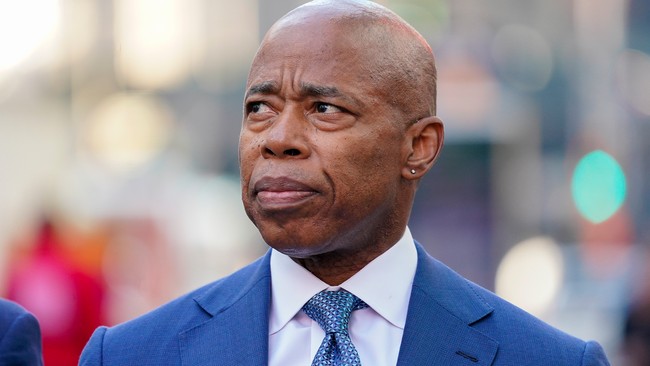

Book of the Month is The Woman Who Laughed (Riverrun/Quercus, 2025, £12), the latest of Simon Mason’s “Finder Mysteries”. There is humour, with coleslaw spilt in “a moment of excitement” in a massage parlour’s jacuzzi — “should be accepted by the business as a normal occupation risk. He’d always found food erotic and coleslaw in particular”, and with Puck, the direct student compared to Anne Elliot in Persuasion who is a motif in the novel:

What her father had done was to demonstrate once again the failures of patriarchy, she said, but she would refuse the opportunity he’d given her to theorise, she wouldn’t allow him to find refuge in the general male failure, for he was a particular and specific arsehole.

However, the major theme is grim, as is the setting, much in a dystopian Sheffield. Ella Bailey disappears in an alley there in 2020, one of three murdered Black sex workers, and there is the conviction of Michael Godley for all three. He confesses. Yet, her body is not found, and in 2025 there is the report of a sighting of Ella soon after another sex worker is murdered. The Finder is called in by the police and untangles the histories and worlds of Ella in a brilliant tale, at once searching, believable, short, well-written, and provided with a Maigret-like protagonist who is used by Mason to offer a wise humanity in another brilliant novel.

There is much competition for that position this month. The second Sally Smith comes very close. After her excellent A Case of Mice and Men, we have A Case of Life and Limb (Raven, 2025, £16.99), set in 1901, in which Sir Gabriel Ward has to deal with the arrival in parcels to distinguished colleagues of the Inner Temple of parts of a mummified body, and also with representing Topsy Tillotson, a music hall star, in her libel action against the Nation’s Voice, a scandal sheet. We have the top-hatted world of the Temple, malice and vicious competition alongside Gabriel’s calm scholarship, the well-observed dynamics of class and gender conventions within and outside the Temple, police procedure, muckraking journalism, fine courtroom description, murders, tombs and homosexuality, all delivered with calm, skill, wit, humanity and a searching reaching into personalities and values. There is a wonderful sense of time, as in:

‘Do you know of digestive biscuits, Sir? … ‘made specially by McVities to a secret recipe … If only someone would sell them covered in chocolate.’

‘No doubt someone will, one day’

and we smile with Gabriel. A great story.

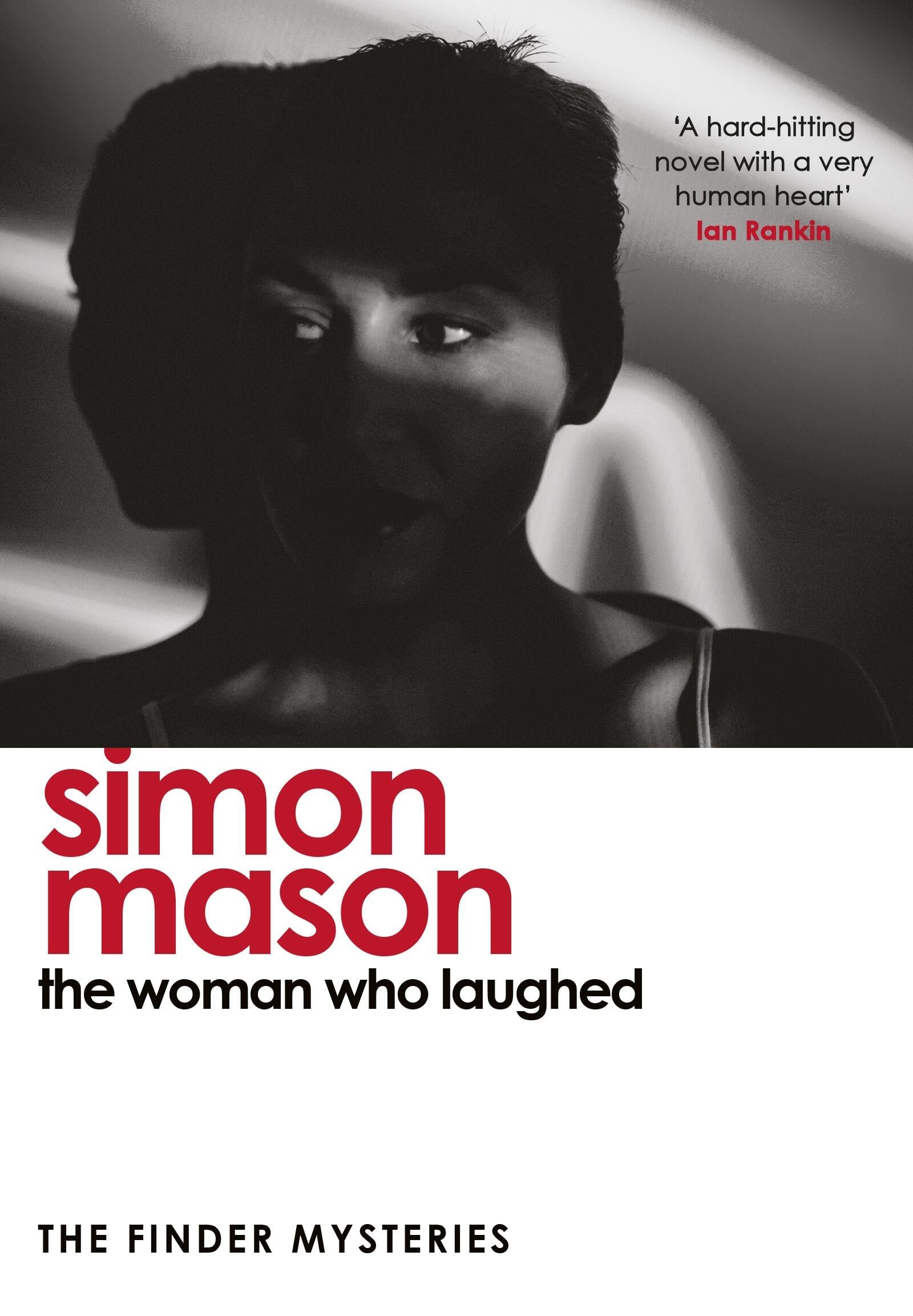

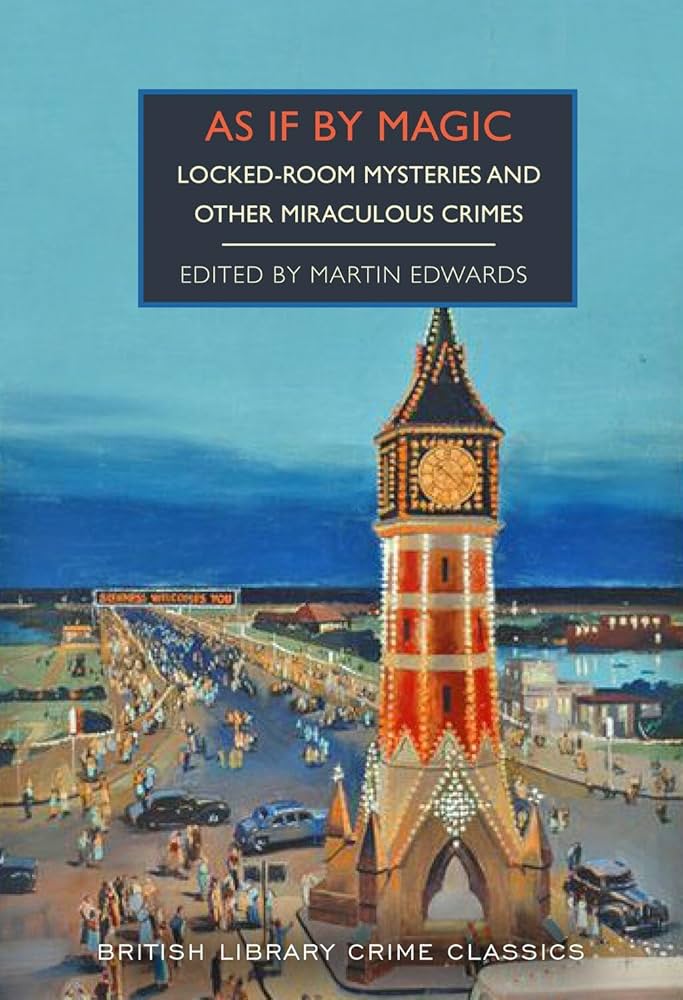

The other very near-run is Martin Edwards’s As If By Magic. Locked Room Mysteries and Other Miraculous Crimes (British Library, 2025, £10.99). This is more chunky and more coherent than many of his other collections, with 16 impressive pieces. Bookended with two by John Dickson Carr, the volume offers both well-known authors and those who are less prominent. Begin with the very fun “The Last Meeting of the Butlers Club” by Geoffrey Bush, a witty and well-informed 1980 satire on the norms, mores and social emphasis of the Golden Age, with a rewriting of some famous characters, notably Dr. Thorndyke. Carr’s “The Wrong Problem”, his first short story to feature Gideon Fell, is a brilliant and sinister one, with a disturbed murderer, and family dynamics that capture a standard conceit of the period. L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace do it with magnets in a differently haunting story that has echoes of Poe. F.C. Bentley’s “The Ordinary Hairpins” brings in Philip Trent to investigate a disappearance, Will Scott’s “The Vanishing House” has the vagrant Giglamps solve an impossible murder, and Margery Allingham does the same with Campion in “The Border-Line Case”. Vincent Cornier possibly is overly keen on his science in “The Shot That Waited”, but science is a possible cause of murder in Grenville Robbins’ “The Broadcast Body”. Anthony Wynne’s “The Gold of Tso-Fu” is somewhat mannered and a trifle predictable, Hal Pink’s “The Two Flaws” and Ernest Dudley’s “The Case of the Man Who Was Too Clever” again deal with matrimonial troubles, James Ronald’s “Too Many Motives” is mannered and weak, Christianna Brand’s “Murder Game” is brilliant on insanity and uses the standard theme of bad blood, while Michael Gilbert’s “The Coulman Handicap” is somewhat slight. Julian Symons’ “As if by Magic” is short but effective, and Carter Dickson’s “The House in Goblin Wood”, Carr’s only short story to feature Henry Merrivale, very impressive.

With reference to Brand, it is well worth seeing Green for Danger, the 1946 film of her 1944 novel, with Alastair Sim as a different Inspector Cockrill and the setting during the VI raids rather than the Blitz. With Wilkie Cooper’s cinematography, this is a film of gripping images, not least the figure who confronts Sister Bates. Sim is shown reading a detective novel and picking the wrong culprit.

George Orwell’s “The Decline of the English Murder” (1946) was a short postwar essay more memorable for its title than its perception. A journalistic piece, published in Tribune on 15 February, the clarity of the argument rested on a counterpointing of a classic period of murder, that of c.1850-c.1925 with “the old domestic poisoning dramas” the “product of a stable society where the all-prevailing hypocrisy did at least ensure that crimes as serious as murder should have strong emotions behind them” with a subsequent age characterised by the impact of Americanisation, a process taken further by the impact of World War Two. He focuses on the Cleft Chin murder of 1944 in which an American deserter was the killer, while the British victim, George Heath, had been wounded at Dunkirk in 1940. Orwell concluded with a reflection both on the culture of the war and with a comment on the resonance of murder:

” … the whole meaningless story, with its atmosphere of dance-halls, movie-palaces, cheap perfume, false names and stolen cars, belongs essentially to a war period … it is difficult to believe that this case will be so long remembered as the old domestic poisoning dramas, product of a stable society where the all-prevailing hypocrisy did at least ensure that crimes as serious as murder should have strong emotions behind them”.

There was a clear relationship with the norms established and sustained and reflected in novels and the press. Earlier in his piece, Orwell had referred not only to the News of the World but also to “successful novels based on” true-life murders and on “episodes that no novelist would dare to make up”. There is of course a caricature of the interwar Golden Age detective novels that suggest a stability that was to be replaced by a more disturbing, violent, and psychologically engaged crime fiction. Orwell in part contributes to this distinction, but, possibly, some additional points should be made, and notably so in terms of the fiction of the period.

To a degree, there was support for Orwell in Christie’s novels. In Crooked House (1949) there is the looking back with “in the name of respectability had been committed” and, instead, reference to a more disturbed present, with the crisis of country-house living in Mrs McGinty’s Dead (1952), as in Francis Duncan’s Murder for Christmas (1949) and Henry Wade’s Too Soon to Die (1953), and, in the first, Poirot reflecting “He recalled vaguely a small paragraph in the papers. It had not been an interesting murder. Some wretched old woman knocked on the head for a few pounds. All part of the senseless crude brutality of these days”. In her deeply pessimistic Hallowe’en Party (1969), there is reference to “sordid and uninteresting crimes”.

In part, however, there is the standard problem of simplifying a previous age for there were crimes such as the Cleft Chin Murder in the interwar period and, indeed, prior to World War One. Orwell’s piece about the disruptive nature of change could also have been made about large-scale industrialisation, internal migration and secularisation in the nineteenth century, about the social tensions of the Edwardian age, about World War One, about the “Roaring Twenties” and about the Depression. Change was very much captured in the fact and fiction of the late nineteenth century, not least the pretended identities found with much migration and indeed in the Sherlock Holmes stories, as well as in the Cleft Chin Murder, where the murderer claimed to be an officer.

Orwell perforce simplified the changes in the response to crime. A major one, captured by Christie in her early stories, was the adoption of the psychiatric approach linked to Sigmund Freud. Indeed, Poirot argued that he did not need to attend the scene of a crime in order to understand it, and, in this, Christie very much contrasted her creation with that of Conan Doyle, who was still writing Sherlock Holmes stories in this period. That was not a perspective that meant much to Orwell, no more than did the marked development in police doctrine and methods that was linked to, but not restricted to, the reforms of Lord Trenchard, the Metropolitan Commissioner of Police from 1931 to 1935, under whom the Metropolitan Police College was opened at Hendon in 1934. These reforms were continued by his successor until 1945, Air Vice-Marshal Sir Philip Game for whom political stability and wartime measures were crucial, rather than murders.

Orwell should not be criticised for offering far less than a full account of developments, but his counterpointing was descriptive rather than analytical, and there was a misleading account to the description.

Tom Mead has already achieved a high reputation as a modern practitioner of the classic Golden Age novel, with a particular skill at locked-room mysteries that are resolved by Joseph Spector, his illusionist who has become a solver of mysteries. Aside from introducing me to the word caliginous, his new novel, The House at Devil’s Neck (Head of Zeus, 2025, £20), is a deliciously clever work, as good as the most demanding John Dickson Carr, and with an atmosphere of creeping evil. Devil’s Neck, a frightening mansion on an island only reached by causeway, is an old World War One hospital, visited in 1939 by a group seeking spiritualist entrées, “quite a mismatched crowd to be spending a weekend in a haunted house”. Proprieties are breached — “A séance … before dinner?” — and the quest for the occult is a source of a humour that becomes horrific. Many echoes from World War One in a tale of multiple murders, concealed identities, and a formidable pace of deduction, all ably written and with fine characterisation. Deserves much praise.

Another excellent addition comes from Pushkin Press’s already strong list in Japanese detective fiction, not least the stories of Seishi Yokomizo (1902-81). Murder at the Black Cat Café (2025, £10.99) has a misleading title as you get two stories, first published in Japanese in 1975, that and also “Why Did the Well Wheel Creak?”. They each star his wise private detective Kosuke Kindaichi and deal with issues of identity and identification. Set in 1947 and 1946 respectively, these stories are highly instructive on the aftermath of the war and the return of Japanese from China, and also address issues of status, wealth, and personal and family position in a traditional society struggling with change. But, more to the point, they are excellent stories with much puzzlement.

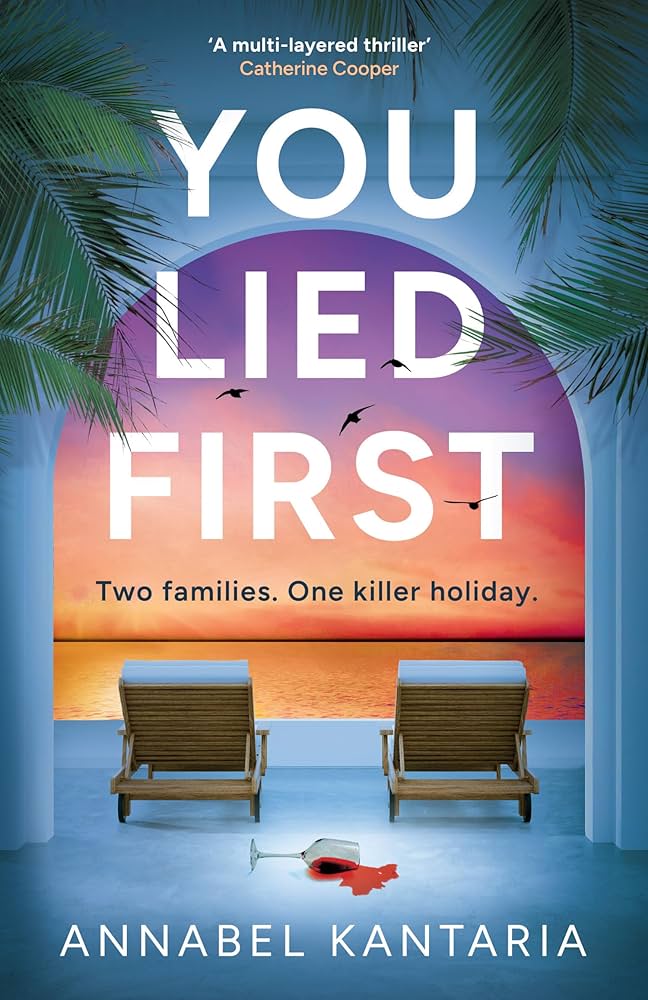

So also with the very different You Lied First (HQ, 2025, £9.99) by Annabel Kantaria. Set in Oman and Britain, the latter dank and depressing, the former apparently a perfect opportunity for a week’s holiday in the sun. Kantaria is brilliant in her slow-burn revelations of the tensions that grow up among the British abroad, with sex, class and, in particular, personality making a family holiday together the cause of murder. The characterisation is excellent, the plot works well, as does the resolve, and this is a very good easy read.

The ever-skilful Janice Hallett strikes home again with The Killer Question (2025, Viper, £18.99). Set near where I grew up (now that’s a matter of opinion), this centres on “The Case is Altered”, a country pub where the landlords, Sue and Mal Eastwood, seek distinctiveness and profit by organising pub quizzes. I have only done one of these: it was an unexpected accompaniment to a meal in a pub and it was interesting albeit slow. At least there was not the menace and eventual mayhem of Hallett’s well-realised cast. The quizzes face the challenge of cheats, and the pub, first, the discovery of a body nearby and then the disappearance of Sue and Mal. Hallett proceeds by means of her usual pot pourri of sources, in this case including exchanges between neighbouring pub landlords, a variety of police sources, and a mass of emails, text and WhatsApp messages. Lots of clues, such as reference to Jacobean Revenge plays, but the clues are themselves puzzles and neither plot nor resolution can be described as linear. That contributes to the fun which is there from the start, as with the one-star food review complaining about a stone cold starter covered in a layer of tough yellow horse fat, in fact huîtres en pot salad with seasoned butter. A book to appreciate and enjoy: so much more than the plot.

Hallett’s method, of multiple sources, is in part used by Martin Edwards in his excellent Miss Winter in the Library with a Knife (Head of Zeus, 2025, £16.99), a work that also draws on the conventions of closed-cast Golden Age stories and that has a cluefinder at the close. Placed in a snowy North Yorkshire, the fictional Midwinter Trust has set a game around the murder of a fictional crime writer, only, in the conventional fashion, for a murderer to intervene. First-rate, and lots of humour at the expense of the personnel and mores of the modern world of books.

Sherlock Holmes has not generally brought forward good imitators or spin-offs. In particular, as with Horowitz’s attempts, there is a tendency to overlong offerings that do not provide Conan Doyle’s crispness. In contrast, A Detective’s Life. Sherlock Holmes, edited by Martin Rosenstock (Titan Books, 2022, £8.99) provides a Prologue and then twelve contributions that follow Holmes through his life, ending in a re-run of the Reichenbach Falls. This is an excellent collection, satisfying, varied, and tone-alive to the skill and qualities of the originals.

Penguin continues with its excellent edition of Elmore Leonard’s work as part of the “Crime and Espionage” list in Penguin Modern Classics. Recent arrivals include 52 Pickup, City Primeval and Cat Chaser (all 2025; £9.99), all previously published, some in Britain by Viking and in America by Arbor House, and Picket Line and Other Stories (2025, £8.99), the last three stories, the first, and by far the longest, “Picket Line”, having hitherto been unpublished, while “Chick Killer” and “Ice Man” had only appeared in periodicals. “Chick Killer” deals with a violent arrest of a chick killer, while the other two address racism and the oppression of minorities. Authority figures emerge as vicious and as vindictive users of the law. “Picket Line” is meditative, a fine piece of observation and writing, and ends with a consideration of different forms of resistance.

City Primeval has Elmore’s customary drive, and also a play of personality in the rivalry between the unrestrained killer, Clement Mansell, and the more complex detective Raymond Cruz, who can also be a killer. There is a corrupt judge, two very different female central characters, the well-observed racial tensions of Detroit, and a plot of urgency and power, with the two protagonists throughout well-matched. The relationship between a flawed law and a difficult justice is central, as in so many American police thrillers.

52 Pickup, originally published in 1974, has an affair by Harry Mitchell lead to blackmail and murder in a story that does not involve the police. The seediness of crime and the purpose of revenge are both central.

If you appreciate the novels of Philip Kerr, Simon Scarrow and Robert Harris, then Rory Clement’s Evil in High Places (Penguin Viking, 2025, 2025, £16.99), set in Munich in 1936, is probably going to be a disappointment. His re-creation of the Third Reich is not as searching. But there is a more serious problem. The “heartfelt thanks” to a diligent and brilliant editor who has helped to make the novel what “I always wanted it to be” raises the question of what it might otherwise have been. Unfortunately, there is far too much poor writing while much of the dialogue is unconvincing, lame, filling the space, and written by numbers as in ” … with the weather closing in and the temperature dropping, it was not so pleasant. As he neared the mountains, the roads became icy and he was worried about the state of his tyres. Even at this time of year, however, the Bavarian countryside would always look beautiful to Seb … The castle guarded the area like a sentinel … he sensed a warmth and honesty to Elena Lang. He would have liked to know her better … ” There are so many mediocre novels that are better written. This is one to miss.

Instead, focusing on DCI Frank Merlin in London, the novels of Mark Ellis offer a more interesting and accomplished portrayal. Stalin’s Gold (2018) was republished in 2020 as In the Shadows of the Blitz. The 2023 paperback (Headline Accent, £12.99) is a satisfying read, set from 1 to 18 September 1940, and, although Stalin, Hitler and Churchill all make brief appearances the story is very much located in a London under bombings, with the fate of some of the gold shipped from Republican Spain to Stalin a matter of an acute competition that involves conspiracies and killings. Alongside the Soviet state and the Polish Government-in-Exile, there are entrepreneurs and would-be free agents in plenty, from bankers to looters, killers to aristocrats. Anthony Blunt turns up, but most of the characters are fictional. The details of aerial dogfights are handled well as are the arbitrary consequences of the bombing. Impressive.

I personally find reunion accounts of return-to-crime scenes somewhat overplayed as plot devices, but, for those who like them, there is Zoë Rankin’s New Zealand-set debut The Vanishing Place (Viper, 2025, £9.99), and Bronwyn Rivers’ Australian debut, The Reunion (Constable, 2025, £9.99).

Adele Parks’ Our Beautiful Mess (HQ, 2025, £16.99) is a family drama with violence, one I found overlong and not written with any distinction.