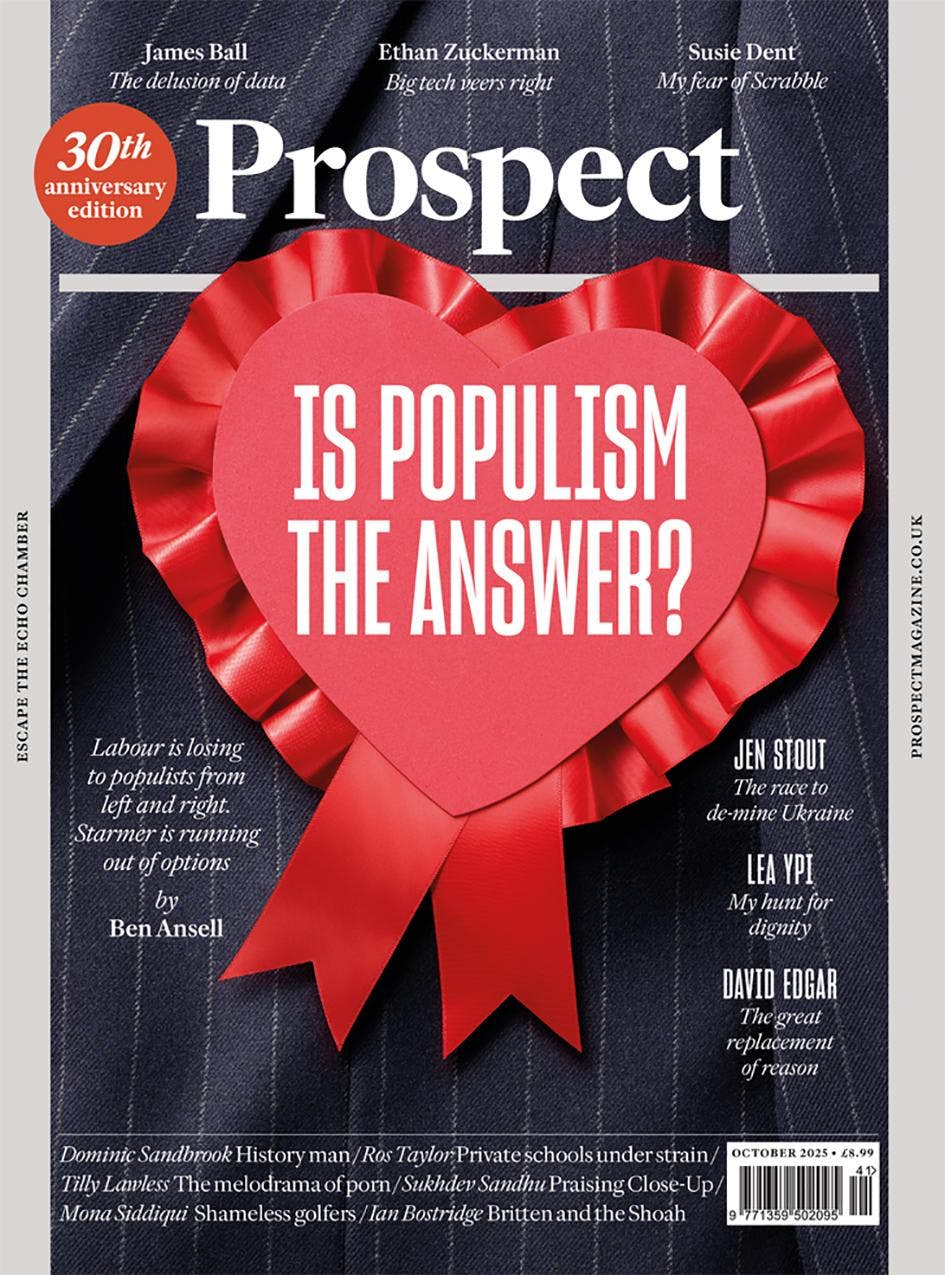

This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Fifteen years after I ceased to edit Prospect, I’m pleased to say that my creation still exists thanks to the generosity of Clive Cowdery, its low-profile owner. But under the direction of ex-Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger, its voice is seldom heard. The monthly has settled into an early middle-age, occasionally stirring itself to shake a fist at a bewildering world that no longer bends to its establishment progressivism.

My own very partial view of the magazine scene is that the energy and interest is coming overwhelmingly from the right, or at least the non-left, as in politics itself. There are the best substacks: the engaging Ed West, the optimistic Anglo-Futurists/Works in Progress cluster, the sharp and angry Pimlico Journal, (even read by Cowdery, he tells me). There is this readable and often surprising magazine, described as “dyspeptic” in a Prospect piece on who is funding Reform, one of the few in the last year that I learned something from.

Just down the street in Westminster from Prospect’s offices sits the online success story, Unherd. Despite leaning rightwards, it does make some effort to “escape the echo chamber”, Prospect’s marketing slogan which I can only assume is some sort of in-joke, given the narrowness of its political range.

UnHerd editor Sally Chatterton has discovered or nurtured new writers, avoided over-reliance on the clickbait contrarianism of a Douglas Murray or Peter Hitchens and found space for prominent figures of the left such as Yanis Varoufakis and Terry Eagleton. Freddie Sayers’s TV interviews are slick, intelligent and well-prepared. The now-defunct internationally-minded political podcast with Helen Thompson and Tom McTague was the most serious available. Everyone is now writing pieces about the eccentric American conservative Curtis Yarvin; Sayers first interviewed him in May 2022.

By contrast, the progressive media — the New Statesman, Prospect, podcasts including The News Agents and the Guardian — has been flat and predictable. Well, predictable may not be the right word for a Guardian group that backed Nick Clegg in 2010, swung behind Corbyn in 2017, and failed to develop the Observer or follow The Times’s successful journey into radio.

It is tempting to suggest that the cluelessness, to date, of Labour in office can be blamed partly on the torpor of its surrounding journalistic and think tank networks. Maybe too many people in that world really did believe that Labour were the good/competent people and the Tories were the bad/incompetent people, so all that was required was to change the personnel around the Cabinet table and all would be well.

It is telling that when, at the Prospect editorial meeting after the 2024 Labour landslide, someone suggested a piece on why the country still needed the Tory party the general response was that it didn’t. The magazine sneers at Farageism as representing the prejudice of the saloon bar (including in some witty portraits of leading populists) but displaying the parallel prejudice of the senior common room it has made insufficient effort to get under the skin of its appeal.

Since I vacated the editor’s chair in 2010, I have taken a different political path from today’s Prospect. But it is more than its politics, and there are several things I still appreciate about it. It continues to fly the flag for substantial essay-length writing; and in the past few months I have read several essays with profit, for example on the future of aircraft carriers and the connection between the video game industry and AI; and the “Lives” section at the back is always diverting, especially the regular bulletin from a sex worker.

The echo chamber is a problem with most political magazines, but it can sometimes be put to creative use if attached to a like-minded political project — Starmer’s Labour, for instance. Yet there was little sense of an inside track for Prospect as Labour cruised to victory. Prospect should be furious that Labour was so poorly prepared for office. But why was it not contributing more to the ideas bank? Why no essay series on how to reform the state, deal with the ballooning benefits bill in a humane way, work out how a land tax might function or find some other way of increasing income from unproductive wealth, and so on?

Cowdery might reasonably point to his other creation for such policy work: the Resolution Foundation think tank founded in 2005 to focus on the interests of those on low incomes. (Torsten Bell, the former chief executive, is one of Labour’s rising Treasury stars and other RF graduates are scattered around the top of Government.)

But he told me, in a conversation for this piece, that he does see Prospect as somewhere to float ideas, a place of sustained “thinking aloud”. It’s certainly not a place you would turn to for the sheer enjoyment of a good read about current affairs, with tight editing and silky prose, like the Spectator.

Magazine essays do not make government policy but, unlike more today-focused newspapers or blogs, they can help drum up support for original solutions to big policy problems and act as a kind of link between the informed public and politicians. There is such a thing as the “scoop of ideas” that can trigger a national debate.

Rusbridger, however, seems more interested in the messenger than the message. At Prospect, he has continued to pursue his favourite hobby of exposing the real or imagined iniquities of right-wing press barons. One such baron he placed under the microscope was Paul Marshall, the evangelical Christian owner of UnHerd, big backer of GB News and now owner of the Spectator, which is still in rude health. He accuses Marshall of claiming to be open-minded and non-tribal whilst helping to create a monocultural TV channel. The same might be said of the open-minded Cowdery and somewhat monocultural Prospect.

Marshall is currently out-gunning Cowdery, but the Prospect owner is also an investor in the new Observer and has a seat on the board of Tortoise Media which now owns the venerable Sunday as well as producing — amongst other things — the quirky, left-leaning Slow News podcast, which has indeed been slow to make an impact.

It’s too early to tell whether the Observer can provide a morale boosting impetus to the progressive/remainer/anti-populist cause, which is, after all, now running the country again. The early issues still feature old stalwarts such as Andrew Rawnsley, Will Hutton and Bill Keegan, repeating what they’ve been saying for decades.

The New Statesman, too, has a new editor in the authoritative figure of Tom McTague. But as neither he nor even less his deputy, Will Lloyd, are obviously on the left, it is likely to confirm my hunch that the drive and energy is coming from elsewhere.

Maybe that is because the centre-left has remained in command across most areas of public life, even during the 14 years of Tory rule. The progressive media is caught between defending a status quo substantially of its own creation — on, say, immigration or the growth of the welfare state — and an oppositional mentality that wants to blame the rich, or the Tories or populism, for our current failures.

Cowdery has deep pockets, which the Observer might need, and a remarkable backstory. At age nine he was one of five children taken away from their struggling mother and placed with a Christian group outside Bristol. He later became a leader of that group but one day woke to find his faith had dissolved so he left the church, and his young family, and started at the bottom of the insurance industry selling door-to-door.

He now sits somewhere close to the top of that industry and is worth hundreds of millions. But remembering his welfare-dependent start in life, he funds many charitable endeavours aside from Prospect and the Resolution Foundation.

Clive is a likeable man, full of youthful enthusiasm and curiosity, a voracious reader and collector of Soviet art. When he first became an investor in Prospect during my time, he said that he had received his university education from reading the magazine — the nicest thing that anyone ever said to me about it. Soon after I ceased being editor, replaced by Bronwen Maddox, he became the sole owner of Prospect and folded it into his Resolution charity.

As with many people, even the most cerebral, his politics come not from the head but from the entrails of his own life. When I asked him why he was on the left, he said he disliked how life chances are decided too much in the womb. But this is a dislike shared by many people not remotely on the left. He also seems quite blinkered about how narrowly parti pris Prospect has become, citing contributions from a couple of liberal Tories.

Cowdery remains loyal to Rusbridger but he surely cannot be happy with the lack of progress, both politically and financially — the magazine has a circulation of 40,000, mainly online, but loses even more than the £500,000 a year in my day — especially compared with his highly-regarded think tank. McTague’s New Statesman will provide new competition with a taste for Prospect-style long form journalism and a more eye-catching version of progressivism. Another attempt to revive Encounter, the original Anglo-American post-war political essay magazine, is rumoured to be in the wings.

I suspect Alan Rusbridger’s days are numbered. He’s nearly 72 and is probably looking forward to stepping down after more than four years. Next time, if there is to be one, I would like to modestly suggest that Cowdery should opt for someone who represents the more youthful, open-minded spirit of Prospect’s founding era.