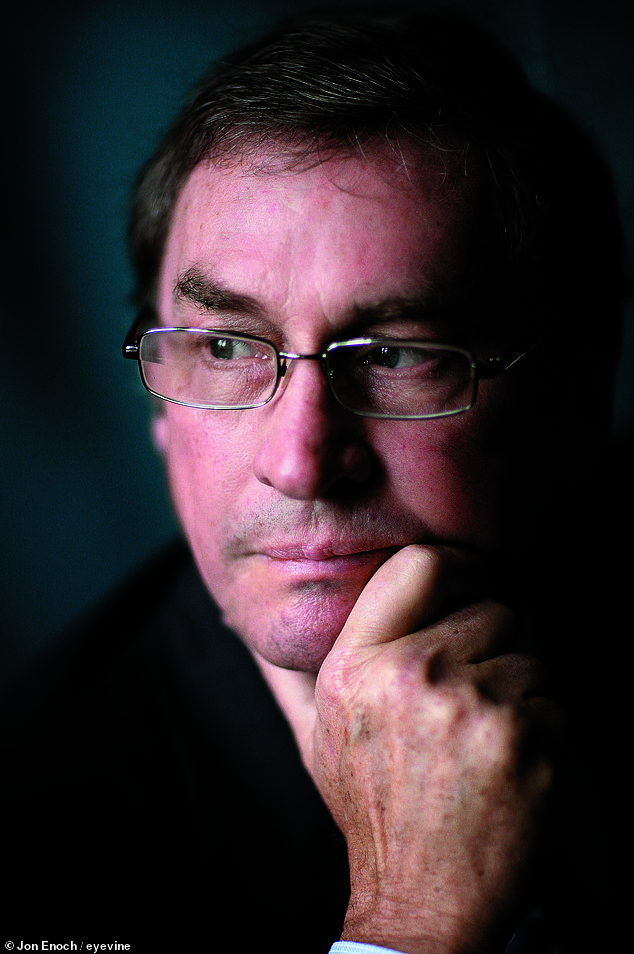

The first time Peter Mandelson resigned, I was Treasurer of a beleaguered Conservative Party that needed all the cheering up it could get.

It was December 1998 and Tony Blair‘s government, elected with a huge majority the previous year, had lost a key figure.

The Tories congratulated themselves on achieving a ‘scalp’ (in reality, it had little or nothing to do with their indignant demands to know who knew what and when about the bizarre circumstances of Mandy’s whopping secret loan from a fellow minister) and eagerly looked forward to the collapse of the New Labour project.

This duly followed – a mere decade later. Mandelson’s third departure this month came days after that of Angela Rayner as Deputy Prime Minister and was swiftly followed by the defenestration of a senior No 10 aide.

All this after the homelessness minister resigned after evicting her tenants and hiking the rent, an anti-corruption minister went over a corruption row, and the Transport Secretary left when it was revealed she had a conviction for fraud.

This is the world of politics that dominates the front pages and broadcast bulletins. It’s the world where ministers are caught out and rivals plot to topple their boss.

It’s the world of dodgy lobbying, warring factions, unwanted advances, wallpaper, affairs, expenses, Downing Street parties and contracts for cronies. It’s the kind of politics that alienates.

Then there is real politics – the kind that has a bearing on people and their lives. This is the world where people worry about crime, illegal migration, what they can afford to put in their shopping basket, whether they or their children will ever own a house, how long they will have to wait for an operation, higher taxes, and whether saying what they think is going to get them in trouble with the law.

The first time Peter Mandelson resigned, I was Treasurer of a beleaguered Conservative Party that needed all the cheering up it could get, writes Lord Ashcroft (pictured)

The Tories congratulated themselves on achieving a ‘scalp’ and eagerly looked forward to the collapse of the New Labour project. Pictured: Peter Mandelson in 2019

And this – rather than any scandal in high office – is the real source of Keir Starmer’s woes.

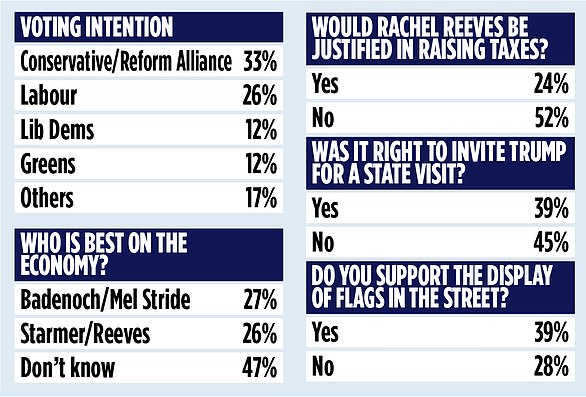

My survey asked those who voted Labour in 2024 but say they won’t do so next time why this was the case.

The biggest single reason – chosen by more than seven in ten of this group – was that ‘they haven’t got to grips with the country’s problems’. Nor do they believe the Government has a plan to do so.

Hence the second biggest reason: ‘Keir Starmer is not a good Prime Minister.’

For voters with better things to do, the Westminster game of who’s up and who’s down barely registers, except as the dull background burble of a tedious and unending soap opera.

That’s not to say it doesn’t matter – ministers should be accountable and behave themselves. Nor is it without consequence – the Tories’ obsession with their own machinations was one reason people could hardly wait to be rid of them (and one reason the party is finding it so hard to regain their attention).

But showing that he understood the difference between the two worlds is how Donald Trump managed to upend the American political establishment.

His opponents missed the point and focused on the man and his character, which is why they lost to him not once but twice.

Mandelson’s resignation came days after that of Angela Rayner (pictured at the Labour Party conference last year) as Deputy Prime Minister and was swiftly followed by the defenestration of a senior No 10 aide

Think of it as a political version of the doctrine of original sin. As far as the voters are concerned, no bunch of politicians is any more virtuous than any other.

Their eternal salvation is a matter for a higher authority, but they can earn their earthly redemption through works.

When times are hard, voters care less about process than they do about outcomes.

As my poll found, people tend to think it’s more important to get things done than to stick to the rules and conventions of politics.

This is especially true when the country faces seemingly intractable problems which successive governments couldn’t or wouldn’t – or at any rate didn’t – deal with.

Like Trump, Nigel Farage benefits from this impatience. I found a majority of all voters saying they liked Reform’s new plans to deport 600,000 illegal migrants, build secure removal centres and make unauthorised entrants ineligible for asylum.

However, only just over one in five thought the ideas could be delivered in practice.

From my focus groups, it was clear what people thought the obstacle was.

This is the world of politics that dominates the front pages. It’s the kind of politics that alienates. Then there is real politics – the kind that has a bearing on people and their lives. This – rather than any scandal in high office – is the real source of Keir Starmer’s woes

As one of our participants put it: ‘It’s a brilliant policy, but how long will it be before human rights lawyers get involved, or Nato or the UN or whoever, and say ‘you can’t do that, it contravenes human rights’?’

Tellingly, in my poll, most of those who said they liked the policies but doubted they could be delivered in practice said we should try them anyway, since any progress would be good.

As things stand, this could apply across a whole range of policy issues, from borders to welfare and from energy to crime.

If the plans look a bit rough around the edges, enough voters might think, what is there to lose?

On the face of it, this makes life more difficult for the Conservatives. Not being in a position to lecture anyone on fiscal responsibility or competent government, it is hard for them convincingly to warn against potentially reckless change with Reform.

But as she seeks a theme for her party’s conference next month, could this offer Kemi Badenoch a glimmer of opportunity?

The last government didn’t do enough to solve Britain’s problems, she must acknowledge, and it made some of them a good deal worse.

But just as there are no easy answers, neither is there anything inevitable about Britain’s decline. We can do more than rage against the way things are.

In other words: Don’t break the rules, change them. Rage is easy and change is hard, especially for a country that has forgotten how to live within its means and where too many expect the Government to do more than it can or should.

It’s a tough message, but someone has to deliver it.

Lord Ashcroft is a businessman, philanthropist, pollster and author. Find his research at LordAshcroftPolls.com.