As a child growing up in England, Adam Nicolson and his family paid little attention to the birds of their shire. His father, the writer, publisher, and politician Nigel Nicolson, was “no naturalist … always more interested in looking across a bit of country than in what it might be made of.” It is this “view-addiction” writ large that the son blames for nature’s demise and likely the “destruction of everything else.” To remedy this family trait, the younger Nicolson launches “an attempt to encounter birds, to engage with a whole and marvelous layer of life” hitherto ignored. He decides to welcome, watch, and learn from these feathered friends.

Nicolson builds a birdhouse – for himself. Hexagonal in shape, close to the woods, and big enough to sleep in, the shelter serves as “an absorbatory, a place to … dissolve, if such a thing is possible, the boundary between self and world,” he writes. This he does on a vast dairy farm in the Sussex Weald called Perch Hill where, over an extended period of time, he busies himself with dissolving into the birds’ world.

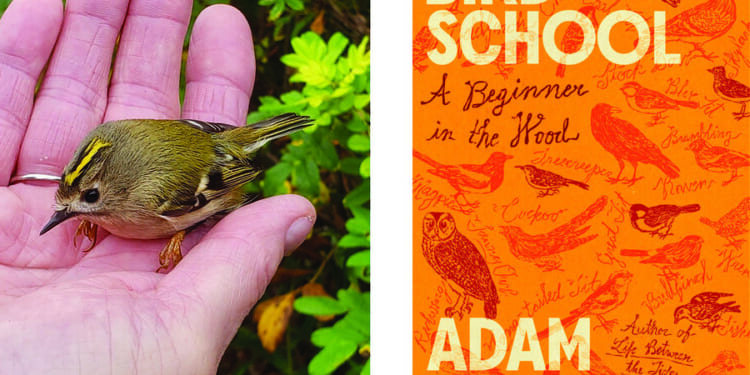

In “Bird School: A Beginner in the Wood,” Nicolson presents himself as a part-Christopher-Robin, part-Henry-David-Thoreau character taking an ornithological jaunt around the Sussex Weald. He describes how he acquired detailed knowledge of more than a dozen species of birds – and elaborates on their songs, nesting practices, feeding habits, fledging activities, and migratory routes, and even ventures to discuss their states of mind. He starts with wrens, but ends with people.

Why We Wrote This

In his new book, Adam Nicolson presents himself as a part-Christopher-Robin, part-Henry-David-Thoreau character taking an ornithological jaunt around England’s Sussex Weald.

“Bird School” is often a bit over-the-top, especially at first, as Nicolson’s literary quirks seep into the prose, bogging down the narrative with literary allusions and purple prose. But eventually Nicolson’s naturalist heart modulates the narrative, revealing singular facts and compelling anecdotes about the “extraordinary capacity” of birds that will fire the imagination of any and all avid birders.

Of the tawny owl, he writes, “It can only hunt, survive and breed through a detailed knowledge of its local world. A tawny must know the territory in all its minute and intimate particulars.” Describing ravens, he notes, “Many adults remain single, living their entire lives with the vagabond gangs.”

One of the more interesting sections involves blackbirds and a work of Beethoven. It seems that male blackbirds compose “permanently evolving and ever-complicating” songs as a way of keeping ahead of – and intimidating – their rivals. The composer, in his youth, would saunter the streets of Bonn, Germany, with ears perked and take notes; it is believed that “Grosse Fuge Op. 133” was inspired by the songs of the Bonn blackbirds.

Nicolson broaches the subject of humanity’s impact on the avian world by presenting a page-long roll call of the “regiments decimated in battle” of the “catastrophic and in many cases relentless decline” of the birds he anticipated seeing. It’s a sobering list.

In the book’s final chapter, “Perch Hill,” he addresses the ultimate question: “By feeding the birds, was I simplifying and homogenising a bird population that had already suffered more than it should? And if I was, which way should I turn?”

His answer (spoiler alert): Enable the woods to get scruffy around the edges. “Diversify, enrich, multiply, protect.”

In closing, Nicolson exhorts his readers not to be like the self-absorbed poet John Keats in his “Ode to a Nightingale”; rather, consider the nightingale “not a pet, nor a version of me or of anyone I know, but its own thing, still just here, still wild, its own apostle for its own anxious future.”