THEY wiped our bums as babies, kissed bruised knees and steered us through the rocky teenage years to adulthood – so isn’t it only right that we return the favour and care for our parents in old age?

Not according to Tess Stimson, who says she feels “lucky” to have lost her mother and father. Here, the author and mum of two breaks the ultimate taboo to reveal why…

MY MUM Jane was a wise old bird.

“Our parents live too long, or die too soon,” she said once. “We either go when you still need us, or we become a burden. There’s no middle ground.”

Her sudden death at 59 came like a bolt out of the blue.

My father Michael’s death a decade later, at 68, reinforced the sense I’d been cheated. And yet, much as I loved them both, I’m glad they’re dead.

Don’t get me wrong: I adored my parents. I was heartbroken when they died, and I still think of them daily, often reaching for the phone before remembering there’s no one to pick up.

But as I watch my friends — the ‘sandwich generation’ — struggle to balance the needs of their ageing parents with jobs and raising kids, I’ve realised there’s a silver lining to being a 50-something orphan.

A friend of mine, Lottie*, has two elderly parents in their late eighties who live in Scotland.

She lives in London, and drives up every other week to check on them, juggling her visits with full-time work and a strained marriage.

“I love them both,” she confessed, “but sometimes I wish they’d pass away peacefully in their sleep, so I don’t have to worry about them anymore.”

It’s not that Lottie doesn’t care. But at 51, she’s long since confronted her parents’ mortality, and while she’ll grieve deeply, she’s steeled herself for the blow.

What both she and her parents fear is a long, slow decline into illness, disability or senility.

Most of their conversations revolve around their frailty, and how they’ll cope financially and emotionally. As Lottie puts it, it’s as if a sword is hanging over them all.

I know how she feels. In my 20s, I lived and worked abroad, and often fretted about something happening to my parents when I was far away.

Ironically, I’d only just moved back to London following divorce when my mother was taken ill in December 2001.

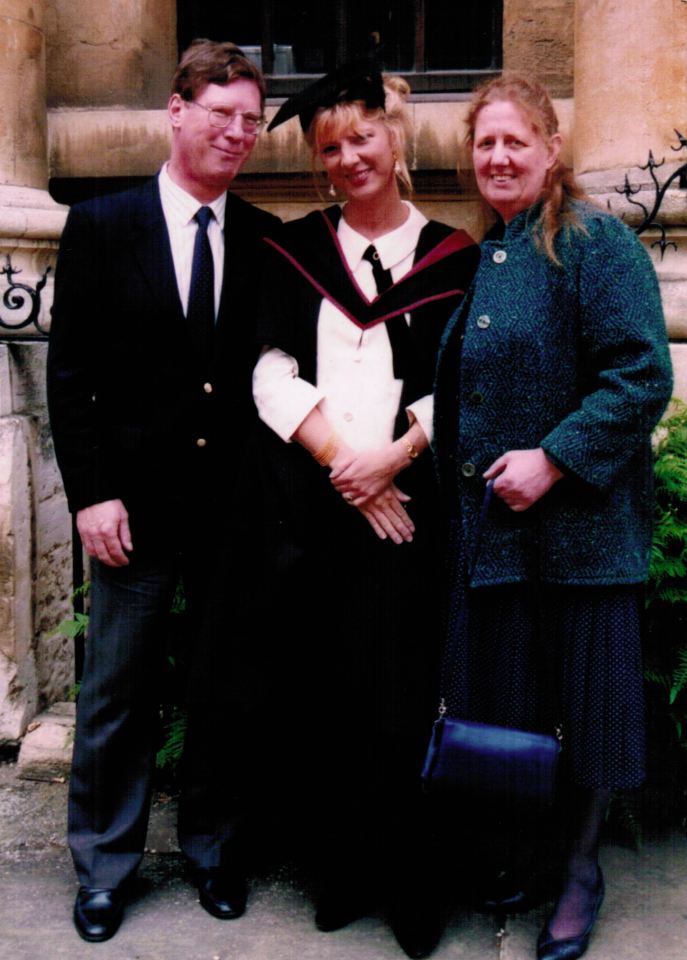

I’d spent the weekend with them at their home in Copthorne, West Sussex, joined by my two sons, Henry, then seven, and Matt, four.

Mummy and I had stayed up late that night, nattering over wine. Daddy teased us: “You talk every day on the phone,” he said. “What more is there to say?”

That next day, I headed home with the boys. I had no idea it was the last time I’d kiss her goodbye, or smile at the familiar way she urged me to ‘take care’ as she waved me off.

That night, my father called to say she’d taken ill with abdominal pains and was in hospital.

I got straight in the car, but by the time I arrived, she was in surgery. Her bowel had perforated, and she’d gone into septic shock.

She never regained consciousness and died six days later.

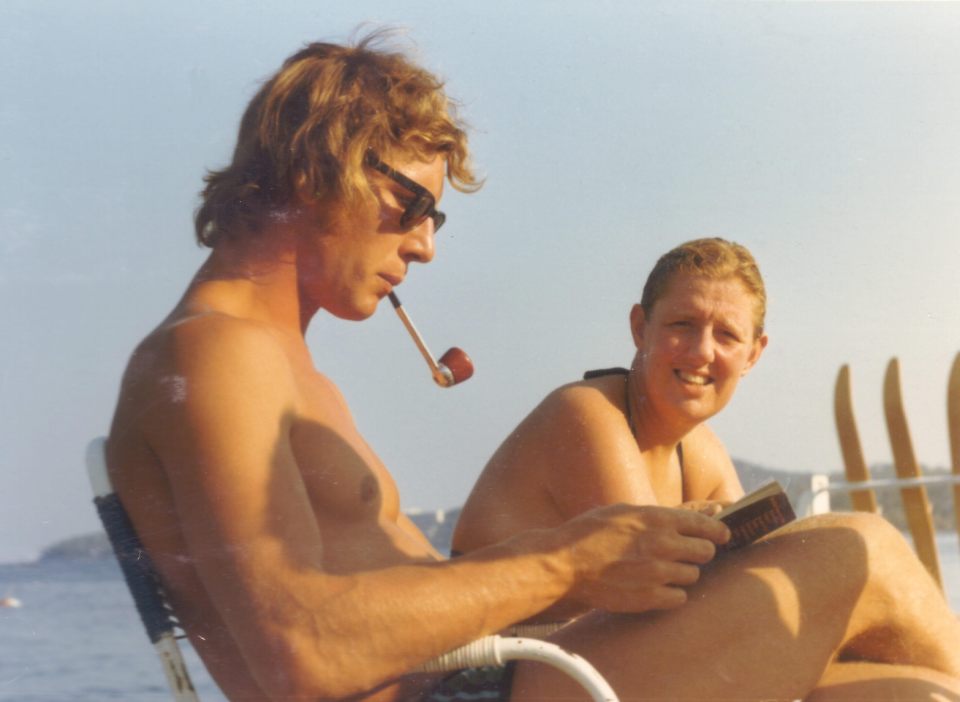

My father, then 58, was knocked sideways. They’d been married 40 years, and he didn’t know how to function without her.

I had no time to mourn; I was too busy holding Daddy together. For six months, I spent almost every minute with him, putting my life on hold.

Then, a year later, he met a wonderful woman who transformed his life and gave him hope again. I was thrilled to see him so happy.

Daddy remarried, and retired to New Zealand. I was sorry he was so far away, but we talked often on the phone.

It was on one of my trips to see him that he first spotted blood in his urine. Doctors diagnosed a bladder tumour, and were initially optimistic, but within six months, we learned it’d spread to his lungs and was terminal.

I couldn’t believe it was happening again. We all know our parents will die, and yet in our hearts somehow we think it won’t happen.

They’d become problems to be dealt with, the kind of burden my mother had always dreaded

Tess Stimson

Daddy was determined to wring every moment of pleasure from the days he had left.

He wrote his bucket list – including a helicopter ride to the Grand Canyon, and a cruise around the Galapagos Islands – and completed nearly everything.

We spent our last Christmas together in 2010. I tried to be brave, but one night I just curled up in his lap and sobbed, while he stroked my hair and told me how much he’d always loved me.

He insisted he wanted my last memory of him to be a good one, and refused to let me be at his deathbed. He waved me off at the airport, smiling.

I cried for the entire flight home, unable to believe I’d never see him again.

When he died six weeks later, I felt so alone.

All my friends still had at least one parent. But whenever we got together, where once their conversations had revolved around men, and later children, now it was all about their ageing parents: knee replacements, broken hips, forgetfulness and falls.

They’d become problems to be dealt with, the kind of burden my mother had always dreaded.

Where to seek grief support

Need professional help with grief?

You’re Not Alone

Check out these books, podcasts and apps that all expertly navigate grief…

- Griefcast: Cariad Lloyd interviews comedians on this award-winning podcast.

- The Madness Of Grief by Rev Richard Coles (£9.99, W&N): The Strictly fave writes movingly on losing his husband David to alcoholism.

- Terrible, Thanks For Asking: Podcast host Nora McInerny encourages non-celebs to share how they’re really feeling.

- Good Mourning by Sally Douglas and Imogen Carn (£14.99, Murdoch Books): A guide for people who’ve suffered sudden loss, like the authors who both lost their mums.

- Grief Works: Download this for daily meditations and expert tips.

- How To Grieve Like A Champ by Lianna Champ (£3.99, Red Door Press): A book for improving your relationship with death.

None wanted their parents to die, of course, but nor did they seem to enjoy having them around.

At least I’d escaped all that, I told myself. My parents were relatively young when they died; they hadn’t been frail.

They hadn’t lost their marbles, or stopped being themselves. I saw them because I wanted to, not out of duty; I picked up the phone because I enjoyed chatting.

I realised then I was the lucky one.

And in some ways they were lucky, too. The world isn’t kind to old people. Apart from a fortunate few, grey heads are ignored, not venerated.

My mother used to worry how they’d make their pension stretch. She dreaded ailments and poverty, mind and body falling apart, shivering by a one-bar fire. Well, she never had to deal with that.

I’m relieved I’ve never had to look into an adored face that failed to recognise me

Tess Stimson

I’m glad, too, my parents didn’t have to endure the tragic loss of my brother, who had a cardiac arrest at 40, and my sister, who died at 53 from Covid.

Losing a child is the worst thing any parent can face, and at least they were spared that.

There are times I’d give anything for a five-minute conversation with my mother, or a hug from my father.

But, for their sakes, I’m glad they didn’t have to suffer any indignity. I’m relieved I’ve never had to look into an adored face that failed to recognise me.

My parents had good lives, and good deaths at the right time – and I hope for the same.

I’ve written a detailed living will so my children never have to feel guilty about “switching me off”, and I’d do it myself if necessary.

I have no intention of submitting to a long, miserable decline. As Bette Davis said: “Old age ain’t no place for sissies.”

*Names have been changed

‘The New House’ by Tess Stimson, published by Avon.