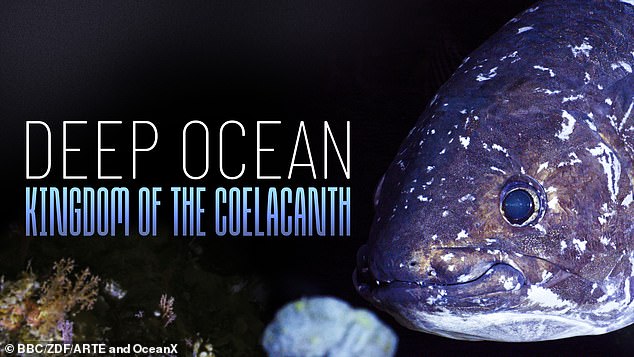

Deep Ocean: Kingdom Of The Coelacanth (BBC2)

Next time your bicycle has a flat tyre, find a coelacanth. These ‘living fossils’, dating back 400 million years to before the dawn of the dinosaurs, are an essential part of an African puncture repair kit.

The people of the Comoro islands, off the coast of Mozambique, use the scales of this ancient fish for rubbing down rubber inner tubes before glueing on a patch.

This invaluable snippet of two-wheeled repair wisdom was imparted by David Attenborough — not during his narration of the documentary Deep Ocean: Kingdom Of The Coelacanth, but more than 60 years ago in an episode of his black-and-white series Zoo Quest, where he examined a dead one in a Madagascar museum.

Until just before World War II, Western scientists knew of its existence only through fossils. They imagined it had been extinct for 70 million years. But fishermen in villages across the Indian Ocean, who regularly caught coelacanths in their nets, knew better.

They didn’t set out to catch them on purpose, Attenborough noted. These slow-moving fish can fight hard for hours, and when cooked their flesh is almost too oily to be edible. They grow to be more than four feet long and can live for a century.

The great naturalist, who will be 100 years old himself next year, was the first to film a live coelacanth, for his landmark 1979 series Life On Earth. Both that show and Zoo Quest are available on iPlayer, and are among the most important programmes ever made for the BBC.

Deep Ocean, a one-off film by a Japanese team, used a pair of bubble-car submersibles to search for coelacanths in the volcanic waters off the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Japanese scientist Dr Masamitsu Iwata and South African marine biologist Dr Kerry Sink led the expedition, both of them brimming with excitement.

Dr Sink looked terrified as her mini-sub bobbed below the surface for the first time. But she was bouncing for joy before they even found their prey. ‘There’s a jellynose!’ she gasped, pointing out a deep-sea creature that looked like a fish wearing a fascinator.

BBC2’s Deep Ocean: Kingdom Of The Coelacanth is narrated by the great David Attenborough – who was the first person to film a live coelacanth, for his landmark 1979 series Life On Earth

Once spotted, coelacanths are easy to track. The first one they sighted didn’t move for the next 36 hours. Even Dr Sink fell asleep watching it.

But when they did become mobile, every movement revealed something new to science. Instead of flicking their tails to swim, they rolled their fins, like cheerleaders waving pom-poms.

To feed, they snapped their mouths open as wide as crocodiles, thanks to a hinge at the back of their skulls. And when it was time to attract a mate, they changed colour, the way octopuses do.

All of this was accompanied not only by the erudite murmur of Sir David’s narration but with a cinematic score, too, by composer Joe Hisaishi, performed by the Tokyo Philharmonic. Thoroughly enjoyable.