Late last week, the Trump administration announced that it would be adding a $100,000 application fee to the H-1B worker visa. While much needs to be clarified as to the details of the new fee, there are good odds it marks a generational change in the US tech labour market.

Within a day or two, certain quarters of Britain’s policymaking elite were discussing the “opportunity” offered by Trump’s looming H-1B clampdown. Encouraged by the Centre for British Progress — a think tank with close ties to big tech, the senior civil service, and Labour’s leadership — the Home Office’s new “Global Talent Taskforce” is now floating the idea of abandoning all fees for Britain’s global talent visa.

Implicit in this is a push to capture all the talent that may now be barred from work in the US with the new H-1B application fee. Currently reserved for academics and researchers that have an endorsement from a research institution, this loosened up version of the global talent visa would come with no ties to an individual employer and offer a fast-track route to permanent settlement. If used to capture putative H-1B applicants, it could potentially provide a legal mechanism for hundreds of thousands of workers with bachelor’s and master’s degrees to come to Britain.

Supporters of the H-1B system claim that it is what has propelled the radical growth of the US technology sector over the last several decades. As the claim goes, the visa has provided US companies access to top-quality talent that has allowed them to establish the innovation edge that has proven key to their global dominance. According to this logic, Britain could stand to capture this global talent pool and supercharge development of its own technology sector if the US raises the drawbridge.

The problem is that this vision of the H-1B is completely wrong. The H-1B has not served as a tool of innovation. It has served as a tool of wage suppression among US technology and knowledge workers.

85,000 H-1Bs are issued in the US every year (of which, 20,000 are reserved for holders of master’s degrees from US universities), and are intended to enable US companies to hire specialist talent. In practice, this is dominated by IT workers — as noted in Trump’s proclamation, over 65 percent of H-1Bs are issued to IT workers, primarily working in big tech or IT outsourcing firms. This is reflected in the companies requesting H-1B visas: between 2020-24, the Heritage Foundation has found that over half of H-1B visas go to Amazon (14.1 per cent), Infosys (11.7 per cent), Tata (8.4 per cent), Cognizant (6.7 per cent), Google (5.5 per cent), or Microsoft (4.5 per cent).

In the same report, the Heritage Foundation found that every occupation associated with IT and software development saw H-1B workers under-earn their US-born counterparts. For computer programmers:

-

The median H-1B earned $87,277, 17.4 per cent less than the industry median of $105,708

-

The top quartile of H-1Bs earned from $106,027, 20.9 per cent less than the industry-wide top quartile of $134,069

-

The top decile of H-1Bs earned from $125,000, 22.4 per cent less than the industry-wide top decile of $160,984

Of course, wages do not necessarily track the “innovation edge” that can be provided by H-1B labour, as is claimed by cheerleaders of the system. But this innovation edge is mythical, at least in the domain that is measurable: patents filed.

A 2014 working paper from the US National Bureau of Economic Research found that there exists no relationship between H-1B visa admittance of the amount of patents filed by industry. Rather, the measurable impact of H-1Bs is to be found in their “crowding out” of otherwise available talent: 1.5 workers for every H-1B.

It’s this crowding out effect where the true utility of H-1Bs manifest themselves: with lower-wage workers displacing higher-wage domestic workers, the H-1B significantly reduces labour costs for firms industry-wide.

Another NBER working paper from 2017, modelling 1994-2001 data, found that during this seven-year window the H-1B system reduced wages by US computer scientists by up to 5.1 per cent, while reducing employment for US computer scientists by up to 10.8 per cent. The result was an increase in the overall profit of the IT industry of up to 0.7 per cent..

The H-1B visa’s role in the US is to suppress the wages of skilled labour

Despite the claims of pro-migration think tanks, civil servants, and politicians, the H-1B visa’s goal was not to spur innovation. It is not responsible for the central innovations that have led to the dominance of the US technology sector. Rather, the H-1B visa’s role in the US is to suppress the wages of skilled labour by displacing native skilled workers and eroding their bargaining power.

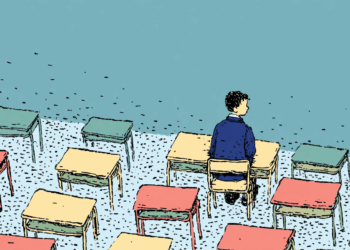

We must reject any rhetoric from pro-migrationists in favour of replicating the H-1B programme in Britain. Rather, their proposal should be treated for what it is: an assault on the livelihoods of skilled workers. With job vacancies for graduates down by over a third since 2022, an attempt to further open the floodgates of wage-suppressing skilled labour would be a generational calamity. It poses nothing short of an existential risk to Britain’s middle class.