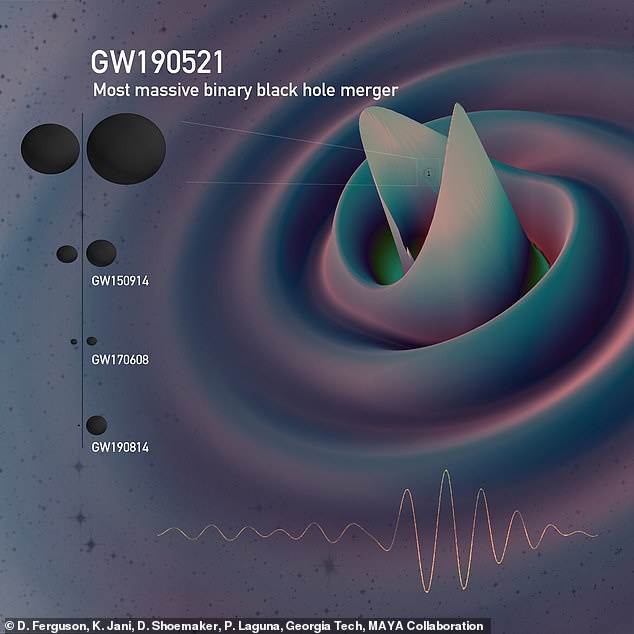

In 2019, gravitational wave detectors on Earth picked up a signal that left scientists baffled.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space and time, usually created when massive, dense objects like black holes collide.

But at less than a tenth of a second long, this sudden burst was far shorter than the drawn-out chirps normally produced by merging black holes.

Now, researchers think this strange signal, dubbed GW190521, could have arrived from a parallel universe.

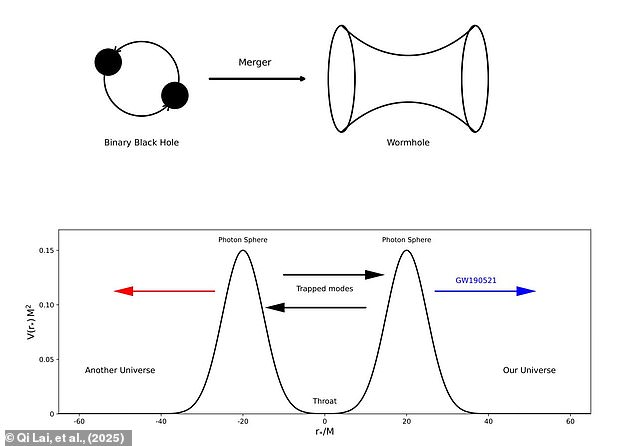

In a pre-print paper, a team led by Dr Qi Lai of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences argues that GW190521 could be an ‘echo’ of a wormhole collapsing.

If a collision of two black holes was powerful enough to create a tunnel between universes, the gravitational signal could pass down the wormhole’s throat into our cosmos.

Since the wormhole would only be open for a very short time, this would explain why GW190521 seems to cut off abruptly.

Although their modelling suggests this scenario isn’t very likely, Dr Lai says evidence cannot rule out that the signal travelled to Earth from another universe.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences say that the strange signal might have travelled to Earth from another universe (stock image)

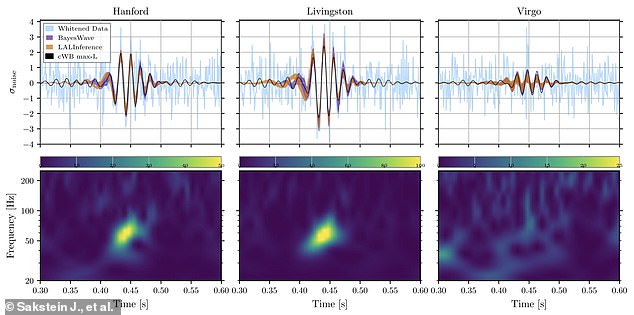

The signal, known as GW190521, was less than 10 milliseconds in length and lacked the normal rising signal associated with two black holes spiralling towards each other

The researchers modelled what this wormhole signal would look like (illustrated) and compared it to the real data from GW190521. They found that the data could not rule out a wormhole as the explanation

According to Einstein’s theory of relativity, objects with mass stretch and pull the fabric of spacetime, like weights placed on the surface of a trampoline.

One important consequence of this is that collisions between very massive objects create ripples which spread throughout the fabric of reality over enormous distances.

When pairs of black holes, known as binary black holes, spiral in towards each other, their gravitational fields interact and generate ripples of their own that get stronger as the voids grow closer.

That gives the signal produced by merging binary black holes a rising chirp-like pattern, which is a telltale sign of a black hole collision.

So far, scientists have used gravitational waves to detect about 300 collisions between binary black holes, each producing the same drawn-out chirp.

What makes GW190521 so unusual is that it is missing the rising part of the signal produced when the black holes spiral inwards.

Given that the resulting object was roughly 141 times the mass of the sun, scientists should have been able to detect this part of the signal if it occurred.

Currently, the best explanation for this unusual signal is a chance encounter between two black holes that smashed directly into one another without spiralling.

In 2019, scientists detected a burst of gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime usually caused by colliding black holes, that didn’t match any other signal previously recorded. Pictured: artist’s impression of two black holes colliding

If the collision between two black holes briefly created a wormhole, the echo of their collision would pass through the throat of the wormhole into our universe, where it would appear as a brief burst of gravitational waves

However, Dr Lai says that a wormhole in another universe is also a plausible explanation.

In their paper, Dr Lai and his co-authors write: ‘The wormhole represents such an object connecting either two separate universes or two distant regions in a single universe through a throat.’

If the merger of two black holes produced a short-lived wormhole like this, we might be able to hear a brief snippet of the chirp echoing into our own universe.

When the wormhole snaps shut, the signal would be cut off to leave a very brief burst of gravitational waves.

Dr Lai adds: ‘The ringdown signal after BBHs (binary black holes) merged in another universe can pass through the throat of a wormhole and be detected in our universe as a short-duration echo pulse.’

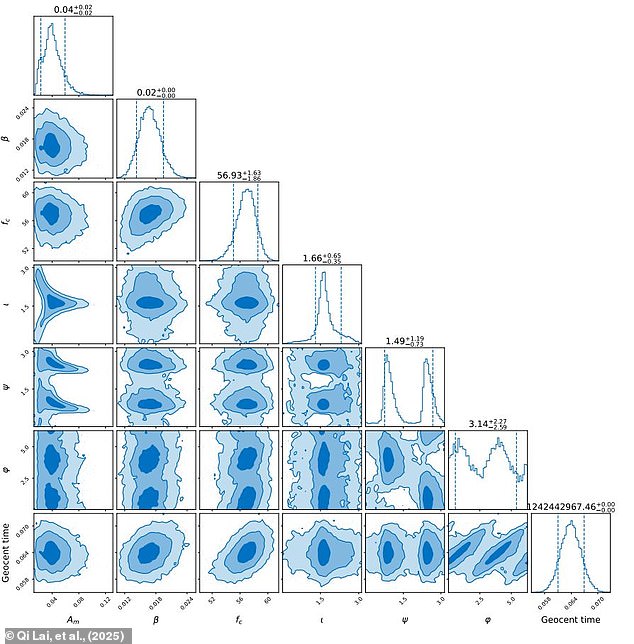

Dr Lai and his colleagues created a mathematical model of what this wormhole signal would look like and compared it to the data from the real GW190521 signal captured by the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors.

The researchers also created a model for a sudden collision in our own universe and compared the results.

They found that the standard collision model did fit the data better, but only just.

Currently, the best explanation for GW190521 (illustrated) is that a chance encounter between two black holes that collided suddenly without spiralling around each other. But a wormhole is still a viable explanation

That means the wormhole model is still a viable explanation for the GW190521 collision.

In their paper, the researchers write that the preference for the standard collision was ‘not significant enough to rule out the possibility that the echo-for-wormhole model is a viable hypothesis for the GW190521 event.’

If true, this would not only prove that wormholes exist but also give scientists a powerful new tool to study them.

That would allow scientists their first-ever glimpse into a universe beyond our own.