Once upon a time I knew Christopher Robin – the real Christopher Robin, the boy in the poems and story books written by his father, A. A. Milne.

I knew Christopher Robin in the 1980s when he was in his 60s. When he was a little boy, he was famous – the most famous little boy in the world.

When he was born in 1920, his parents, Alan and Daphne Milne, had wanted a girl. They had planned to call her Rosemary. When a son appeared, they named him Christopher Robin ‘for no particular reason’, according to his father.

‘At home,’ said Alan, ‘almost as soon as he could talk, he was known as ‘Moon’ ‘, because of the funny way he pronounced the family name of Milne.

For his first birthday, on August 21, 1921, Christopher was given a brown cuddly toy teddy bear. The bear came from Harrods (the department store in Knightsbridge) and was soon christened Winnie-the-Pooh.

The ‘Winnie’ part was in honour of a Canadian bear cub from Winnipeg who the Milnes visited at London Zoo and the rest was because, on holiday in Sussex, the family had come across a swan and decided to call it ‘Pooh’.

‘This is a very fine name for a swan,’ Alan Milne insisted, ‘because if you call him and he doesn’t come (which is a thing swans are good at), then you can pretend that you were just saying “Pooh!” to show how little you wanted him.’

According to Christopher, from his first birthday until he went away to boarding school when he was 13, his teddy bear was his ‘inseparable companion’.

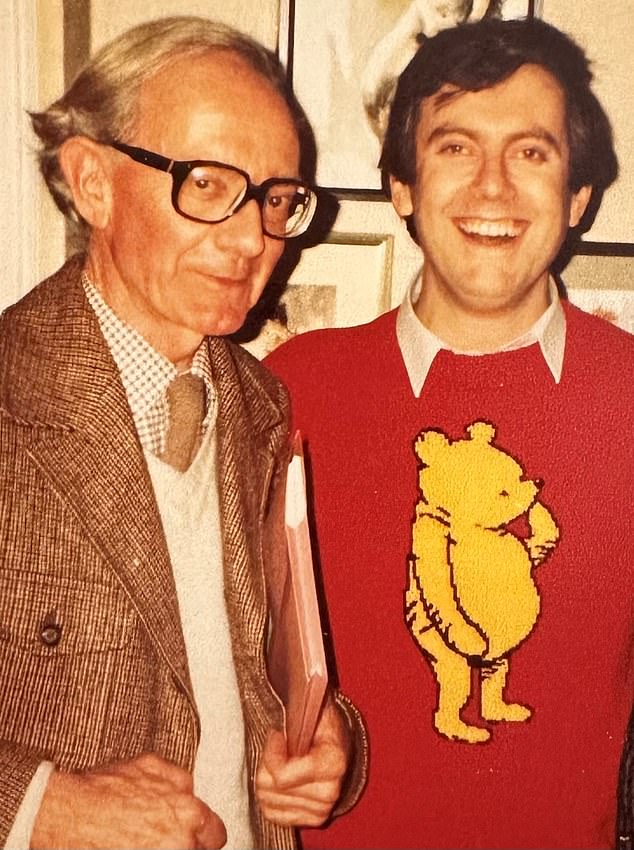

Gyles Brandreth (right) poses with Christopher Robin Milne (left) in 1986

‘I think he was called Big Bear or Edward Bear or Mr Edward at first,’ he told me. ‘But I only remember him as Pooh. He was always Pooh to me.’

Christopher was given other toys from Harrods, including a piglet and a donkey, a tiger and a kangaroo. He played with them, on his own – and with his nanny.

Her name was Olive Rand and she was the beating heart of Christopher’s childhood. He called her ‘Nou’. She was in her mid-20s when she arrived in the Milne household.

‘She had me when I was very young,’ said Christopher. ‘I was all hers and remained all hers until the age of nine. Other people hovered around the edges, but they meant little. My total loyalty was to her.’

She was a traditional English nanny: she wore a grey nurse’s uniform, with starched white collar and cuffs, a white nurse’s cap indoors and a veil when out. She was devoted to Christopher and he was devoted to her.

‘I can’t say I loved my parents,’ Christopher told me, ‘because I did not really know them when I was small. My life revolved around Nou – and Pooh.’

But his mother did play with him before bedtime and his father did tell him stories. According to Alan, who was a popular journalist and successful playwright before he wrote his children’s books, it was Christopher’s mother, Daphne, who gave Pooh and his friends – Eeyore and Tigger and Kanga and Roo – their individual voices. (Rabbit and Owl were A. A. Milne’s inventions.)

Christopher told me he remembered one day from his childhood in particular: ‘My mother and I were in the drawing room. The door opened and my father came in.’

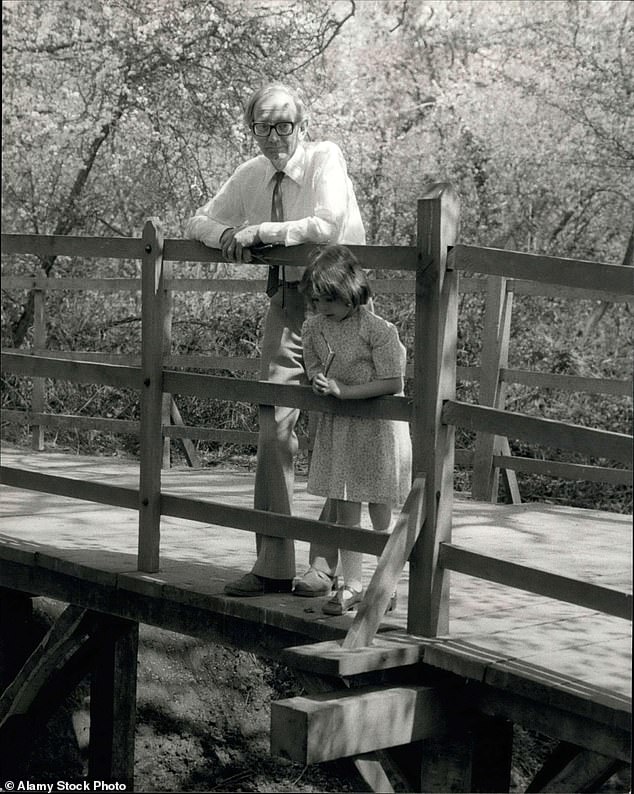

A.A Milne sits with his no less famous son Christopher Robin at their home in East Sussex

‘Have you finished it?’ asked Daphne.

‘I have,’ said Alan.

‘May we hear it?’

‘My father settled himself into his chair,’ recalled Christopher. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘we’ve had a story about the snow, and one about the rain, and one about the mist. So we ought to have one about the wind. And here it is. It’s called In Which Piglet Does A Very Grand Thing.

‘Halfway between Pooh’s house and Piglet’s house was a Thoughtful Spot…’ My mother and I, side by side on the sofa, settled ourselves comfortably, happily, excitedly, to listen.’

In the stories A. A. Milne invented for his son, all set in the forest near the house where the family lived in East Sussex, he created a wonderful world where, whatever the weather, there was fun to be had, games to be played, and lots of honey for tea. There was a bridge in the forest where Christopher went to play with his father. It was called Posingford Bridge then. It is known as Poohsticks Bridge now.

Christopher loved the stories his father told and when they were published – the first appeared in the Evening News, the Daily Mail’s London evening newspaper, on Christmas Eve in 1925, a hundred years ago, and two books followed in 1926 and 1928.

And the world loved them, too: Winnie-the-Pooh and The House At Pooh Corner were immediate international bestsellers.

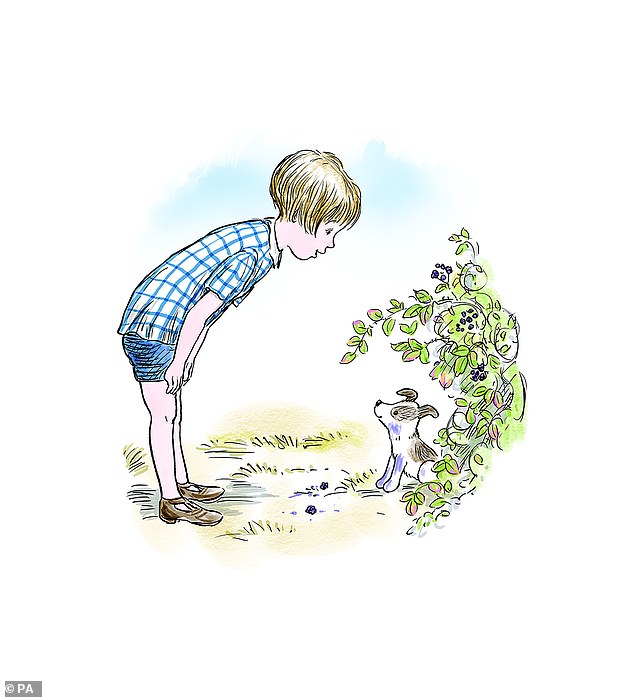

Christopher (pictured with his teddy bear Winnie the Pooh) loved the stories his father wrote

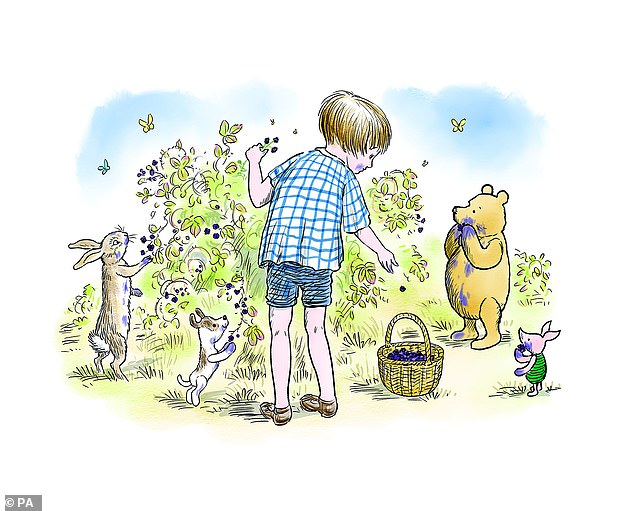

The stories A. A. Milne invented for his son were set in the forest near their house

The global success of the books – translated into more than 80 languages, including Esperanto and Latin – made the Milnes rich and Christopher Robin famous. In France they called Pooh ‘Winnie l’ourson’; in Poland he became ‘Kubus Puchatek’; in Japan ‘Kuma no Pooh-san’.

At first it was fun for all of them. Daphne enjoyed the money, Alan enjoyed the recognition, and Christopher Robin did not mind the attention that came his way. ‘At home I was just Moon, of course,’ he told me. ‘I was only Christopher Robin in public. I signed autographs. I gave interviews. I was photographed all the time.’

But then it began to go wrong.

When he was seven, young Christopher made a record for HMV. On the record he sang some of the nursery songs his father had written, including the one that begins: ‘Little boy kneels at the foot of the bed. Droops on the little hands little gold head. Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares! Christopher Robin is saying his prayers.’

Other people made recordings of that song, too. Two of the most popular were sung by Gracie Fields and Vera Lynn. And those recordings, played on the radio relentlessly, came to haunt Christopher Robin.

Christopher told me the ‘wretched’ song became ‘the bane of my life’. Aged seven he had been happy to sing it. As a teenager at boarding school, and later when he joined the Army, the song brought him ‘toe-curling, fist-clenching, lip-biting embarrassment’.

At Stowe, his public school, the other boys teased him mercilessly, he remembered, mocking and taunting him, playing the Vera Lynn record endlessly – until one day he took the record and ‘broke it into a hundred pieces and scattered it in a distant field’.

When he was sent away to boarding school he lost his nanny, Nou, and was not ‘Moon’ any more. Suddenly he was conscious of being ‘Christopher Robin’, the character from his father’s famous books, and, having once rather liked it (except when what he considered an unflattering picture appeared in the Press or an interviewer misquoted him), now he loathed it. He was teased by the other boys. His natural shyness increased; his slight stammer worsened.

The books were a global success and translated into more than 80 languages, including Esperanto and Latin

At home, in his teens, without Nou, he had become closer to his father, but he did not share his unhappiness with Alan who, in 1936, blithely wrote to tell a friend that his son was ‘the most completely modest, unspoilt, enthusiastic happy darling in the world. In short, I adore him.’

For a few years – during the 1930s, when Christopher was a teenager – they adored one another. They shared a love of cricket and mathematics, of wildlife and nature. They did not talk about ‘personal things’ much, but then, as Christopher reminded me, ‘fathers and sons didn’t in those days’.

Alan Milne needed his son’s companionship in the 1930s because he had no other children: his own parents had died by then and, in 1929, his favourite older brother, Ken, died of consumption, aged 49.

He had another older brother, Barry, but he didn’t like him or trust him. And his marriage to Daphne, once idyllic, wasn’t what it had been. The Milnes stayed together – ‘they rubbed along’ as Christopher put it – but Daphne enjoyed extended holidays in the South of France and in America, where there were rumours that she had a boyfriend. There were rumours that Alan had a girlfriend, too: a young actress who appeared in two of his plays.

Alan went on writing plays, but in the 1930s and 1940s they weren’t the West End and Broadway hits they had been in the 1920s.

A. A. Milne, once famous as a playwright, novelist and crime writer, was now only known as a children’s author – and he resented that. After his four children’s books, written between 1924 and 1928, he would not write another, however many publishers and readers pleaded with him to do so. He had lost his mojo.

And then Christopher Robin grew up and Alan lost him, too. Christopher left school and went to Cambridge University to study mathematics. When the war came in 1939, he joined the Army.

When the war ended, he went back to Cambridge, this time to study English. What was he going to do with his life? Perhaps he could be a writer.

Christopher (pictured) was ‘teased mercilessly’ at school for being the inspiration of the books

When he graduated from Cambridge, he moved to London, found himself a bedsit and sat at his typewriter: ‘I tapped away at airy nothings, sent them off, and got them back.’

He needed to earn a living. He wanted to be a writer, but his father was a writer, and a famous one. He went for job interviews and it was always the same.

‘C. R. Milne? Interesting name… Are you by any chance related to A. A. Milne? Oh my goodness, are you Christopher Robin?’

‘In pessimistic moments,’ he said, ‘when I was trudging London in search of an employer wanting to make use of such talents as I could offer, it seemed to me, almost, that my father had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son.’

He tried all sorts. He got a job at the Central Office of Information, researching statistics, drafting speeches (having studied mathematics and English, he was qualified for the job). It did not last.

He joined the John Lewis Partnership. He was there for 18 months, starting out in the lampshade department at Peter Jones in Sloane Square.

He quite liked selling lampshades: ‘I enjoyed the companionship of my fellow assistants: they were a cheerful, friendly lot.’

He liked the practical things he learned to do at John Lewis: ‘I learned how to upholster a sofa.

Alan Milne (pictured) needed his son’s companionship in the 1930s because he had no other children

I learned how to make slipcovers. I learned how to French polish, how to make curtains, how to paint straight lines… I was doing what I was doing because I had to do something, I needed to earn a living. I wasn’t very happy. I didn’t really know where my life was leading. And then I met Lesley and everything changed.’

Christopher Robin Milne met Lesley de Selincourt on Thursday February 5, 1948, at 7pm. Christopher showed me the pocket diary where he had noted it down.

He was 27, Lesley was 22. They might have met long before because they were first cousins. But Christopher’s mother, Daphne, had never liked her younger brother, Aubrey, despised Aubrey’s wife, Irene, and had never taken any interest in her brother’s daughters, Lesley and her older sister, Anne. Daphne had barely spoken to her brother in 30 years.

From the time of their wedding in 1948, Christopher and Lesley saw less and less of Alan and Daphne. After Alan’s death in 1956, they did not see Daphne at all. In 1951 Christopher and Lesley left London. ‘London was the scene of my father’s successes,’ said Christopher, by way of explanation, ‘London was the scene of my failures.’ They moved to Dartmouth in Devon and opened a bookshop.

As Christopher recalled, Daphne was amazed: ‘I would have thought,’ said my mother, who always hit the nail on the head no matter whose fingers were in the way, ‘I would have thought that this was the one thing you would have absolutely hated. I thought you didn’t like business. You certainly didn’t get on at John Lewis. And you’re going to have to meet Pooh fans all the time. Really it does seem a very odd decision.’

But for 30 years it worked wonderfully well for Christopher and Lesley. Yes, Pooh fans did make their way to the Harbour Bookshop and, if they wanted, Christopher signed copies of his father’s books for them – and did so with good grace, in return for a small donation to a local charity.

Lesley loved Christopher: she had no time for Christopher Robin – or Winnie-the-Pooh.

When once I asked Lesley what she felt about her parents-in-law, she said crisply: ‘I didn’t like them. They weren’t likeable. It’s as simple as that.’

Christopher visits Pooh Bridge in Hartfield, immortalised by his father A.A Milne

How did she find Alan? ‘Cold, closed, ungiving.’ And Daphne? ‘She loved London and New York,’ replied Lesley tartly, as though nothing more need be said. Then she added: ‘She was flighty, very actressy and superficial. She laughed a lot.’

Christopher and Lesley loved one another and they loved their only daughter, Clare, who was born in 1956, a few months after Alan’s death.

Alan and Daphne had been against the marriage because Christopher and Lesley were first cousins and they feared the consequences.

‘The one question we always used to dread,’ said Christopher, ‘was ‘And do you have any children?’ In the early days I became adept at steering the conversation onto safer ground. Now I find it better to make the matter quite plain from the start: it saves later embarrassment. ‘Yes, a daughter. She has cerebral palsy.’ There follows a momentary pause; then ‘Oh… I’m sorry to hear that.’ And then, after a few more words, we move to another subject.’

When I knew Christopher Milne in the 1980s the subject that he seemed happiest to talk about was Clare. He said that his daughter had taught him ‘a philosophy that parents don’t usually expect to learn from their children’ and he was grateful for it.

‘Once we had accepted Clare’s disability,’ he said, ‘there were plenty of other things we could be happy about, plenty to enjoy, plenty to be grateful for. And at the top of the list was her own very evident zest for life, her high spirits, her sense of fun, her cheerful acceptance of all she couldn’t do, her delight in what little she could. She set us an example.

‘We tend to think that, if someone is deprived of a blessing that we ourselves possess, their life is sadder. But in fact the man who has less than his neighbour is only unhappy if he had been hoping for more and chooses to feel jealous.’

Christopher told me that his chief delight in life had been using his hands to adapt and make everyday things for Clare: a chair, a tricycle, an unbreakable plate, a fork and spoon, a special egg whisk to help her make a cake. He had a fantasy that one day they might launch a business together: ‘C. R. Milne & Daughter – Makers of Furniture for the Disabled’.

Christopher and Lesley Milne loved their daughter and, on their own resources, would have struggled to give her the support and care she needed. Thanks to Winnie-the-Pooh they did not have to.

A. A. Milne’s four small children’s books – two Pooh books and two collections of nursery verses: 70,000 words in all, a tiny fraction of Milne’s lifetime’s output – dominated Christopher’s whole life.

And they made a small fortune that became a very large one from 1961 onwards when Walt Disney acquired the film and merchandising rights in Christopher Robin and Winnie-the-Pooh.

Christopher and Lesley wanted none of it. Christopher said: ‘To take money from my fictional self would have been the final insult.’

But the couple needed to think about Clare’s future, so eventually, and at first reluctantly, they took a share of the fortune for her.

In 2001, in a deal believed to be the biggest in British literary history, the Walt Disney organisation bought out the rights to Winnie-the-Pooh for $350 million (close to £500 million in today’s money).

Clare’s annual income from assorted royalties was already around £500,000 and this final Disney windfall was going to net her £30 million.

‘What does Clare think of all this money that’s coming to her?’ I asked Lesley at the time.

‘She’s rather vague about that sort of thing,’ said her mother. ‘She doesn’t know the difference between £1,000 and £1,000,000. That’s rather nice, don’t you think? I think that’s very nice, really very nice.’ She added: ‘Have I told you the news?’

‘No. What? Tell me.’

‘We are going to create a special charity to help disabled people. It will be called The Clare Milne Trust. Isn’t that marvellous? What do you think?’

I told her I did think it was marvellous. I still do: the Disney mega-millions surplus to Clare’s care requirements went in their entirety into a fund to help others with physical and mental disabilities. ‘A happy ending to the story,’ I said. ‘A honeypot at the end of the rainbow.’

Clare Milne died on October 27, 2012. She was 56. Her mother died two years later, on October 3, 2014, aged 89.

In 2025, a century after Winnie-the-Pooh took his first bow, the Clare Milne Trust is thriving.

To date the Trust has given away well over £12 million to help people with disabilities. ‘My dream,’ said Lesley, ‘is to know that my girl will be remembered for something that brings happiness where it is most needed.’

There was a happy ending for Christopher Robin, too. When I first met him in 1981, I was 33 and a bit Tigger-like. He was 61, spindly, slightly bent, with owlish glasses, though recognisably Christopher Robin.

He had a charming mischievous glint in his eye. Knowing something of the family story, I expected to find him reluctant to talk about either Winnie-the-Pooh or his parents. Not so. His manner was gentle, but he was immediately forthcoming.

‘We must talk about Pooh,’ he said straight away. ‘It’s been something of a love-hate relationship down the years, but it’s all right now. Believe it or not, I can now look at those four books without flinching. I’m quite fond of them really.’

When he died, aged 75, in 1996, I think he was at peace with himself and the world of Pooh. He knew that his father had created something unique: an innocent, idyllic world that, as he put it, ‘just by picking up a book, you can visit any time you like’. He smiled. ‘There’s always Pooh,’ he said, ‘there’s always Pooh and me.’

Yes, in that enchanted place on top of the forest a little boy and his bear will always be playing. Always.

Adapted from Somewhere, A Boy And A Bear by Gyles Brandreth, to be published by Michael Joseph on September 25, priced £25.

- To order a copy for £22.50 (offer valid to September 27; UK p&p free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.