In our exclusive first extract of Boris Becker’s unflinching account of his life in prison, serialised in the Daily Mail yesterday, the tennis star revealed his fears of being set upon by his inmates. And in today’s instalment, those inmates turn out to be a people smuggler, a cocaine kingpin and a killer from Albania…

There was a way of behaving in the locker rooms when I was playing tennis. Whenever another player was in there, you had to show your masculine side, put on a front, show no weakness. In my early days, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors led the way. They were convinced this was their locker room and nobody else’s. I saw something in them that I recognised within myself and I let it free.

On the day of the men’s singles final at Wimbledon in 1985, I remembered my manager Ion Tiriac’s advice to always take the nearest chair when you go out on court, forcing the other player to walk further to reach his.

Pushing myself into the hallway so I could stay ahead of my opponent Kevin Curren, I sat on that first chair and he stopped in front of me, looking like he wanted to tell me to f*** off. I ignored him and started taking rackets out of my bag and after a moment he turned and walked past the umpire to the far chair.

When I won that final, becoming, at 17, the youngest champion in the history of the men’s singles at Wimbledon, it was partly because I was a son of a b***h. I was in your face. You fight me and I’ll fight you. Maybe it was helpful for me as a tennis player to be like that. But it was not helpful in prison.

Whenever my cell door opened I was going out into the wild. I knew physically I couldn’t touch anyone. I would lose.

When you play professional tennis, you lose your temper a lot if you are like me, but you have to learn patience, too, writes Boris Becker

So what could I do? This was what I had to ask myself when, in May 2022, I arrived at HMP Huntercombe, a prison for foreign national men near Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire.

I was transferred there after six weeks at HMP Wandsworth, where I’d first been committed that April after being found guilty of four offences under the Insolvency Act.

At Wandsworth, I’d come under the protection of the ‘listeners’, prisoners who are the link between the inmates and the wardens and show new arrivals the ropes.

Even their trust had to be earned but once they’d realised that I wasn’t crazy, they’d started to protect me and found me a job teaching maths and English to other prisoners. And that meant being allowed out of my cell for four hours each day – two before lunch and another two in the afternoon – instead of the usual one and a half hours.

I’d assumed that such perks would transfer with me but quickly realised that at Huntercombe I would have to start again in an institution very far from the cushy open prison depicted in the German media back home.

At first, it appeared an improvement on Wandsworth, a dark and intimidating Victorian building in south-west London.

Here there were two storeys, wire fences rather than stone, green trees around and fields. I had an incongruous thought: it’s kind of beautiful round here.

Inside, it looked more modern. Not as filthy. My cell had less mould in the corners than at Wandsworth and the window was a little bigger, with a courtyard view and sun each morning.

Unfortunately it was on a wing where one of the main officers was a real p***k. A big guy who loved to say no.

He also made it difficult for me to get food, holding me back as long as possible, then telling me the kitchen was closed. When another inmate came in after me he would let them through. Sometimes he told me I could no longer pick from the options. Take that one, it’s all they have left.

It’s all about respect in prison. From the inmates, from the officials. Some of it is real and some imaginary, but it all matters. And this guard treated me like I was a piece of dirt on his shoe. In the same week, I met an officer who could not have been more different and ended up changing my life.

Andy Small was about my height and age, a lot of muscle. Light brown hair, a thick beard and wearing a blue tracksuit, which set him apart from the other officers in their black and white uniforms. He ran the gym and gave me a tour of this high-ceilinged room with a couple of rowing machines and static bikes, then a lot of free weights.

In between classic body-building posters, including one of Arnold Schwarzenegger in his posing trunks, the walls were covered with inspirational quotes.

Andy explained that they were from the Stoics, ancient Greeks whose philosophy he taught in a class at the prison. He suggested I should take it and also told me that he hoped to get me a job as an orderly in the gym, the place where everybody wanted to work.

All these hours on my own in my cell, and now someone talking to me like they knew me. Like they had plans for me. Like they cared. I felt an unfamiliar emotion kicking up again inside. It felt like… hope.

Becker defeats Kevin Curren at Wimbledon in 1985 to win the men’s singles title, aged 17

Suddenly I could see a future for me. But Monday came and nothing happened. Same routine Tuesday. On Wednesday, Andy opened my door. ‘OK Boris, they’re being difficult here with you. Trust me, you’re going to get what I told you, but you might have to wait a couple more weeks.’

Until I was granted the ‘enhanced’ status which meant I could work in the gym, I was back to it. Out briefly for lunch and that tyrant of a prison guard trampling on the small moments. Out again for dinner, and more food you didn’t want but needed to eat. One day passing and the next beginning just the same and nothing to set any of them apart.

A week in, I decided that, if the gym had to wait, I could exercise in my cell. I paced it out. Two steps wide, maybe four steps from door to window. I created the shortest lap I had ever exercised on and began walking. Half an hour clockwise, half an hour anti-clockwise.

After some sit-ups, I tried push-ups but a life of tennis is bad for the elbows when you get past your half-century so I put my books to use – Barack Obama’s memoir in my right hand and a biography of Karl Lagerfeld in my left, and bicep-curled them as if they were very well-written weights.

That’s the thing about the incredible life of a president or fashion icon. There’s a lot of words and a lot of paper and a nice heavy cover to hold them all inside. I did the whole thing twice a day. Once in the morning, once in the afternoon, as I waited for my luck to turn.

When you play professional tennis, you lose your temper a lot if you are like me, but you have to learn patience, too. I would say to myself sometimes, when I was two sets and a break down and sitting on my chair between games with my head under a towel: OK, Boris, always play until the last point.

Now I stayed with the same message as I lay on my bed, head always at the end furthest from the door, sacrificing a view of the window for the protective animal instinct of having your feet between you and anyone coming in.

The tennis star with his third wife Lilian de Carvalho Monteiro, whom he married in 2024

One day, I was offered a radio by a guy whose cell was a few doors along. I said yes. I could let a little more of the outside world in. But a radio is seldom just a radio, if the inspectors are coming calling.

I was saved by a warning shake of the head from Baby Hulk, as I called the muscled Lithuanian giant in his early 20s who shared a cell next to mine. He was serving nine years for growing marijuana and I felt he had a good heart but I saw as well how quickly the heat could rise within him. And he particularly loathed paedophiles.

Everybody did. In a place of rogues and outlaws, they were considered their own special category of moral pariahs and had to be kept apart from other inmates, hence, it was rumoured, the prison acronym nonce: Not On Normal Courtyard Exercise.

But Baby Hulk really loathed them. Hearing that a new arrival, a slight young man, had raped a little girl, he went to his cell one Saturday afternoon and borderline killed him.

He was put in solitary confinement for three weeks and when he walked back onto the wing, the inmates gave him a standing ovation. He was a hero.

Even as I hated what his victim had done, and wished I could help Baby Hulk deal with his demons, I profited from them and his celebrity. Hulk was the guy who walked with me to the showers, to the servery. The twisted respect he received came my way. No one was ever going to touch Baby Hulk, or his friends.

Waiting to be enhanced was all the harder because, for some unknown bureaucratic reason, my partner Lilian had not yet got permission to visit me in Huntercombe. So no visits, no gym time. The promise of a job with Andy and the course in Stoicism, but nothing more.

Twenty-two hours a day all alone in my cell. It can send you mad, all that time, all that silence. All that space for dark thoughts to climb into your head but I could not let them in. I’d always talk in a friendly way with the warden on the wing, not letting him see he was getting to me, but with that a**hole, it was always the same.

‘Hey, excuse me, I’ve done the time now, I should be enhanced…’

‘No, that’s not correct. You have to stay here another week.’

Finally I got the news that I was in as a gym orderly. My door would no longer be locked 22 hours a day. And I would be moving cells from the first floor down to the ground floor.

This time I was one cell from the end of the corridor and in the cell on the immediate right was a big, serious-looking guy. An air of danger about him.‘He’s called Ike,’ Baby Hulk told me when we saw him in the gym later that day. ‘Big, big drug dealer. Cocaine, the hard stuff. He was worldwide. London, Nigeria, Germany. He’s done 12 years already. Now he’s in the gym twice a day.’

Mopping the floor of the changing rooms, down on my hands and knees cleaning the toilets, I was kind of invisible. So I could watch Ike, and after a few days I began talking to him, asking about his workouts.

That was the start of a cautious trust that formed between us, and with a small guy named Shuggy, whose cell was on the other side of mine. A Sri Lankan man inside for gang violence, he liked the gym, too, but God defined his life and he prayed several times daily in front of a little altar in his cell.

On Sundays the three of us would go to the services in the church prison. What else are you going to do on your Sunday morning – take the dog for a walk, wash the car, prepare a big Sunday roast?

I was happy to do the occasional reading. I saw it as a good thing to be picked, and I thought it displayed confidence to the inmates I didn’t know, that I could get up and speak in public.

They liked the Old Testament stuff, in the main. The meaty stuff, more dramatic, more inclined to the black and white. And when I had read and Ike had read, and that part of the day was all done, all three of us would go to the showers together.

I said you couldn’t prepare a big Sunday dinner. That turned out to be wrong, because Ike began inviting me to his cell for lunch. He had no hot-plate or saucepans, no knives and forks. Just a kettle. But somehow he would cook up a feast.

He called it fufu. A West African speciality. Balls of maize, rolled in his hands and boiled until they held their shape, then dipped in a sauce of vegetables and stock and flavour. He ordered the ingredients from the canteen menu, paid for it with his wages from the laundry. I understood the honour I was being given: my neighbour, sharing his bread with me. The respect, the friendship. All the other inmates he could have eaten with, the ones who could maybe pull favours for him.

I knew he liked Diet Coke, so I bought a couple of those for him with my gym wages and hoped they were cold enough to enjoy.

The unspoken pleasure of it all. First Sundays, after church service, then sometimes Saturdays. Hanging out, talking stories, eating together.

Ike wasn’t Baby Hulk but he was a big man and muscles mattered on the wing where the allegiances and the power structures were organised along national lines.

Across the corridor from me was Alex, an Albanian drug dealer who had killed two men with a knife. Not as muscular as Ike, but strong shoulders, strong arms. You could tell from the way he held himself that if you looked him too long in the eyes, he was going to do something.

He seemed quiet. Not like a man who could stab two people in the street, but then what did that look like anyway?

Alex talked to me more when he saw Ike and Shuggy trusting me and one afternoon I asked him what he would do when he was out.

‘Boris, we are drug dealers,’ he replied. ‘When I’m out, I’m going to go back to my job. That’s what I’m going to do.’

I don’t know if he felt Huntercombe was teaching him something or not. Maybe he didn’t feel the need to change. Maybe he was just a realist. Drugs made him money; drugs bought him a car and house.

It was the same with another guy, very tall, very friendly to me and in Huntercombe because he was a people-smuggler.

‘Boris, it’s not that I needed money, I had a serious job before and everything,’ he told me. ‘But I made so much money every week and you know what, I’m going to do it again. It’s too good not to.

‘It’s a joke how much I can make. Half a million or so every month. If I make five, six million pounds a year for five years, well then I’m done.’

He gave me his whole game-plan of how he smuggled people across the Channel from France and the Netherlands to England.

He was OK about it. No moral issues. Just enjoying the money.

I listened to it all. That was where I was now. I listened and passed no judgment, focusing not on trying to change the lives of others but on what the Stoics course I’d started with Andy could teach me about my own life. A phrase Andy kept returning to was about being ‘a master of self’.

That was someone who could move past being a victim, accept responsibility, see and correct his errors. Someone who was not controlled by his inner ‘chimp’, the part of the brain which takes control of the handles when we are angry, hungry, frightened, threatened and in pretty much any other emotional situation.

I had to start making my own decisions. Who I allowed back into my life, who I didn’t. There had been a time when I had given up and let it all happen. When I thought – that’s the way it is, I can’t control it, I can’t change it.

Prison had given me the time to think about things and the Stoics had helped bring me to a new point. I was determined not to give up on it, and never to go back.

AS WE reached the last week of June, heat building in the low corridors and small rooms of Huntercombe, the start of Wimbledon came round. How strange it felt, that summer, to be so far away. Not to be driving in to the All England Club a few days early to see the old place, to meet old friends and pick up my commentary rota.

Even when it’s close to 40 years since you first stepped on to Centre Court, the snap of your serve still sounds in your head, you still feel the slide and grip of that grass under your feet. Watching it on TV felt like being away from home for Christmas, or watching your kid’s birthday party on Zoom. I was too close and too far away, all at the same time.

I didn’t know then what a special Wimbledon it would be. The connections that held me to those courts, to the white lines and dark green grandstands, and not least to Novak Djokovic, who I’d coached to two men’s singles titles at Wimbledon. We’d stayed close and, at a press conference on the first day, he told the reporters he was thinking about me.

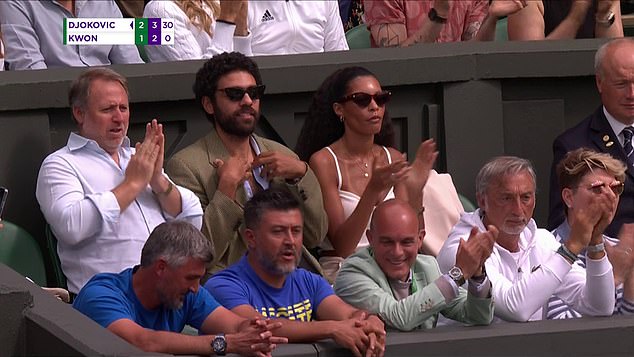

Lilian and her son Noah watch Novak Djokovic play at Wimbledon, while Becker tuned into the match from prison

‘It’s terrible,’ he said. ‘I’m just very sad that someone I know so well, and of course someone that is a legend of our sport, is going through what he’s going through. I just hope that he will stay healthy and strong.’

When I called Lilian that weekend, we talked about it. How good it felt to be remembered, when you thought everything was moving on without you.

‘This is hard on me, but it’s hard on you, just the same,’ I said. ‘You should go watch Novak at Wimbledon. Call his manager Edoardo, I’m sure he’ll get you a ticket.’

Of course Edoardo said yes.

‘I’ll get you two tickets,’ he told Lilian. ‘There’s just one condition: if Novak wins this match, you’ll have to come every time.’ I liked this rule. I’d experienced it, too, when I was part of his team.

That Monday afternoon, I was on orderly duties in the gym where the tennis was on the TV. Watching Novak winning the first set against South Korea’s Kwon Soon-woo, I waited for the camera to cut to the players’ box and there was Lilian and my 28-year-old son Noah, wearing my jacket, maybe even my shirt… definitely my shoes.

I couldn’t hide it now. I was looking at the screen and smiling.

Since this was prison, the talk around me didn’t cut corners. ‘f***, you’ve got a hot chick, how did you do it?’

‘Hidden talents, my friends, hidden talents.’

Then the other comments: ‘That’s your son? The black kid?’

A different sort of respect, now. OK, so that’s how your family is… A kind of new acceptance and recognition from all the black inmates.

Conversations were happening now that could not have taken place before. Inmates I hadn’t spoken to coming up to me in the gym, where the TV was now always tuned to Wimbledon in the afternoons.

In Novak’s ensuing matches, in the tight seconds where contests turn, I could sometimes pretend to myself that I wasn’t in a prison gym, mopping floors, scrubbing toilet seats.

I could feel myself in the commentary box at the back of Centre Court, headphones on, microphone in my hand. I would find myself commentating, sometimes inside my head, sometimes to the inmates who would come stand at my shoulder and ask me questions. Telling them, even when Novak was two sets down and Jannik Sinner looked to be away, that Novak could still win.

All these thoughts focused on a distant place, such an escape for those hours. I felt happier than I’d felt in months, but sadder, too. Seeing my partner and my son, close but not close enough; watching the player I had coached to Grand Slam titles aiming for another.

Becker with Novak Djokovic, who he coached, in 2016

Emotions I’d kept tucked away, coming up on my blind side. Tears, sometimes just below the surface, sometimes bursting through.

Prison never truly leaves you alone for long. It’s the system that rules you, and any brief respite you find will never last as long as you might hope.

Thursday, July 7: The women’s semi-finals, Elena Rybakina against Simona Halep, Ons Jabeur versus Tatjana Maria. I wanted to watch, but the guards had another idea.

You could see how it made sense to them: they wanted a basic tennis court marked out in the exercise area, so who else would you order to paint the lines than the guy who spent his life sprinting around them? I went out into the sunshine and took my brush and marked it all out and painted.

On the afternoon of the men’s final, I was watching on the small TV in my cell. Waiting to see Lilian on TV, waiting for Novak to step onto court. I wasn’t commentating now. I was coaching. Sending good heart and advice through the ether to SW19. Just making sure he got the memo, making sure he understood how to play.

In prison, there’s a way you communicate when you want to celebrate. You can’t text people, you can’t organise a party. So you bang on the wall. You bang on the door. You bang things together – cups and cutlery, chairs and beds.

On my first night in prison and over those first few weeks, it had been the screaming and the distress that filled my ears. Now the noise was just as intense, but for a different purpose.

When Novak won the second set, all I could hear throughout my wing was that banging. Ike and Shuggy next door, Alex opposite. All the others down the corridor on the ground floor, Baby Hulk and his mates on the next floor up.

They were all watching. They were all with Novak. They were all with me. And when Novak won, and raised his arms, I stood up and I raised my arms, too. And as I did so, the noise along the wing broke out again, louder than ever before.

The banging didn’t stop for ten minutes. It had taken me two weeks to educate them that this was my man, and now I realised. They had understood.

I stood there and I cried. Everything coming out – the tension, the doubts, the stress, the hope. The love I felt for Lilian and my children, the love I felt for Novak. For Centre Court, like a portal that July afternoon, bringing us all together.

Then Ike and Shuggy were standing in my doorway. ‘Wow, Boris, your man won, he won…’

I thought about all the things I had learned about Stoicism, when night came and my door was locked again and all was quiet. Wimbledon is for Stoics. Train your mind and you will win. Play until the end. Don’t give up in the third set, don’t give up in the fourth. Fight until it’s over.

These brief moments sustain you in the days and weeks afterwards. They carry you through the darkness you know is coming and all the stuff you don’t.

That Sunday night I was still locked up in a tiny cell 100 miles from those I loved. My life was inside. But in my mind I was flying.

© Boris Becker 2025

Adapted from Inside by Boris Becker, to be published by HarperCollins on September 25, priced £22. To order a copy for £19.80 (Offer valid to September 27; UK p&p free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.