On the last day of the summer holidays, instead of stretching out on Porthmeor Beach while my seven-year-old was at art school, I was driving two-and-a-half hours from St Ives to Plymouth for a police interview over four polite tweets.

I had taken a call on my work phone weeks earlier from a Devon and Cornwall Police constable – one I never imagined I would receive – informing me that I was under criminal investigation for harassment.

Before becoming a journalist, I spent eight years teaching policing at university, so I know the justice system, including its flaws, well. Yet even I was shocked to encounter something as ridiculous as this.

When I asked why, the PC refused to say. Instead I was told to pop into the station for a ‘friendly chat’ or so-called ‘voluntary interview’. I politely declined, and the response was instant and blunt. Non-attendance meant that I’d be arrested.

This didn’t sound remotely ‘voluntary’ or ‘friendly’, but I didn’t want my daughter to see her mother led away in handcuffs, so I begrudgingly contacted a solicitor.

It actually took the police two months to disclose why I was suspected of committing a crime. Ever the annoying journalist, I steadfastly refused to attend the interview until I knew.

Officers tried to wriggle out of telling me, saying they ‘don’t normally’ like to reveal this information beforehand. In today’s Britain, you’re expected to turn up at a police station without even knowing what exactly you’re accused of.

Turns out, my tweets had reportedly caused ‘fear and distress’ to a former police sergeant. A handful of factual and polite posts on social media was apparently enough to terrify a man who spent decades dealing with violent criminals.

Rebecca Tidy-Harris was interviewed by police over four tweets she published online

I hadn’t tagged this guy and he was long since blocked from my page.

My solicitor finally emailed me a single A4 page from the police. It listed the dates I had posted four tweets, but not the tweets themselves. I trekked back through my X feed and was mystified.

The first was a factual update: ‘Former Devon + Cornwall Police officer Harry Tangye has been charged with stalking and harassment after an investigation led by West Yorkshire Police.’

As a journalist, I routinely share police news so that people find me on X and DM me their own stories, which I sell to media outlets.

That’s how my job works. It isn’t harassment. I was astonished that the police saw fit to interview me about this.

The second tweet was equally mundane, as it simply quoted and linked to a Plymouth Live article about Tangye and his partner being arrested in Newquay.

Two years ago, in a conversation with another X user, I referred to the defendant by his initials and said I believed his ‘bail had been extended to early May’. This bland remark was presented to me as the third piece of ‘evidence’.

And the final piece of ‘evidence’ was a simple selfie of me and my daughter on a beach near my sister’s house in Newquay. I hadn’t tagged or mentioned the complainant, and it’s literally one of Cornwall’s busiest beaches.

The selfie Rebecca took with her daughter on the beach, which prompted police to investigate her for ‘harassment’

Yet someone in a position of authority at Devon and Cornwall Police insisted this could amount to harassment because this ex-copper lived nearby and claimed it made him feel ‘fearful and distressed’.

If a family photo on a public beach is now harassment, then none of us is safe.

Harassment is a summary-only offence that times out after six months, but the two-month delay in disclosure meant my interview was a last-minute scramble just days before the charging deadline.

After reading the so-called evidence, I was half-tempted to leave the country for a week and let the clock run out.

But one miscalculation and I could’ve ended up in handcuffs on the runway, like Father Ted co-creator Graham Linehan, who was hauled in by armed officers over a single tweet last week.

It wasn’t worth the risk.

Everything went wrong on the morning of my interview. A lane closure on the A30 turned my 50-mile trip into a two-and-a-half-hour slog, as my phone buzzed with missed calls from the officers.

I had toothpaste on my jeans, water down my front and then my phone died while I was searching for my solicitor’s new office address. So I ended up trudging to the Magistrates’ Court to ask a scowling security guard for directions.

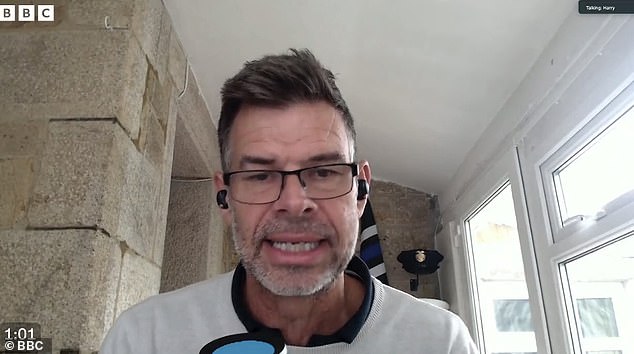

Former armed response officer Harry Tangye, pictured giving a BBC interview in 2023, denies an allegation of non-violent harassment and is due to stand trial at Bodmin Magistrates Court in November

It was far from the composed arrival I’d imagined.

When I finally arrived, two uniformed PCs were waiting with a huge video camera, tripod and laptops to record our so-called ‘friendly chat’, as if I were some dangerous criminal.

They normally patrolled the city centre, but they’d been taken off the streets to interrogate me over the three tweets, my solicitor, Jodie, whispered to me.

She was adamant that I mustn’t comment, warning me not to launch into my pre-planned speech about free speech and journalism.

Save it for another day, she told me. The quickest way out of this investigation was to keep my opinions to myself, in case the officers felt provoked or took offence.

Instead, she read aloud a short statement insisting that my tweets were perfectly legal. I was just doing my job, she explained.

The officers then asked a series of questions, at the request of a senior officer, as they presented me with an A4 sheet containing the so-called offending tweets.

I glanced at the female PC’s freshly gel-polished nails and wondered if she’d known she’d signed up to spend her career dealing with petty grievances and personal disputes.

Both interviewing officers seemed polite enough. But frankly, the situation was ludicrous.

I sat in awkward silence as they asked if I had ever had ‘relationships’ with police officers, exchanged social media messages with them or met up with them. The questions felt oddly personal and intrusive.

The pièce de résistance came when they asked if I had ever had a sexual relationship with the complainant himself.

Not only had I never dated this man, but the very suggestion was offensive and utterly irrelevant to the four tweets in question.

Without a shred of evidence, the police had decided to cast me as a hysterical, scorned woman simply for reporting on their former officer’s criminal proceedings. They’d used the oldest trick in the book to undermine my credibility, dismiss the facts and silence free speech.

The absurdity would be funny if it weren’t so serious.

I was being accused of harassing a man for reporting that he had himself been charged with harassing a woman. And the police were trying to write me off as some kind of unhinged bunny boiler.

Apparently, if a female journalist reports on a man, she must be secretly obsessed with him.

Not only had they tried to shut down free speech, but they’d turned to the most tired, overused trope to do it.

You couldn’t make it up.

The sergeant informed my solicitor that they wouldn’t be submitting the case file to the CPS and that I wouldn’t be charged.

However, it doesn’t do much to encourage women to report crime if this is how female journalists are treated.

Last week, the Met Commissioner, Sir Mark Rowley, claimed his officers’ hands were tied when it comes to instances of so-called online harassment.

He argued they were actually forced to waste time investigating petty grievances on social media instead of tackling real crime.

This is a hollow excuse designed to justify years of chasing easy targets. Let’s face it, a mother accused of sending four tweets is easier to deal with than a violent criminal.

Harassment law shouldn’t insulate people from criticism, even if they’re former police sergeants. It should protect victims of stalking and threats.

If journalists can be accused of harassment for reporting facts, Britain no longer has freedom of speech.

Police forces will never regain public trust unless they focus on real crime.

I’ll carry on reporting. If this goes unchallenged, free speech is finished for good.

A Devon and Cornwall Police spokesperson said: ‘An allegation of harassment relating to content posted online was made to the Force in March 2025.

‘A woman aged in her 30s was interviewed as a voluntary attendee on 1 September and released under investigation while enquiries continue. She has not been arrested.

‘It would not be appropriate to comment further at this time.’

- Tangye denies the allegation of non-violent harassment and is due to stand trial at Bodmin Magistrates Court in November