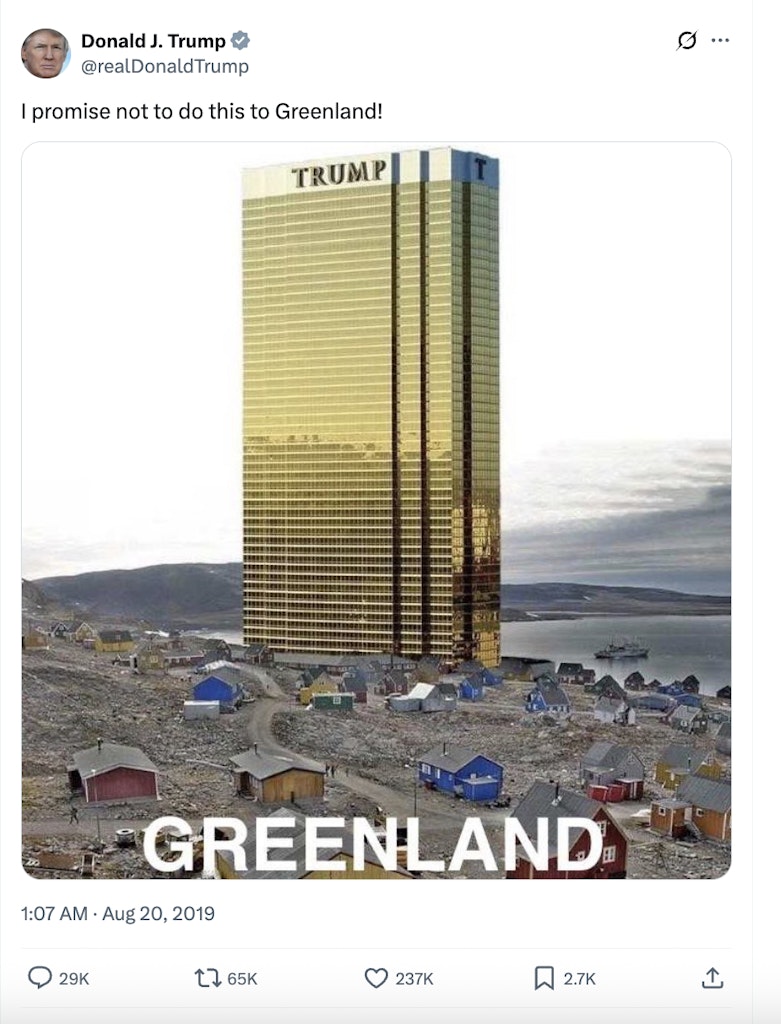

Not so isolationist, then? Seven months into the second presidency of Donald Trump, the word “isolationist” is a demonstrably inaccurate description of this ruler’s statecraft. If bombing Iran and calling for “regime change” in Tehran, or embroilment in Gaza, or brokering talks with Kyiv and Moscow (or Delhi and Islamabad) and making covetous claims on territory from Canada to Greenland to Panama count as isolationism, the term is vapid.

Indeed, half a year into the wind, it is the faction of the MAGA base most opposed to entanglement abroad that has the most complaining to do. Ah, but what about the tariffs and the economic walls Trump erects? Trump’s aggressive industrial protectionism also earns the charge of isolationism. But then, cold warrior President Ronald Reagan imposed punitive tariffs too, including on allies. Economic coercion does not preclude ambition beyond the water’s edge. It’s the kind of factoid you don’t get instantly from Wikipedia. Slogans might be the problem to begin with.

Yet the old, loaded word is also relentless. It survives, thanks to a convergence of politics and the state of the commentariat. First, politics: it is convenient for advocates of American primacy in the world to recast all dissenting views as parochial, backward and primitive, defects all captured in the term “isolationism.” Framing the essential foreign policy choice as a binary one, between “global leadership” (nice euphemism) and a withdrawal to Fortress America is a rhetorical ploy, reinforced by historian Stephen Ambrose” harmful but influential postwar text. Its grip on those seeking respectability in the world of polite society is still tight. In the graduate lounge, the power lunch or the international security summit, support for a commitment to dominance in all key theatres is a high status opinion, support for reducing the footprint a low status one.

And because “isolationist” is both pejorative and vacuous, enthusiasts for ever-expanding commitments can use it to taint any proposal for limitation, from Trump’s withdrawal of a limited commitment to the Kurds to President Joe Biden (and Trump’s) restrictions on the use of American missiles against Russia. The argument over particular localised strategies (garrisons or targets) occludes the larger, grand-strategic reality that the US is heavily embroiled in the Middle East and has helped donate the largest weapons aid package in history to Ukraine.

And then there is the state of the commentariat. There isn’t a polite way to say this. Where serious thinking is scarce, slogans abound. In truth, describing and explaining a state’s outward behaviour and its impulses is harder than it looks. The true divide in US foreign policy today is not between enlightened believers in world hegemony and knuckle-dragging provincials. It is a three-way struggle — and conversation — between primacists (those who favour a forward-leaning preponderance of power via commitments in north-east Asia, the Middle East and Europe, with all the optimism implied), prioritisers (those who believe Washington should rank and rebalancing its commitments in line with its strained power) and restrainers (those who strongly presume against militarised engagement, but who often prefer other types of active internationalism, via peace-making institutions, grand bargains over climate and the general pursuit of more egalitarian solidarity between peoples).

Foreign policy discussion is corrupted by easy access. It is far too easy for the well-heeled to get a degree and then acquire a media megaphone to pronounce on diplomacy, yet without doing their homework, and bringing only thin historical awareness and little reflection about the concepts they casually throw around. And a significant per centage of those commentators share the unreflective prejudices built into the internationalist-isolationist slogan. Stuck for a neat summary and writing to a deadline? Insert “isolationist.” Confronted by populations that want more to be done about pressing domestic problems, and scarce resources to be better distributed to those who pay taxes? Brand them “inward looking.” Lose a vote on the issue? Warn superficially about the rise of “angry populism.” Indeed, the glib use of the term “isolationist” is a strong predictor of those who once hurled the term “neocon” around, to pigeonhole anyone favouring military force in ways deemed undesirable.

The dismissive habit is pronounced in Europe as well as amongst the Europhile parts of the Washington national security penumbra. Trump, we hear whenever he threatens Ukraine or NATO with abandonment, is “isolationist” for doing so. For too many commentators from what used to be the world’s boss continent, Europe remains the world. In truth, the act of withdrawing from one theatre does not necessarily amount to a wholesale retreat from overseas. If threats of withdrawal somewhere make a president parochial everywhere, there goes John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter. Indeed, in its earlier existence, the Bush-Cheney faction and its associated hawkish intellectuals made a point of questioning the value of free-riding allies in Europe, before they discovered the sacred value of alliances in their opposition to Trump.

In truth, “America First” has not always been a charter for global retreat, just as its champion has always had more conflicted instincts. The slogan is more a banner than a guide to a manifesto. For what its worth, its originator was not Charles Lindbergh but President Woodrow Wilson, who ended up waging war abroad in the name of liberal internationalism while rounding up dissidents at home. Even the Fortress America anti-interventionists of the interwar period, in all their notoriety, also insisted on US dominance in Monroe territories, and prerogatives to intervene at will.

If we must have a “nutshell” summary of Trumpian America’s foreign policy, it is domination without (or with less) commitment. The US demands more, makes its patronage more conditional, it makes a point of openly coercing allies, neutrals and adversaries, while it commits to less. It consummates long-running US impatience with allies not pulling their weight (on American terms), is tired of paying the tab while getting not enough in return, not even when allies step up their efforts, and when scarce resources and the coming of determined, collaborative adversaries are focusing minds. In that sense, Trump is the coarse, demagogic and showbiz-obsessed expression of an underlying, long-term structural shift.

Significant here is the navy and the federal budget. Note Trump’s Executive Order of 9 April 2025 demanding the strengthening of shipyards: “restoring America’s maritime dominance.” This project is not just on paper. The forthcoming “big, beautiful budget” allocates 150 billion dollars to strengthening US shipbuilding, missile defence systems, munitions, drone and AI capabilities, and nuclear modernisation. It funds and prioritises Indo-Pacific Command, so it is not just intended to firm up America’s “moat.” And just recently, Trump claimed that China’s president Xi Jinping promised not to attack Taiwan while he was in office. Even pricing in the president’s vanity, this does not exactly signal apathy or detachment from Taiwan’s fate or the balance in Asia.

The inference is clear: Trump’s America intends to resist China’s bid for power. At the same time, Trump’s undersecretary for defence Elbridge Colby lays down expectations to allies Japan and Australia, that they must significantly increase their defence budgets and provide clarity about their commitments to a Taiwan conflict. Domination with less commitment.

And Trump himself? Trump the man is pulled between the urge to project power and the urge to withhold support, wielding threats of abandonment. He has long been conflicted about the Middle East, the main theatre of violence between America and its adversaries in our time. But his mix of attitudes is not just a matter of incoherence.

Resentment over the Greater Middle East helped make Donald Trump president. It was discontent with America’s wars from North Africa to Afghanistan that helped propel him to the Republican nomination in the first place. When Trump railed on stage against George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, the cocktail of messenger and message awoke something in the electorate. There had long been a constituency of Rightist, GOP-leaning Americans, in particular veteran communities, who resented the military adventures as well as the financial recklessness of the Bush-Cheney era. Only, they had not gotten their candidate. The Republican Party put up nominees every bit as committed to an expansive and militarised foreign policy. Neither Mitt Romney nor John McCain could speak to their grievances. By denouncing Operation Iraqi Freedom from the right flank, Trump appealed to conservatives who opposed the wars that maimed and alienated returning troops, and made that political orientation mainstream. Accordingly, Trump cast the region that ended up consuming earlier presidencies as a strategic backwater best abandoned, vowing to leave the “blood stained sand.”

Yet as the latest crisis over Iran has highlighted, Trump’s domestic coalition is notoriously torn on the question of America abroad, united only in the conviction that Trump’s predecessors failed. And in office, Trump’s posture towards the region was more fraught. Despite the blood and sand, Trump also grovelled before Gulf potentates. He indulged Israel’s unrelenting hyper-nationalist, Benjamin Netanyahu. This was partly a simple matter of the oligarch’s attraction to the opulence of the regimes that cultivated him. It was also a wider question of political economy. Trump was sensitive to trade imbalances, claimed to preside over an American industrial renaissance, and was resentful of nations he believed were “net recipients” in their relations with Washington. Therefore, large arms sales packages tended to placate him.

So Trump is more imperial than isolationist, but it is a particular form of imperialism, one alien to certain foreign policy traditionalists, born of both a resentment of and attraction to projecting power abroad. It is quick to coerce and constrain others’ sovereign decisions, but also quick to show anxious allies the abyss without euphemisms. But the returns on pointing this out, yet again, will be modest. None of Washington’s actual pattern of behaviour will put an end to the same old script, always to hand when observers don’t know what to say but feel they must say something.