audiences were, ‘more often than not, punctuated by peals of laughter’.

One evening, Churchill was especially enamoured: ‘She’s en grande beauté ce soir,’ he told Lascelles, in ‘schoolboy French’.

The Prime Minister’s unusually long meetings with the Queen caused a great deal of curiosity. ‘What do you talk about?’ Churchill’s private secretary Jock Colville asked him one day.

‘Oh, mostly racing,’ Churchill responded vaguely. Of course, they also tackled more sober topics, such as Britain’s place in the world, parliamentary gossip and public personalities. And Churchill was impressed by how quickly the new Queen took up her role.

‘Her immediate grasp of the routine business of kingship was remarkable,’ he wrote. ‘She never seemed to need an explanation on any point.

‘Time after time I would submit to her papers on which several decisions were possible. She would look out of the window for half a minute and then say: ‘The second or third suggestion is the right decision’ – and she was invariably right.

‘She had an intuitive grasp of the problems of government and indeed of life generally.’

He was clearly bowled over. One day, he picked up a photograph of the Queen and muttered: ‘Lovely, inspiring. All the film people in the world, if they had scoured the globe, could not have found anyone so suited to the part.’

Some worried he might be too quick to bow to her will. Even her assistant private secretary, Edward Ford, noticed how Churchill ‘acted upon her lightest word’. One of their meetings, for instance, took place the day after the Queen had attended a screening of Beau Brummell, which had been selected for her with the expectation that she’d enjoy seeing a historical film about Kings George III and IV.

In fact, she found the film unsettling and distasteful.

When Churchill learned that she hadn’t enjoyed it, he was horrified, and left the audience muttering: ‘The Queen has had an awful evening. This must not recur.’

By the following day, he’d told the Home Secretary to arrange a formal review to scrutinise the choice of films to be screened for the sovereign.

But for all his eagerness to please her, Churchill – as Philip had discovered – was no pushover.When Sir Richard Molyneux, a former courtier, asked Elizabeth if Winston played the part of the ‘over-indulgent’ Lord Melbourne to her Queen Victoria, she laughed. ‘On the contrary,’ she replied. ‘I sometimes find him very obstinate.’

Churchill was predictably unhelpful when she asked for a change to the 1937 Regency Act, which specified that Princess Margaret would serve as a Regent in the event of the Queen’s absence or incapacitation. Instead, she wanted Philip to be Regent until Charles, then aged four, came of age.

Winston was unconvinced, feeling the public might think she mistrusted her sister. Privately, he also had serious doubts that Philip was the appropriate choice.

But he was forced to change his mind after Princess Margaret declared her wish to marry a divorced man – her late father’s equerry, Group Captain Peter Townsend.

Along with his Cabinet, Winston took the view that Margaret should renounce her rights to the throne if she chose to pursue the relationship.

In the end Margaret took the painful decision to part from Townsend. Seared by the scandal, Winston finally backtracked, agreeing that Philip should replace Margaret as potential Regent.

Aside from Philip, the PM had another royal headache to deal with: Elizabeth’s mother, now demoted in her early 50s from Queen to Queen Mother. Since King George VI’s accession in 1936, she’d been accustomed to taking pole position at all formal events.

Now that she was a widow, she was finding it difficult to cope with her new place in the pecking order.

In the weeks following the new Queen’s accession, observers noticed that there was an ‘awkwardness about precedence’.

Sensitive to her mother’s feelings, Elizabeth was allowing the old queen to walk in front of her at formal ceremonies and to take the monarch’s seat at Sunday church services.

Something had to be done, particularly as the Queen Mother was now hiding away in Scotland and talking of bowing out from public duties altogether. But Winston knew that trying to persuade her otherwise would be a delicate mission.

At first he’d considered making her the Governor General of Australia, but that idea fizzled out. Then, in October 1952, he decided to visit her at Birkhall, her Scottish home. Before going, he tested the water with her lady-in-waiting, who advised he should arrive unannounced. So he did – and soon found himself having a heart-to-heart conversation with the Queen Mother.

She was not only grief-stricken, he discovered, but felt that the significance of her life as Queen had been abruptly and cruelly snatched away with the death of her husband. It had also been hard to come to terms with her swift demotion in the court hierarchy, she confided.

Though Churchill was sensitive to her plight, he was also aware that the Queen Mother was a great asset for the monarchy and the nation. During their conversation, he swiftly snuffed out any discussion of retirement.

‘Absolutely not!’ he told her. ‘This young Queen is going to need you by her side an awful lot. And this is no time for you to sit in Scotland.’

Winston also emphasised how valued she was, not just by her immediate family and friends, but by the nation at large. She needed to be inside the loop of society, rather than cutting herself off, he said.

He clearly worked his magic.

One of the Queen Mother’s ladies-in-waiting, Jean Rankin, noticed an immediate change in her demeanour, speculating that Churchill ‘must have said things which made her realise how important it was for her to carry on, how much people wanted her to do things as she had before’.

Of the many services Churchill performed for the Royal Family during his lifetime, the way he wrangled the Queen Mother back into the royal fold was one of the more significant.

Her links to the wartime generation, her military associations and her innate charm would add an extra dimension to the new reign.

Arguably, no one but her late husband’s friend and wartime Prime Minister could have persuaded her to re-dedicate herself to public service. For this, Winston Churchill would earn his new Queen’s undying gratitude.

Adapted from Winston And The Windsors, by Andrew Morton, to be published by Michael O’Mara on October 9, £24.99. © Andrew Morton 2025. To order a copy for £21.25 (offer valid to 18/10/2025; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937