This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

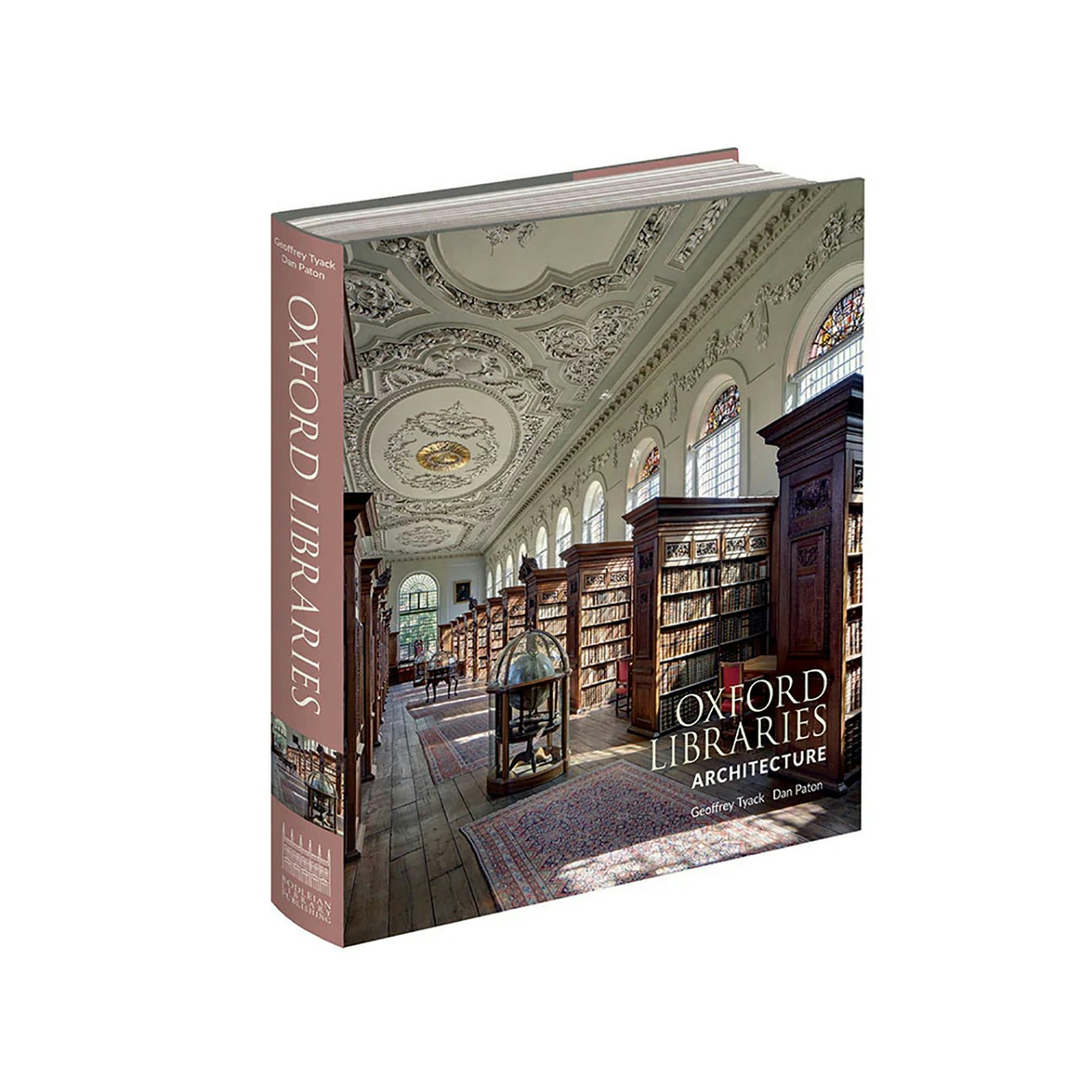

It has become an almost unavoidable journalistic cliché that an article on Oxford should open by quoting Matthew Arnold’s famous evocation of a “city of dreaming spires”. But, as Richard Ovenden points out in the preface to Geoffrey Tyack and Dan Paton’s magnificent book on the University’s libraries, it could perhaps be better described as a “city of books, which at times seems almost to have been built of books”.

Books, and the libraries that house them, are at the heart of the University’s identity. Its heraldic emblem is a book adorned with the motto dominvs illvminatio mea, “The Lord is my light.” Indeed, perhaps the most distinctive of all the landmarks on the cityscape so admired by Arnold is not a church spire but the dome of a library, the Radcliffe Camera, designed by James Gibbs to honour a legacy left by Queen Anne’s one-time physician, Dr John Radcliffe.

Surrounded by the spiky pinnacles and crockets of the medieval buildings it neighbours, the brooding hemispherical mass of what Sir John Betjeman termed “the Radcliffe’s mothering dome” marks the intellectual and physical heart of the University: Radcliffe Square, adjacent to which stands the historic core of the Bodleian Library.

The Bodleian is the most famous of Oxford’s libraries, but it is far from being the sole subject of this book. Indeed, the Bodleian is actually a collection of 26 different library spaces. Nor are these the only libraries available to scholars at Oxford. Every one of the University’s 39 constituent colleges has its own library, added to which is the Bodleian’s formidable and increasingly popular online offering, Digital Bodleian.

It is a reflection of the astonishing diversity of Oxford’s libraries that the 46 examples (one at Oxford Brookes) described and illustrated in this book only constitute a fraction of the total number of library spaces that are today available to students and scholars.

The story of Oxford’s libraries is in many ways the story of the University itself. At first, libraries were spaces that were reserved for the use of the University’s fellows. This only changed in the 19th century, when the expansion of the University curriculum heralded the arrival of the first College libraries built with students in mind.

The arrival of women’s colleges brought further wide-ranging changes: with female members of the University unable to borrow books from its central libraries, these colleges had to make provisions of their own. As a result, in 1902–03, Somerville College built the first library intended for use by both fellows and students to designs by Basil Champneys.

Changing technologies have shaped the development of library spaces as much as the requirements of their readers. When in the Middle Ages books — which were then painstakingly produced by monks writing on vellum pages — first graduated from storage in heavy wooden chests to stand upright on lecterns, they were so costly they had to be chained to them for safe-keeping. As a result, medieval manuscripts had to be stored with their pages and not their spines facing outward; readers could only consult them in situ, sitting at specially designed wooden stalls.

Purpose-built libraries were expensive undertakings and often had to be retrofitted to keep up with technological changes.

Perhaps the greatest of these shifts — until the advent of the digital age — was the invention of the printing press, which caused books to be produced in numbers far beyond that which was possible in medieval scriptoria. In Oxford, this meant that librarians had to rethink the way in which they stored books. The result was a now ubiquitous item of furniture, the bookcase, of which perhaps the first ever examples were installed in Merton College library in 1588–90. Oxford, however, is a place that is famously resistant to change; the books were not liberated from their chains at Merton until 1792.

Storage is a perennial concern. As collections have grown inexorably through bequests, legacies (some now controversial, such as those which built the now-renamed Sackler and Codrington Libraries) and acquisitions, library spaces have needed to grow. When the Radcliffe Camera first opened in 1747, there were books only around the edge of the first floor; today, the ground floor and two excavated basement levels are packed with them.

Over eight centuries of library design are covered in these pages, which have produced some of the most beautiful reading rooms anywhere in the world. It is hard not simply to gawp, for instance, at Paton’s photographs of the Old Bodleian, of which Duke Humfrey’s Library, the great gift of Henry V’s younger brother, forms the core.

Duke Humfrey’s can now be visited on pre-booked tours, but many college libraries are closed to visitors, including members of other colleges, so the book allows even dons to make armchair visits to the Baroque majesty of the library at Lincoln College (formerly Henry Aldrich’s All Saints’ Church), the polychrome Gothic splendour of Champneys’s aisled library at Mansfield College or the clean modern lines of Arne Jacobsen’s library at St Catherine’s, which Tyack deems “revolutionary, at least by Oxford standards”.

More recent commissions show that colleges are still capable of commissioning libraries that are both functional and aesthetically beguiling spaces, as is shown by recent examples at St John’s and Magdalen (both by Wright and Wright). Readers might spend less time lingering on some of the University’s recent non-collegiate commissions, however: few could love the austere, computer-oriented library at the Saïd Business School by Jeremy Dixon and Edward Jones (“a tricky brief”, as Tyack tactfully notes).

Even in the age of digital access, books still need physical homes. No image better illustrates this than Paton’s photograph of the Bodleian’s storage facility at Swindon, which houses ten million books, stacked on a seemingly endless array of metal shelving units.

The functional, strip-lit facility is not unlike an Amazon warehouse, but it is arguably far more representative of the cutting edge of library technology than the bold forms and chrome-plated exterior of Zaha Hadid’s library for the Middle East Centre at St Anthony’s College, a building Tyack reasonably suggests is “equivalent perhaps to William Butterfield’s Keble in its ability both to shock and to fascinate contemporaries”.

Books are fetched from the Swindon facility and delivered to Bodleian readers within hours thanks to a system of barcodes and online order forms that shows how technology has opened up new possibilities.

There can be few authors better placed to write this book than Tyack. An architectural historian who has spent almost his entire career in Oxford, Tyack is today the leading authority on the city’s architecture. Always wearing his prodigious learning lightly, he approaches these libraries as an historian rather than a critic, expertly guiding the reader through stories that are far more complicated than he makes them seem.

However, this is a book of both words and images, and Tyack’s lucid prose finds a match in Paton’s magnificent photography. Artfully composed so as to show the stained oak shelves of older examples and the white-washed walls of the modern to their best advantage, Paton’s photographs bring vividly to life spaces that are in many cases completely inaccessible to tourists.

Gorgeously produced by the Bodleian’s own imprint, this celebration of some of the country’s most beautiful repositories of learning will, as another cliché goes, make a handsome addition to any library shelf.