It’s the latest parenting craze taking over TikTok—with mums proudly posting clips of their little ones and viewers gushing over their ‘chunky rolls’ and ‘cute’ features.

But this isn’t the usual battle of who has the cutest baby. These children share something far more surprising: They’re enormous.

Under the hashtag #BigBaby, the trend has drawn tens of millions of views as parents reveal their infants’ off-the-charts measurements.

In July, Oklahoma mother Maci Mugele showed off her four-month-old son Gunner, already two-and-a-half foot long and weighing 22lbs—almost half her size.

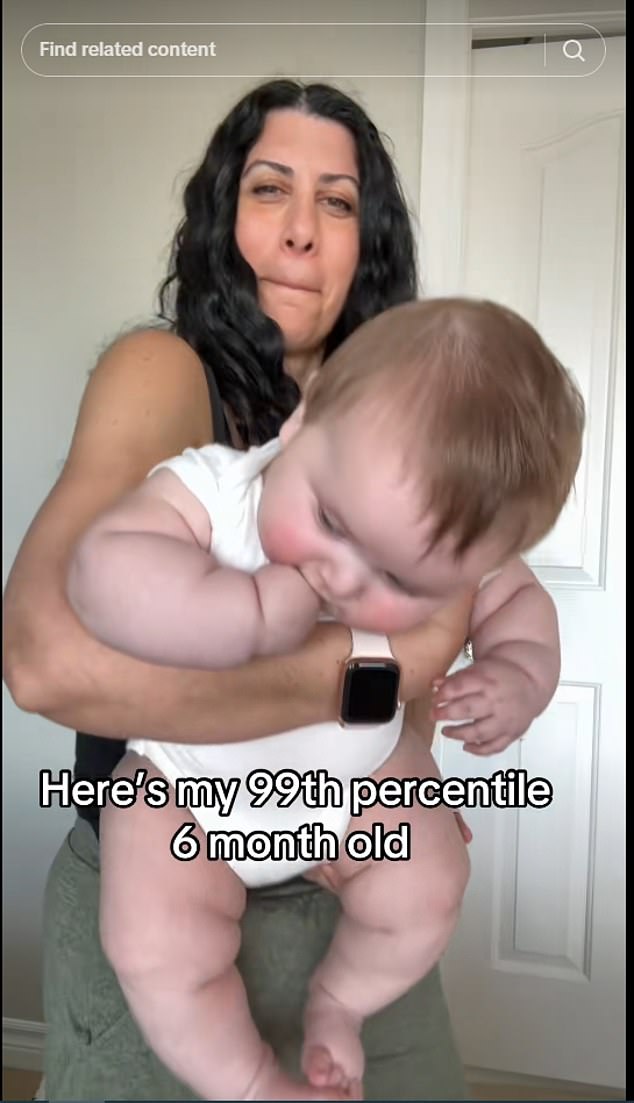

In another viral video, seen more than 44 million times, influencer Houri Hassan-Yari introduces her ’99th-percentile’ six-month-old, captioned: ‘Love my chunky boy.’

While many followers shower them with praise, others warn of health risks and even accuse parents of ‘child abuse’.

And the comment sections overflow with the same astonished questions: ‘What are you feeding him?’, ‘How tall is the father?’ — and most often, ‘How did he get out?’

Now, experts speaking to the Daily Mail warn the social media trend is part of a wider, deeply concerning phenomenon.

First-time mother Maci Mugele has faced backlash after sharing a video of her ‘giant’ 22lb baby, who’s already 2.5ft long and wears clothes for toddlers at only four months old

In a clip viewed more than 44 million times, influencer Houri Hassan-Yari introduces her ’99th-percentile’ six-month-old, captioned: ‘Love my chunky boy.’

Baby Gianna, pictured, was 12lb when she was born to Australian-based mum Shanna – and 35lb at six-months-old

25-year-old mum Chloe says her seven-month-old son is officially more than half her size

Babies are being born bigger than ever before—and doctors warn the trend could spell serious long-term health risks for both mother and child.

The condition, known as foetal macrosomia—literally ‘big body’ in Greek—refers to newborns weighing 8lb 13oz or more. Around one in ten babies in the UK falls into this category, sitting above the 90th centile for weight and height.

But alarmingly, the proportion has been creeping up for decades, according to Dr Dimitrios Siassakos, professor of obstetrics at University College London.

‘We know from national statistics that babies are getting larger,’ he said. ‘If you use the 90th centile as a cut-off, you’d normally expect 10 per cent of babies to have macrosomia.’

The reality is higher—and experts say a common but preventable pregnancy complication is likely to blame.

‘But the charter that we use was developed years ago—and babies are just getting bigger. We see so many more than 10 per cent nowadays.’

The explanation, say experts, lies in two factors. Obesity rates are rising—a known cause of macrosomia in babies is if their parents are overweight—and rates of diabetes are skyrocketing.

‘Women with untreated gestational diabetes are much more likely to have big babies,’ said Prof Siassakos.

Other mums sharing their big babies on TikTok include 22-year-old influencer Kayla (left) and mum Tyla, showing off her four-month-old

Baby Gunner (pictured) weighed 8lb 1oz and measured 19.5 inches tall when he was born on February 19

Maci, a hospital lab worker, says her baby is ‘healthy’ and doctors have reassured her that he’s just big for his age (Pictured: Maci while pregnant with Gunner)

But the 21-year-old mother was hit with backlash about Gunner’s size and negative reactions about Gunner’s weight flooded the comments, labelling it ‘child abuse’

‘But what many don’t realise is that you don’t need to be overweight to develop gestational diabetes. A significant proportion of women affected are a normal weight—or even slim.’

Doctors divide macrosomia into two main subtypes: symmetric and asymmetric.

In symmetric cases, the baby’s tummy circumference is in proportion to their length from head to tailbone, meaning they are long rather than fat. These babies are usually born to tall parents, and their size rarely causes problems.

Asymmetric macrosomia is more worrying. Here, babies are disproportionately wide around the tummy, chest and shoulders, with excess body fat at birth.

In most cases, this is the result of untreated gestational diabetes in the mother.

The condition affects around one in 20 women in the UK, according to Diabetes UK—though some estimates suggest as many as one in five.

It occurs when the body cannot make enough insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar, to meet the extra demands of pregnancy.

It can happen at any stage of pregnancy, though is more common in the second and third trimester, and usually does not cause any symptoms.

A small number of babies suffer permanent nerve injuries when their shoulders get stuck, and can be paralysed for life.

First-time mom Pamela Mann, 31, gave birth to a healthy baby girl named Paris Halo who weighed in at an impressive 13 pounds and four ounces in March of this year

Paris was taken to the NICU due to low sugar levels but was discharged later that week. ‘She’s getting a little extra love and care, but she’s doing great,’ Mann said

If left unchecked, gestational diabetes can carry serious long-term risks for both mother and child, warns Professor Amanda Sferruzzi-Perri, a foetal and placental physiology expert at the University of Cambridge.

‘Women with gestational diabetes tend to have poor glucose handling in their circulation, leading to insulin resistance,’ she said. ‘More glucose in the mother means more glucose in the baby and stimulates the foetal pancreas to release lots of insulin.’

This causes the baby to develop excess fatty tissue and even larger bones while still in the womb.

‘This is a major concern,’ Prof Sferruzzi-Perri added, ‘because we know that macrosomia can have risks for the baby.’

For mothers, bigger babies often mean longer and more complicated deliveries, with a higher chance of needing forceps or an emergency caesarean.

For babies, the dangers are even more stark. Prof Dimitrios Siassakos explains: ‘Macrosomic babies are more likely to be stillborn, and can also become stuck in the birth canal.

Their head may come out but their shoulders can become stuck—a complication known as shoulder dystocia—which can be very dangerous.’

‘Others can become asphyxiated and lose oxygen, potentially causing permanent brain damage.’

Brittany Opetaia-Halls, 29, from Brisbane , Australia, revealed she gives birth to mega babies, one who was in the 99th percentile and the other who wore clothes for a 12-month-old from day one

Brittany pictured during her second pregnancy with partner Rajan and daughter Malayisa-Maree

And after just six months Milana-Mae, born in June 2024, is a whopping 22lbs 9oz – more than 5lbs heavier than the average tot her age

As a result, many big babies are delivered by caesarean section—which now accounts for nearly half of all births in the UK.

And the problems don’t always end at birth.

Research shows that babies who are macrosomic due to their mothers’ gestational diabetes are more likely to go on to develop diabetes themselves, as well as high blood pressure and asthma.

The challenge, says Prof Dimitrios Siassakos, is spotting which babies are at risk.

‘A lot of diabetes remains undiagnosed in the UK—even during pregnancy,’ he explained.

Under current guidelines, only women with clear risk factors—such as being overweight, having a family history of diabetes, or developing the condition in a previous pregnancy—are routinely tested.

But even when screening is offered, it often misses cases. Some studies suggest standard tests pick up fewer than half.

This can have tragic consequences. Stillbirth, for example, is more common in women with undiagnosed gestational diabetes, Prof Siassakos said.

By contrast, when the condition is identified and managed, the risks of complications fall dramatically.

He added that even women at a healthy weight should remain alert to possible symptoms, such as unusual tiredness, excessive thirst or frequent urination.

‘Ongoing studies show that many women with diabetes, or poor sugar metabolism more generally, are a normal weight—or even slim or underweight,’ he said.

‘And the condition can have long-term impacts for them too.

‘Women who give birth to a macrosomic baby have a four times higher risk of developing diabetes later in life.’

Several other factors raise the odds of having a large baby.

Older mothers, and those who have already had multiple children, are more likely to be affected.

Male babies also seem to be at slightly greater risk, possibly because they are more sensitive to maternal diet, studies suggest.

The good news is that macrosomia is preventable.

‘The most effective treatment for gestational diabetes is lifestyle modification—and not anything particularly drastic,’ Prof Siassakos said.

‘Making sure you exercise regularly, and taking a common-sense approach to diet, can reduce the risk that both you and your baby will develop diabetes later in life.’