Barholm Castle: The History of a Home and the Making of a Garden. Including a History of the Barholm McCulloch Family

by Janet Brennan-Inglis

(Edinburgh: Origin, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd., 2025)

ISBN: 978 1 83983 087 7 (softback)

xii + 196 pp., many col. & b&w illus.

£16-99

More years ago than I now care to remember, I lunched at the Glasgow Arts Club with my old friend, Sandy Stoddart (Professor Alexander Stoddart, DL, the distinguished Sculptor-in-Ordinary to His Majesty King Charles III in Scotland), and, after a convivial session, we descended the steps to explore the delights lurking in Cooper Hay’s antiquarian bookshop in the basement of that fine building. Within that treasure-house I found a first edition in excellent condition of The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the Twelfth to the Eighteenth Century by David MacGibbon (1831-1902) and Thomas Ross (1839-1930), published in Edinburgh by David Douglas (1823-1916) between 1887 and 1892. On the same shelf, almost twinkling with temptation, were the three volumes of the same authors’ The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Scotland from the Earliest Christian Times to the Seventeenth Century, again published by Douglas between 1896 and 1897, also in splendid nick. Even after some good-natured haggling, the eight volumes did not come cheap, but they were worth every penny, and I treasure them to this day, delighting in their wonderful illustrations, insights, and details.

The five volumes of The Castellated and Domestic Architecture, as my good friend Professor David Walker observed, in his sensitive Foreword to Dr Brennan-Inglis’s scholarly book entitled A Passion for Castles: The Story of MacGibbon and Ross and the Castles they Surveyed (published in Edinburgh by John Donald, another imprint of Birlinn Ltd., 2022, 2024), occupy “a unique place in the annals of architectural history. Although a great many of the buildings included in it have been researched and published in much greater depth since, it has never been superseded. Ever since [its] publication … its sheer comprehensiveness has ensured that when researching for an image or similarities in plan and detail in Scottish castles and tower houses it is still the first point of reference”. Quite so. Walker went on to note that “finding a complete set was almost impossible” before David Ainslie Thin’s Mercat Press reprinted them in 1971, so I counted myself as among the extremely fortunate when Cooper Hay disgorged the eight beautiful books, even though I, in my turn, had been obliged to part with quite a large sum of hard-earned cash in order to acquire them.

But I have never regretted the purchase.

Janet Brennan-Inglis has outlined many of the developments in printing technology which made such a generously illustrated project commercially viable in the latter years of Victoria’s reign, and investigated the methodologies used by the intrepid architects when surveying the structures (many of which, even then, were in a parlous state: some, unfortunately, have since been lost for ever). MacGibbon and Ross often sought help from numerous architects and historians who were kind enough to answer their calls for assistance following the appearance of the first volume. Such generosity, one suspects, would not be so readily forthcoming in these benighted times (even if one could find contemporary young people with the required skills and patience, which is unlikely, given the dismal current state of “architectural education”), and I remain astounded by the achievements of that intrepid pair in not only obtaining tremendous collaborations, but in measuring and drawing fabric when entirely dependent on railways, local hire, and bicycles, at a time before the advent of the not entirely beneficial motor-car. Brennan-Inglis has also given us much on the backgrounds of the authors and publisher. The last section of her interesting book outlined the current state of houses surveyed by the two Scotsmen so long ago, followed by information on those which have been lost, those transformed, and those at risk. The author also questioned what the future might hold for them. Given that MacGibbon and Ross expressed deep concerns for the survival of Scottish historical domestic architecture, and urged that something should be done to save much of it, many buildings nevertheless have disappeared, and the prospects still seem bleak for a great deal of Scotland’s built heritage, given widespread philistinism in government, incompetence, and greed (painfully obvious in once very handsome towns like Dumfries). One has an uncomfortable sense that so much so-called architecture today is nothing of the sort and is simply empty of anything: what is doubly tragic is that a tradition of architecture in Scotland, soundly based on the use of masonry, which made it instantly recognisable, was deliberately destroyed by the demands to use concrete as part of the totalitarian quasi-religious cult of Modernism after 1945. Why is nobody involved in Scottish Nationalism demanding something sensible, such as the revival of traditional crafts in building with stone, and the study of Scottish historical architecture?

Empty gestures are made all the more appalling when one considers what has happened in Edinburgh. The Scottish Parliament Building (1998-2004), by Enric Miralles Moya (1955-2000) and Benedetta Tagliabue (1963- ), sited at the foot of the Royal Mile, opposite Holyrood Palace, with its almost unreadable allusions to upturned boats (why boats, upturned or otherwise, anyway?) and fatuous claims that its applied “decorations” draw inspiration from the painting, The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch (c.1784 or 1790s), by Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823), cannot be said to respond to its context. It has no connection whatsoever to indigenous Scottish architecture of any period, and ignores especially the great Classical architectural legacy that was such an integral part of Edinburgh, so merely insults its context, like some loud, ill-mannered interloper at a civilised gathering. The stuck-on “decorations” have no true symbolic meaning: and that is because architects no longer know what a symbol actually is. A symbol represents what it is; an allegory represents what it is not. But that is a distinction embedded in theology, and therefore not one that will be even vaguely familiar (or welcome) today.

The obliteration of history has always been high on the agenda of Modernist architects, and the Parliament building manages to ignore history, thereby conforming to the demands of the Modernist cult. This was clearly another instance of a country with a splendid and unique heritage of great architecture, turning its back on that heritage to acquire an “iconic” building devoid of meaning and stuffed with banalities: all to be able to claim a spurious “Modernity” and perhaps by so doing conceal a queasy sense of national disappointment. Yet it is all founded on very little: as Hilton Kramer (1928-2012) observed, it has “long been known to observers of the modern movement in art that the central pattern of its æsthetic development has been that of a dialectic in which every heretical impulse has served as the prologue to a new orthodoxy”. Amen to that.

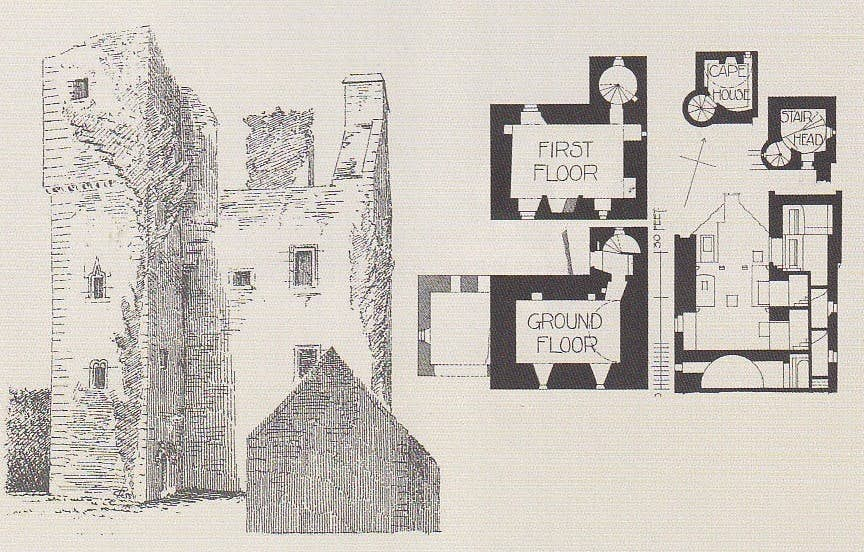

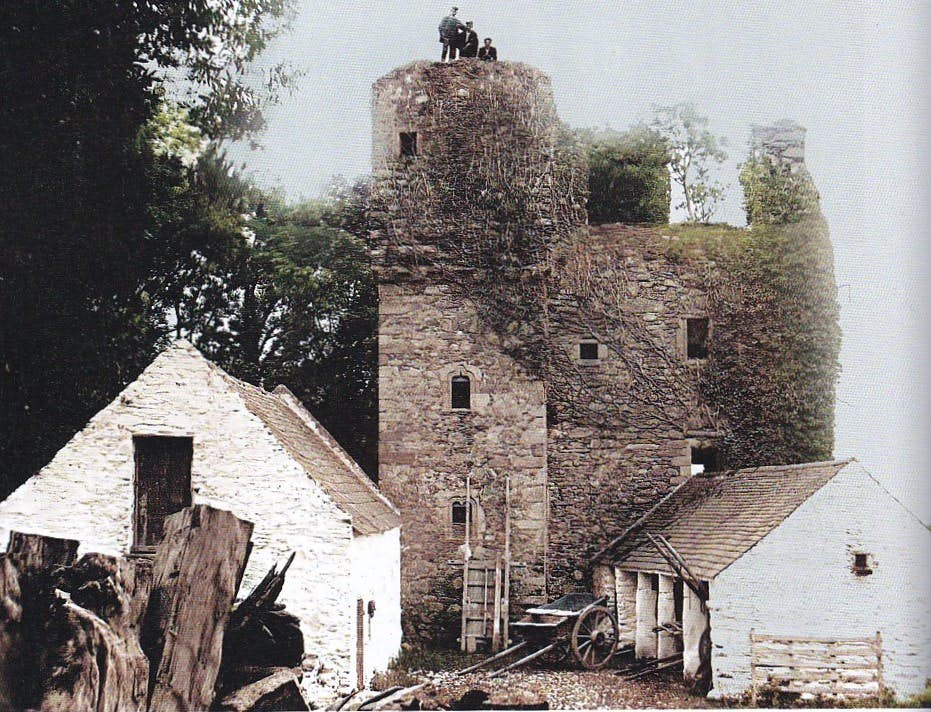

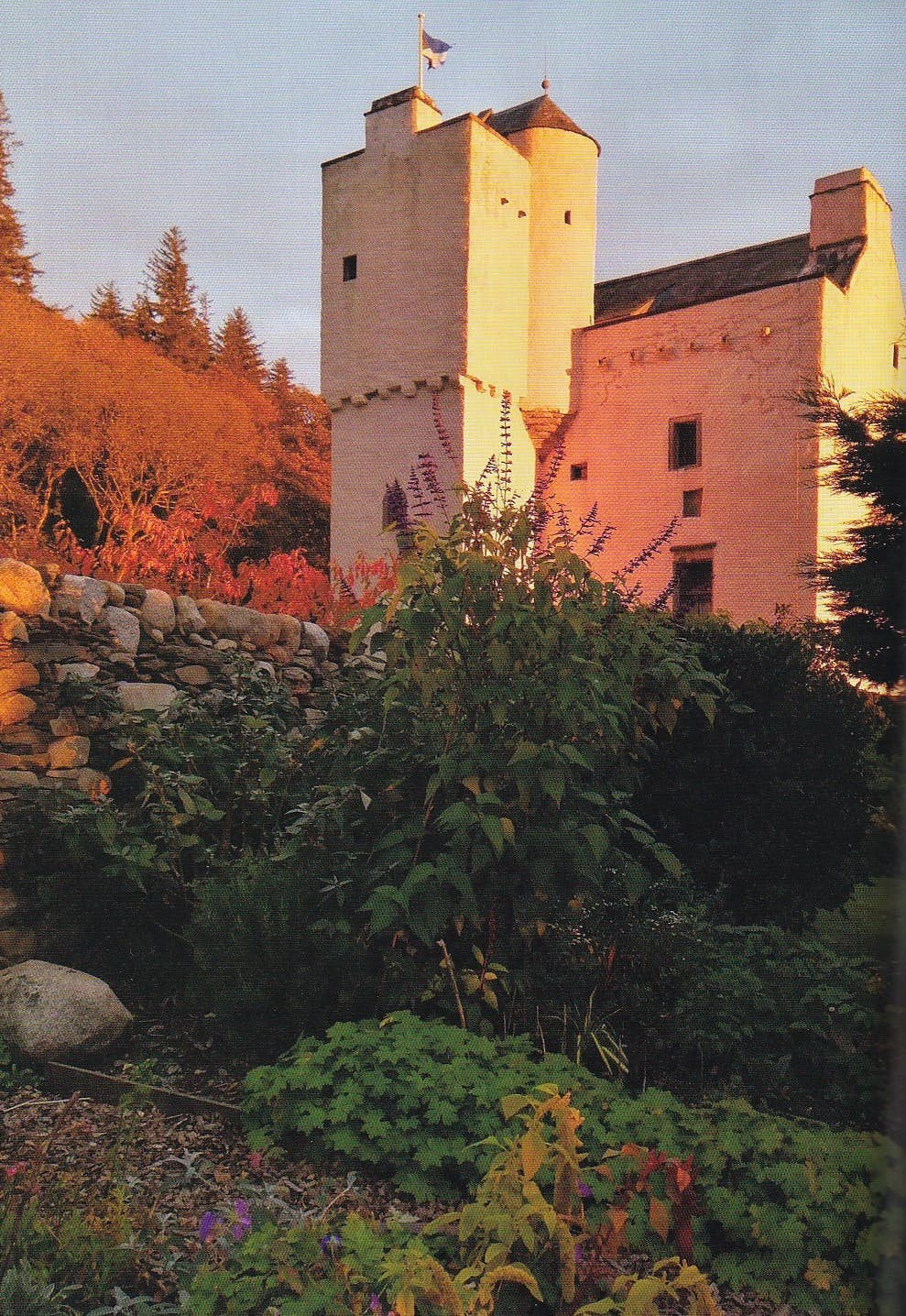

Scotland is rich in a great number of tower-houses, single buildings combining the needs for defence and living accommodation. John Gifford, in the Dumfries and Galloway volume of The Buildings of Scotland series (1996), wrote that Barholm Castle, not far from Gatehouse of Fleet, 1.3km south-east of Kirkdale, was a roofless tower-house “on a steep hillside overlooking Wigtown Bay”, a “rubble-walled four-storey L-plan, the stair jamb projecting at the north-east corner”. In the following year, 1997, Janet Brennan-Inglis and her husband, who had fallen in love with the building and its situation, attempted to purchase it, and commissioned a report from my friend, the architect Ian McKerron Begg (1925-2017), on the viability of restoring the tower-house: Begg was encouraging, but because of the onerous restrictions on the purchase, lawyers advised not to proceed. A couple of years later, however, they did manage to buy the property, and now Dr Brennan-Inglis has produced a book describing the frustrations and difficulties that attended the restoration and rehabilitation of Barholm as a home set in a fine garden.

MacGibbon & Ross recorded the structure in Volume iii of their great work: they showed in 1889 that it was ruinous and unroofed, so the deterioration since then can be imagined: the heroic works of restoration and partial rebuilding were finally completed in 2006 after harrowing delays and often ridiculous conditions imposed by Historic Scotland. Not only that, but the costs involved in trying to conserve old buildings are not insignificant: if you try to protect an old building by re-roofing it, they get you for tax; and if you restore it they charge a crippling VAT, thereby demonstrating that governmental posturings to be “green” are a complete sham, as demolishing an old building and erecting a new one involve carbon emissions contrary to the pretences of environmental responsibilities. Politicians, apologists for them, and intellectually challenged apparatchiks who do not grasp this very simple fact should be shown up for the liars and frauds they actually are.

Not far from Barholm, between the sea-shore and the A75, is an even finer tower-house, Carsluith Castle (MacG & R, iii, 513-5), but it, too is roofless, yet deserves to be protected from the weather: as an exasperated landowner in Galloway once said to me, “the maintenance of unroofed ruins is bloody expensive”. Indeed: but why is Scotland not doing more to protect and revive its great architectural heritage, instead of destroying it, not least by encouraging and permitting the erection of grotesquely expensive and crassly inappropriate structures that have no resonances at all with the nation’s traditions and history?

I had the happiness to be invited to lunch at Barholm not all that long ago, when I learned in detail of the trials and obstacles that dogged the informed and loving work needed to bring back a ruin (and one in a very parlous state) back into use as a home. I confess I was not in the least surprised, having come up against such bucranial stupidity and rigid unimaginativeness many times in my long professional life. I learned of early visits and inspections of the ruins, endless consultations about what or what not could be done with an historic building, discoveries of more and more problems, not least huge cracks in the rubble stonework as well as the “bellying” of part of a wall which necessitated its demolition and rebuilding.

The wall in question was 7 feet thick, 20 feet high, and 20 feet wide, so when the problem was discussed with the Historic Scotland inspector, it was decreed that each stone should be numbered and put back exactly in the same position. Given that rubble walls were invariably covered with harling (a rough-cast wall-finish composed of lime and aggregates [e.g. sand, small stones, crushed shells, bound with animal hair]) this pointless pedantry was eventually discarded, but only after much time and energy had been expended. Another piece of bureaucratic idiocy became apparent when the vaulted ground floor was proposed to be converted into the kitchen-dining-room, with underfloor heating. Near the centre of this space was a raised outcrop of rock, which it was proposed should be cut down to the level of the rest of the floor to enable it to be flat and allow the even laying of the underfloor pipes for the heating. The Historic Scotland inspector insisted this outcrop should remain to accord with official policies of “conservation”, thereby providing a useful obstacle to trip one up as well as make most of the room unusable. In desperation, Dr Brennan-Inglis wrote to the inspector, pointing out that if the outcrop were to remain, it would be a dangerous hazard and would prevent the room functioning as a room at all. She emphasised that while she and her husband were committed to conserving every historical detail they could, there would be many areas where constantly applying rigorous, unbendable principles of conservation would incur considerable costs or cause massive inconvenience. A kitchen where it would be impossible to stand up straight would not be very practicable. In due course, “to her credit”, the inspector gave way, and the outcrop was shaved down to enable the new room to be created and brought into use. But such petty, unintelligent demands inevitably delayed matters, and also shoved the costs ever upwards.

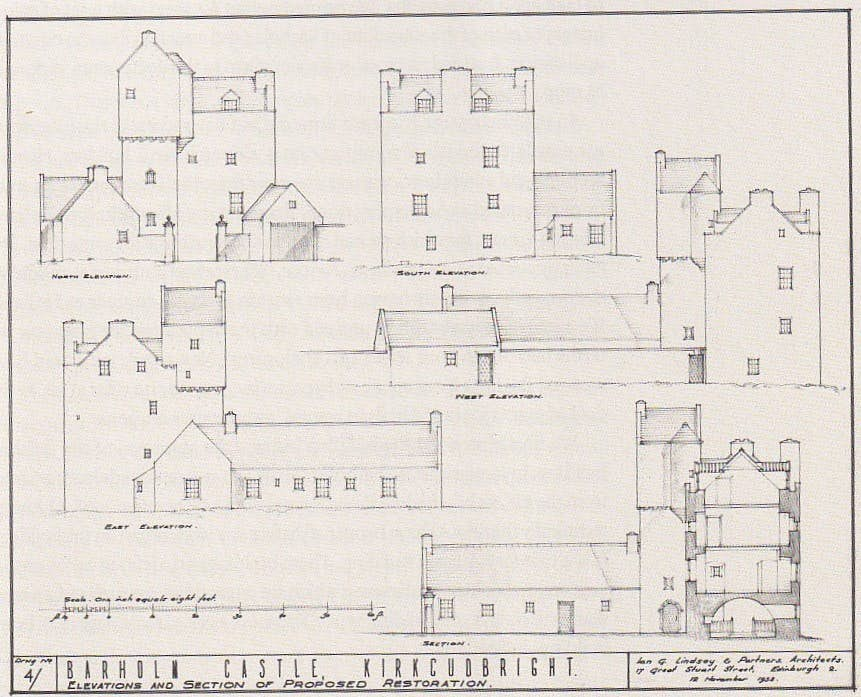

Several other enthusiasts had previously attempted to draw up sensible, sensitive plans for the building: one, of 1953, by the distinguished Scots architect, Ian Gordon Lindsay (1906-66), who carried out much excellent pioneering conservation work at Iona Abbey, Culross (Fife), and Inveraray (Argyll), was well developed, but came to nothing. Given the deliberately byzantine impediments to applying for grants, getting inspectors to move into the real world, finding contractors capable of doing the work to a suitable standard, and hoping the architect, in this case Peter Drummond, would not have the Vapours over all the mishaps, delays, frustrations, imbecilities, and incompetence of the various agencies involved, it is amazing the work was eventually completed in the teeth if so many barriers. Fortunately, Mr Drummond had had considerable experience dealing with those agencies, and so eventually everything panned out well for the building, although the costs had spiralled, largely through problems being either discovered or imposed.

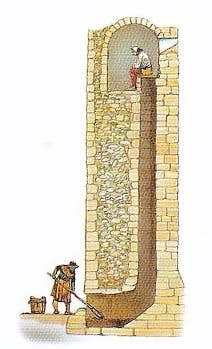

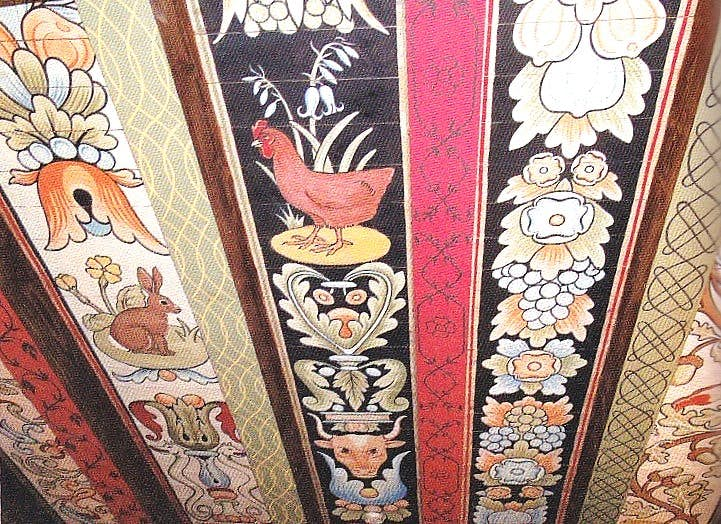

Among the features conserved at Barholm is a Garderobe (a mediæval long-drop privy or latrine): set on the second floor of the tower-house, it is associated with a moss-box set into the thickness of the wall, because moss was widely used in the past instead of the later ubiquitous lavatory-paper. But of course the ruin was really only a shell, so the entire interior had to be created, with new floors, etc. What is now the Great Hall was once a gloomy, dark, ruinous place, its walls covered in algæ, and the stone lintel over its huge fireplace broken, supported by a timber prop. Its only inhabitant was a barn-owl. The transformation has been quite wonderful, and the colourful ceiling with motifs based on those in Crathes Castle, Kincardineshire, and on images of local flora and fauna, painted by Jennifer Merredew, is an utter delight. It is a charming room in which to relax, chat, drink, and enjoy being alive.

In addition to lovingly restoring the tower-house, the intrepid owners have also created a beautiful garden, an incredibly difficult task given the situation, not least the absence of any natural water-supply: the ensemble is well captured in a watercolour by Andy McKean of 2014, and today Barholm Castle seems to bask in a new warm glow, perched on its wonderful site, a tribute to the bravery, taste, and perseverance of its owners.

In addition to the story of the building, the garden, and their resurrection from desolation and ruin, this heartwarming book includes an outline of the people connected with with Barholm, notably the McCullochs, who became Covenanters, and, like many others in Galloway, were involved in smuggling and murderous hatreds among local worthies. Two McCullochs were killed by Catholic neighbours, one was executed for his religious convictions, one became an outlaw, and yet another was wanted for homicide. Clan loyalties, greed, religious hatreds, and other factors played their parts, but it appears the McCullochs had a fearsome reputation, not just throughout Galloway, but as far away as the Isle of Man. We are reminded by Dr Brennan-Inglis of the Manxman’s Prayer:

Keep me, my good corn, and my sheep, and my bullocks

From Satan, from Sin, and those thievish McCullochs.

The Revd Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch tells me his early 19th-century forbears were tinkers in south-west Scotland, and one of his ancestors was definitely a “thug”, but his grandfather, in Edinburgh, was spotted as bright and encouraged to higher things. The Revd Professor’s grandmother, who came from grander stock, insisted on adding an extra a to the surname, hence MacCulloch. Dr Brennan-Inglis cites in her References several works on the McCullochs, but for much more on Barholm, one of the best sources is The Border Towers of Scotland 2: Their Evolution and Architecture by Alastair Michael Tivey Maxwell-Irving (1935-2024) (Stirling: The Author, 2014).

So Janet Brennan-Inglis has done wonders for Scottish castles, tower-houses, and much else: this new book of hers is a tribute to and record of a remarkable achievement.