In the last message she ever sent to her mother, Fawziyah Javed said she was heading out for a walk during an Edinburgh getaway with her husband.

It was a walk from which she never returned.

‘I texted her later that night to ask how it was, and when she didn’t reply I assumed she had just gone to bed early as she was tired,’ says Yasmin Javed.

In fact, Fawziyah was dead, her parents learning the devastating news when they opened their front door in Leeds to two plain-clothed female officers at 5am the next day.

‘I remember rubbing my eyes, because I thought I have to be asleep, this couldn’t be real,’ Yasmin says, her eyes filling with tears. ‘But straightaway I knew instinctively that her husband was involved.’

Indeed, during the evening of September 2, 2021, 31-year-old Fawziyah – a bright, charismatic lawyer who was 17 weeks pregnant with her first child – was pushed off a cliff at popular tourist attraction Arthur’s Seat by Kashif Anwar, plunging 50 ft to her death.

Barely conscious, she used her last breaths to tell witnesses and the police that the man she had married just eight months earlier – and who she had planned to leave the moment they returned from holiday – was responsible.

Along with the records Fawziyah courageously kept of her husband’s abuse, that dying testimony helped to secure his conviction for her murder and that of her unborn son.

Fawziyah Javed, pictured on her graduation day, was killed by her abusive husband

Fawziyah’s mother Yasmin Javed, says her daughter did everything possible to leave her abusive relationship

Fawziyah and her mother Yasmin together

In April 2023, Anwar was jailed for a minimum of 20 years.

The loss of their only child – along with their eagerly anticipated grandson – has devastated her parents.

‘We are just existing, not living,’ says Yasmin. ‘Fawziyah’s last words ‘Am I going to die? Is my baby going to die?’, those words go round and round in my head every single day. Alongside the grief and pain, I can’t get those words out of my mind. Two lives have been lost. It’s double murder.’

Their grief is compounded by the knowledge that Fawziyah was the victim of an ‘honour’ killing, murdered by a man who believed his wife’s desire to end their marriage would bring shame on his family and was willing to do whatever it took to prevent that from happening.

That it could happen to her ambitious, bright and forward-thinking daughter is, Yasmin says, a heart-breaking example of the way honour-based abuse is misunderstood, with no such thing as a ‘typical’ victim.

‘I think some people saw Fawziyah as this privately educated, clever lawyer – so how could this happen to her? But there isn’t a stereotypical woman this happens to,’ she says. ‘If this could happen to her it could happen to anyone.’

Indeed, while statistics show 2,755 honour-based abuse offences were recorded by the police in England and Wales in the year ending 2024, police acknowledge that the real figure is likely to be much higher.

What’s more, while Fawziyah had twice reported her husband’s violent and controlling behaviour to the police, they failed to tell her that she was considered a high risk case.

‘Fawziyah planned to leave her husband after their trip to Edinburgh, not knowing the evil of which he was capable,’ Yasmin says. ‘If the police had told her she was considered high risk, it might have jolted her into leaving him immediately and she would still be alive today.’

This is one reason that Yasmin, 56, is speaking out today, in the wake of a new Government pledge to halve violence against women and girls, with a new legal definition of ‘honour’-based abuse and a fresh set of guidelines to help police and social workers better support victims.

It is, of course, too late for Fawziyah, and for her parents who, as Yasmin puts it, are serving a ‘life sentence without parole’. ‘Fawziyah’s loss has destroyed us to the core,’ she says quietly.

Nonetheless, she welcomes the chance to shine a spotlight on what she calls the ‘hidden epidemic’ of honour-based violence. ‘Ever since this horrific tragedy, I have been inundated with messages from people that are going through similar atrocities,’ Yasmin says. ‘I fervently hope people can be spared our terrible grief.’

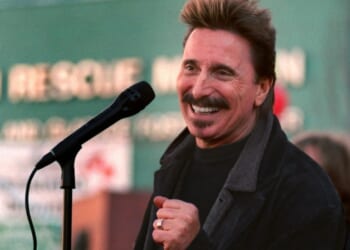

Kashif Anwar was jailed for a minimum of 20 years in 2023

Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh, with the area where Fawziyah fell highlighted by arrows

Four years on, that grief remains etched into Yasmin’s face. She has been unable to return to her job as a clerical officer, and says some days her pain is so crippling she cannot get out of bed.

Yet her face lights up as she recalls the arrival of Fawziyah in 1989, three years after Yasmin’s marriage to husband Mohammed, a restaurant worker.

‘From the moment she was born she was such a happy soul,’ says Yasmin.

Aged just eight, Fawziyah declared her intentions to become a lawyer, and after excelling at her private girls’ school, she embarked on a law degree at Sheffield University, joining a law firm in her native Leeds after law school.

‘They were so impressed by her that she got the newcomers’ award,’ Yasmin recalls. Yasmin describes how her daughter expanded her parents’ horizons, booking theatre and restaurant trips and holidays all over the world.

Fawziyah met Anwar in 2020 when accompanying her mother to the Leeds opticians where the then-trainee optometrist was working as an optical assistant.

She clearly made an impression; after running into her several days later, they exchanged numbers and started to get to know one another along with their families.

‘He told her she was the kind of girl he’d like to marry but Fawziyah laughed it off,’ her mother recalls. ‘She wasn’t the type to be starry eyed.’

The relationship quickly became serious, with Yasmin reflecting grimly on how she and Mohammed were initially impressed by what they saw as a ‘normal, charming young man’.

‘Yes, he was opinionated and a bit loud, but I thought it was a case of what you see is what you get,’ she says. ‘His parents also came across as decent, kind people who genuinely seemed to care about Fawziyah.’

And so, when the couple announced their intention to marry, her parents were thrilled.

The ceremony, an intimate affair due to Covid restrictions, was booked for December 2020 at their local mosque, and Fawziyah seemed genuinely happy.

‘I do think she loved him very much,’ says Yasmin.

Yet today, she believes that Anwar’s mask slipped the moment Fawziyah became his wife and moved into his family home in Leeds.

‘He didn’t have to pretend any more,’ she says. ‘I believe he was jealous and insecure, and all the things he claimed to love about her – her intelligence and independence – became a source of resentment for him.’

Certainly, Anwar started isolating his wife immediately, inducing her to come off social media and blocking male members of her family on the phone. He also transferred £12,000 from her bank account to his own.

Yet the first Yasmin learned of Anwar’s coercive control was when her daughter visited during Ramadan four months after their wedding and she overheard him hurling abuse down the phone.

Only later, during court proceedings, did Yasmin learn the words spoken to her daughter. ‘Who the f*** do you think you are?’ he screamed in one. ‘You’re a disease in everyone’s life. The sooner you’re dead or the sooner you’re out of my life the better.’

In another, he screamed at her about being like a ‘British woman’, by which he meant independent. ‘He hated the fact she was financially secure and had her own opinions,’ says Yasmin.

The tone of those calls – and her daughter’s tears – was enough for Yasmin to insist Fawziyah call the police, although it was only as she accompanied her daughter during her subsequent interview with a detective that she learned Anwar had also punched her daughter’s face through a pillow. Fawziyah asked the police to put her complaint on record, anxious to get back the £12,000 her husband had taken, which she believed would be made more difficult if he was arrested.

‘I wanted her to come back home right away but she was determined to get back the money she had worked so hard for,’ says Yasmin.

Farah Siddiq, from AMINA The Muslim Women’s Resource Centre, speaks during a vigil being held in honour of Fawziyah

A family member wears a badge in memory of Fawziyah outside the High Court in Edinburgh

The police told Fawziyah she was considered medium risk although, after her death, Yasmin later learned that just a week later they had reassessed her case as high risk.

‘That was never communicated to her,’ says Yasmin. ‘If they had, she might have left straight away.’

Shortly afterwards, Fawziyah discovered she was pregnant.

‘She was happy about the baby and it strengthened her resolve to leave him,’ Yasmin says.

Only during Anwar’s trial did Yasmin learn that while her daughter had been hospitalised during her pregnancy for an infection, she had been abused by her husband in front of other patients; a witness testified how she overheard Anwar telling his ‘b****’ wife he hoped she died in childbirth and blaming her for ‘bringing out this side of him’.

This, together with another incident in which Anwar forcibly dragged his wife into a car, led Fawziyah to once more report her husband to the police.

This time, she did want him to be arrested – but asked the police to wait until she had returned from a trip to Edinburgh and enacted her plan to leave.

‘Again, police failed to communicate that she was now a high risk case,’ Yasmin says. ‘If they had underlined the seriousness of her situation, she might not have gone to Edinburgh with him three days later.’

The Independent Office for Police Conduct are now investigating complaints made by the Javeds into the conduct of the West Yorkshire force.

A spokesman for West Yorkshire Police said: ‘Our sympathies go out to Fawziyah’s family after the tragic loss they have suffered.

‘The circumstances prior to her murder, including the reports of domestic abuse she made to West Yorkshire Police, are the subject of an ongoing Domestic Homicide Review led by the Safer Leeds community safety partnership.’

They added that the review will look to ‘identify any lessons to be learned about the way in which agencies work to safeguard victims of domestic abuse’.

Yasmin had confided in her daughter of her own anxieties over the trip, which was booked by Anwar. ‘She told me she knew what she was doing. Except she had no idea of the evil she was up against.’

Yasmin says Fawziyah intended to leave her husband on their return and while she will never know if her daughter revealed her immediate intentions to him, she believes Anwar had guessed. Either way, on the night of her death, guests in a neighbouring room at their hotel heard ‘a lot of shouting’ from their room.

Yasmin’s last communication with Fawziyah came around 7pm, when her daughter told her she and Anwar were taking a walk.

When police arrived at their doorstep with news of the tragedy, along with the horror of Fawziyah’s death, her grieving parents also had to confront the fact that Anwar had been arrested for her murder.

‘From that first moment he insisted she had slipped,’ Yasmin says. ‘His family were telling people the police had stitched him up. His parents have not once contacted us to express their condolences. Our daughter lived under their roof and they said they would look after her, but she came back in a body bag.’

Delays due to the pandemic meant it took 19 months for Anwar’s case to come to trial, at which the Javeds set eyes on their daughter’s killer for the first time since her death.

Today, Yasmin recalls the ‘horror’ of seeing Anwar’s mother blowing him kisses in the dock –and the stress of giving her own testimony in court about her daughter’s relationship

The trial allowed the Javeds to learn the full scope of Anwar’s callous behaviour.

After pushing his wife from the clifftop, he did not dial 999 but telephoned his father, in a call lasting a minute. Shouting down to walkers who had come across barely-conscious Fawziyah on the rocks below, he asked not if she was OK, but whether she was alive.

‘He was panicking, because of course he couldn’t guarantee that he’d killed her,’ says Yasmin.

As well he might; with her last breaths, Fawziyah told both the first person to find her and the first police officer on the scene that her husband had pushed her.

That, along with Fawziyah’s careful record of the abuse meted out towards her, was enough to convince the jury, who convicted Anwar of murder. Sentencing him to life and ordering him to serve a minimum of 20 years, judge Lord Becket called it a ‘wicked crime’.

It is justice of a sort, although as Yasmin points out, no sentence will ever compensate for her and her husband’s loss. ‘I cannot even articulate what we are going through on a daily basis. It’s destroyed us.

‘Our daughter was at the peak of her life. She was about to start a new job, she was going to come home to us and was looking forward to becoming a mother. She had a whole life ahead of her. How can you ever get over that being snatched away?’

Even today, Anwar continues to try to exert his own form of warped control from behind bars, refusing to allow her grieving parents to collect her remaining possessions.

‘When your child is brutally murdered with their unborn baby, time is not a great healer,’ says Yasmin. ‘People say it gets easier, but for us every year that passes is a reminder of another year she has missed.’

- Yasmin Javed has not received payment for this interview