This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Ex-cons make for great podcast material. Not only do they have interesting stories but they have had years to reflect on them. Sammy “the Bull” Gravano, for example, who was John Gotti’s underboss before testifying against him, has said more about his life in the mafia than Richie Benaud said about cricket. So much for omertà.

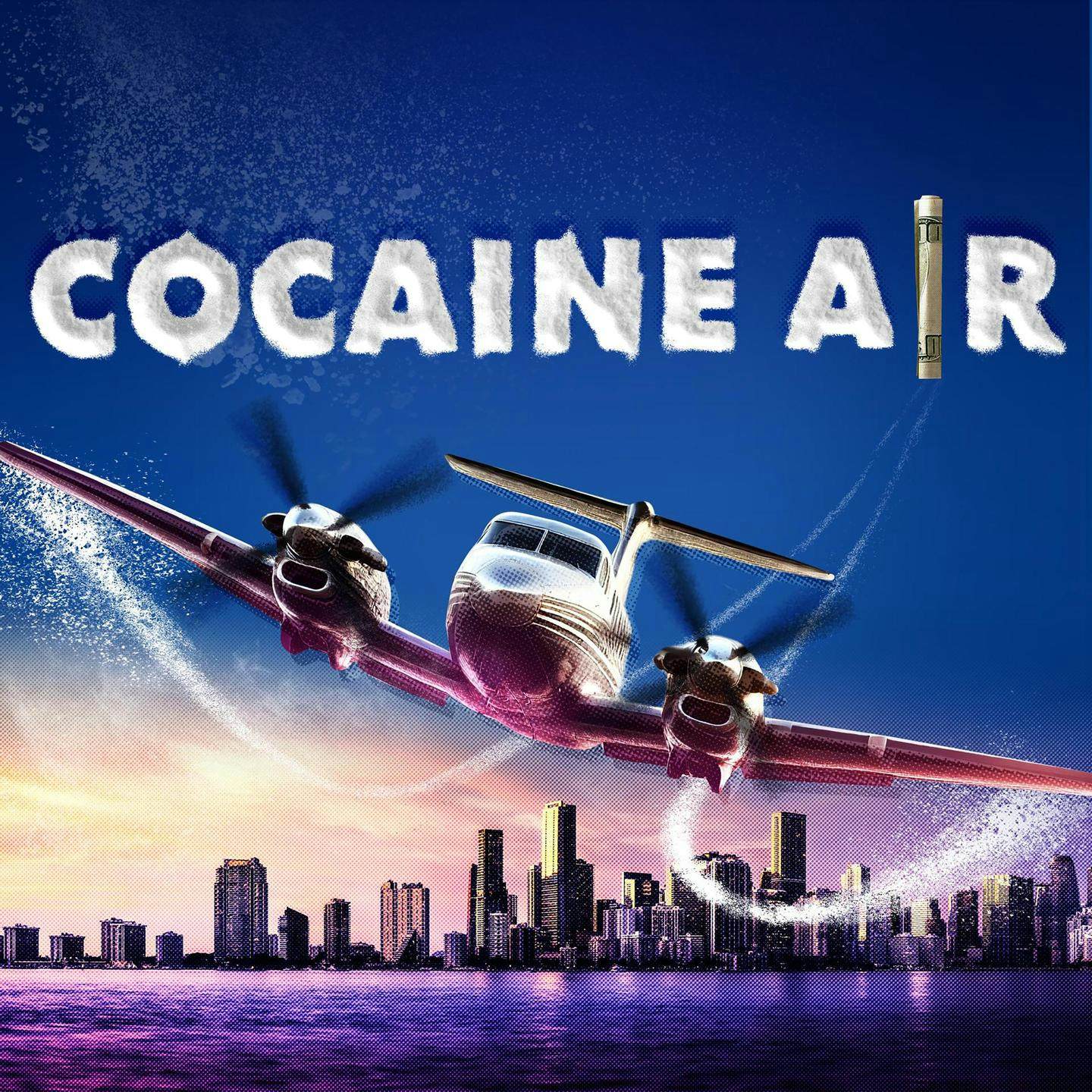

Cocaine Air, presented by the veteran journalist and commentator, Johnathan Walton, addresses the life and crimes of the prolific drug smuggler T. J. Dominguez.

Dominguez, according to Cocaine Air, was a youthful victim of ice-cold corporate scammers who turned to drug smuggling to support a family business. He took suitcases full of cash to bulk-buy marijuana — a faintly charming step in its bold amateurishness — before slowly and sloppily establishing himself in the criminal underground.

There is a farcical quality to his tales. When someone crashes into his car, for example, he has to beg them not to call the police because he is carrying his goods. Going forwards, he drives in a convoy so that other cars can catch the attention of the cops. That must have looked inconspicuous.

Dominguez graduates from smuggling marijuana to smuggling cocaine, flying it in from Columbia, and apparently making a million dollars a week. Cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar hears about him and offers a massive pay rise.

“In a bold and ballsy move,” says Walton, “TJ ambushes the head of the Bahamian [aviation administration] and hires him to look the other way.” It would appear that sheer audacity is one of the most important assets in crime. You miss 100 per cent of the shots you don’t take.

Hearing about all these illicit international antics, it is easy to forget the consequences of crime. Dominguez was enabling countless private tragedies. He was also working with a man who used mass murder to protect his cocaine empire. “I felt so bad,” says Dominguez. “I have sinned.” But he also sounds a bit proud of himself as he tells his wild stories.

Fortunately for Walton, Dominguez is a natural raconteur. His voice is reminiscent of that of Artie Lange — comedian, Howard Stern sidekick and veteran drug addict.

Whilst Lange would chuckle over tales of getting high, though, Dominguez giggles as he tells his stories of importing drugs. “I was on the plane, I was on the boat, I was on the ground,” he brags. I’m not sure if he feels like we should be admiring his work ethic. (Look out for TikTok videos depicting a day in the life of a drug smuggler.)

Money talks. Dominguez, it seems, could pay off all manner of state and private employees who simply could not earn half as much from legitimate work as from crime. He loves introducing people to his friend Benjamin — Benjamin Franklin, who features on the $100 bill — and Benjamin is a persuasive man. Dissuading people from illegally enriching themselves, as sad as it is to say, is far more remarkable than the crime itself.

Still, it is hard to understand what drove Dominguez to operate at his level. One cannot assume that an ex-con is a reliable narrator. Someone who would smuggle cocaine by the planeload might well have few scruples when it comes to honesty on podcasts (and some of his grander tales strain credulity).

But what were his motives? It doesn’t sound as if he had much fun with his money. He has a mean streak — forcing a thief to drink his blood (or “the blood of a man”) — but it doesn’t seem as if he was a stone-cold Escobaresque psychopath. It must have been an insanely stressful time.

As well as worrying about the inquiries of the feds, after all, Dominguez had to contend with the inquiries of his mother-in-law. “TJ is infinitely more scared of his family finding out that he’s a cocaine kingpin,” Walton tells us, “than the authorities finding out.”

It sounds as though Dominguez was obsessed with drug smuggling as an end in itself. His plane? A means of carrying drugs. His boats? A means of carrying drugs. His luxury car business? A front for his drug empire. Rather than the drug smuggling supporting the opulence, it seems as if the opulence supported the drug smuggling. There is something very 1980s about that.

Of course, the state caught up with Dominguez in the end and he went to jail for many years. Now, all he has are his stories. We are all familiar with the old man in the bar, wallowing in memories of his glory days. Dominguez seems much the same, except that instead of telling us about romantic conquests or his band that almost made it, he is telling us about making millions of dollars flying cocaine into the Bahamas.

It is all rather sad. After years of imprisonment — away from his mansions, and his plane, and his family — Dominguez might be asking himself if it was all a waste of time and energy.

But maybe not. Life is no morality tale. Perhaps he does maintain a sense of satisfaction. After all, few of us, if we are honest with ourselves, will have stories that could captivate a crowded bar — never mind that could be an excuse for a podcast series.