This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

It’s blockbuster season, with race cars, zombies and superheroes fighting for control of cinemas whose chief appeal may be that they have air conditioning. First up: F1, with Brad Pitt as — stop me if you’ve heard this one before — an aging racing driver tempted back for one last job.

It’s written by Ehren Kruger and directed by Joseph Kosinski, who last worked together on Top Gun: Maverick, which starred Tom Cruise as an ageing fighter pilot tempted back for one last job. The similarities don’t end there.

Both see an actor who was huge at the end of the last century mentoring a bunch of younger actors whose names you struggle to remember. Both feature sequences involving powerful machines moving very fast, made possible by small high-definition cameras, that are breathtaking. Both feature beautiful people acting whilst wearing huge helmets.

And both feature antagonists who are vague and absent. With Maverick, the decision not to say which nuclear-curious country the US was bombing (let’s face it, probably Iran) felt like a market-maximising political decision. With F1, you feel there’s a more nakedly commercial force at work.

To watch this film is to feel the weight of its sheer effort to sell its product. More than Barbie or The Lego Movie or Transformers, this is a film that wants you to understand that Formula 1 is the summit of human achievement. See the fly-bys, the glamorous locations, the beautiful cars.

There’s less emphasis on the beautiful women than there would have been 30 years ago because the Formula 1 product is a wholesome one that the whole family can enjoy. Even when Pitt goes to bed with someone, it’s incredibly chaste. Maverick had that quality too, but it seemed a function of Cruise’s increasing distance from the rest of humanity. With Pitt, who still oozes raw sexuality, it just feels strange.

The film is enjoyable in an utterly predictable way, but you feel the filmmakers negotiating a tricky series of turns laid out for them by the product they’re trying to sell.

Apple apparently has a rule that characters aren’t allowed to use iPhones if they’re villains. In the same way F1 is constrained in how people associated with the Formula One product can be portrayed.

No one here is mean or incompetent. There are no bullies. The drivers love their mothers. The racing is exciting but not too dangerous: a horrific crash just puts a driver out for a couple of races. When an antagonist eventually has to appear, it’s made clear to us that they were someone who never really understood the Formula 1 product. No real fan of the Formula 1 product could ever be an antagonist.

Lewis Hamilton is listed as a producer at the start, creating possibly the biggest cliffhanger in the film: how will he be allowed to lose a race in a way that doesn’t imply that he’s an inferior driver?

And we haven’t even got to the product placement. The cars and the drivers are plastered with logos but so is the screenplay, with sponsors namechecked constantly. In one shot of a driver’s kitchen there are two Ninja products, their logos turned towards the camera. I began to feel as though I had overdosed on capitalism.

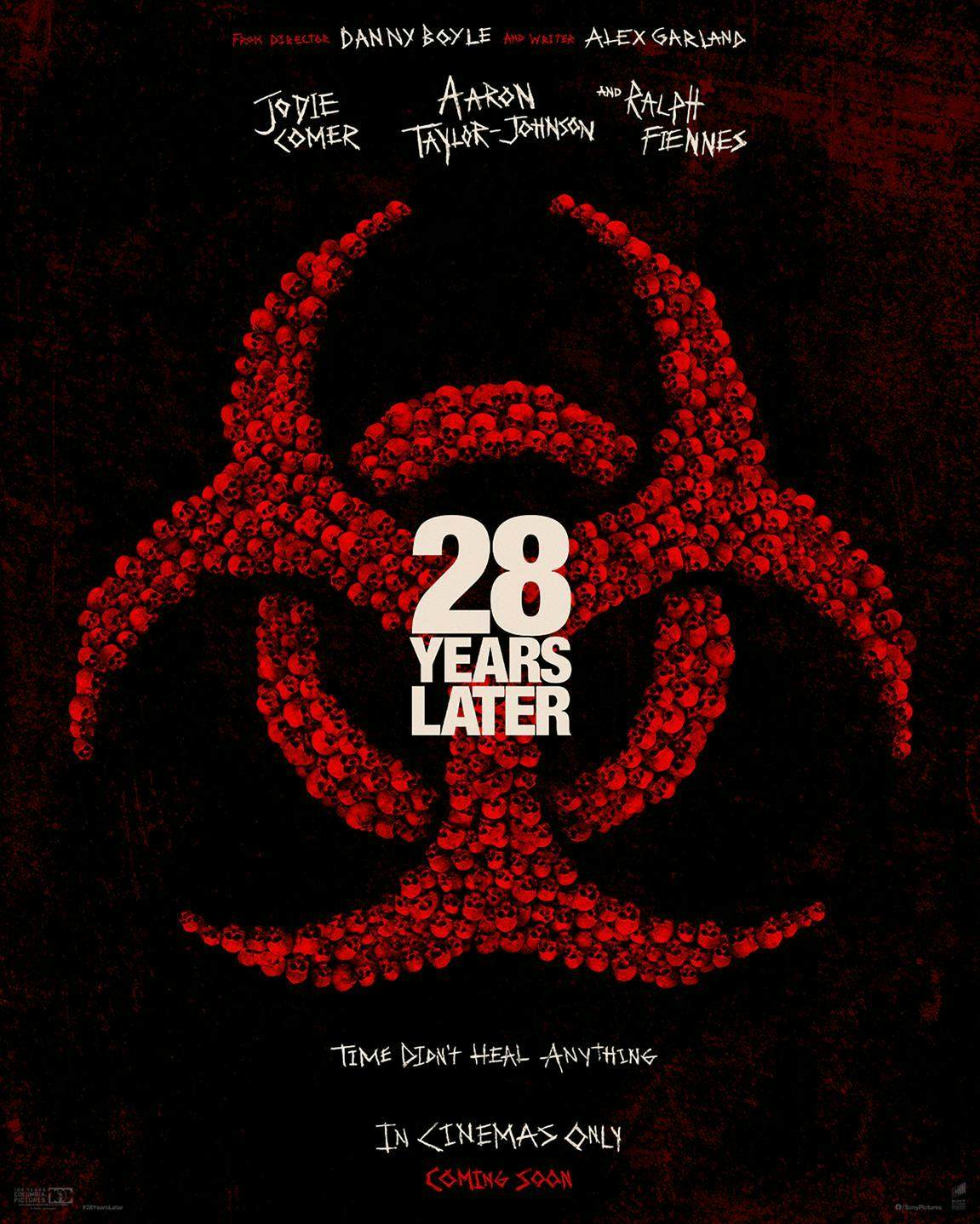

As a cure, I turned to 28 Years Later, where the two societies on offer are commune and zombie. Back in 2002, 28 Days Later helped kick off a run of high-end zombie tales. My appetite for horror is small, but this was a clever British film with something fresh to say. Writer Alex Garland and director Danny Boyle have reunited for a film set in the same world.

A generation after the previous film, Britain has been quarantined from the rest of Europe. Sadly, it is unable to make full use of the Brexit freedoms because more or less the entire population is infected by a virus that fills them with rage and makes them want to eat human flesh.

Only the island of Lindisfarne remains safe, protected by the sea and a watchful population. Jamie, played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson, is a scavenger, licensed to visit the mainland in search of supplies, who’s decided it’s time to take his 12-year-old son Spike, played very well by Alfie Williams, with him. This is a superior horror that thinks about the world it is creating. It was, by the end, quite moving. A sequel will be out next year.

It’s the kind of film that, 40 years ago, would have appeared late on a Sunday evening, after a quirky introduction from a gaunt man with his T-shirt tucked into his jeans. The British Film Institute is in the midst of a season celebrating BBC2’s Moviedrome strand.

It’s hard to remember now what life was like when the films you could see were essentially chosen for you by channel controllers and the proprietor of your local video rental shop. Moviedrome, launched in 1988 and initially fronted by director Alex Cox, gave us films that were different or interesting. They weren’t all obscure: I saw An American Werewolf in London and The Terminator here. But for many of us, it revealed a world beyond Blockbuster.