Amid the sprawling mass of complicated statistics and medical evidence deployed by the prosecution against Lucy Letby there was one devastatingly simple piece that was viewed as little short of a smoking gun.

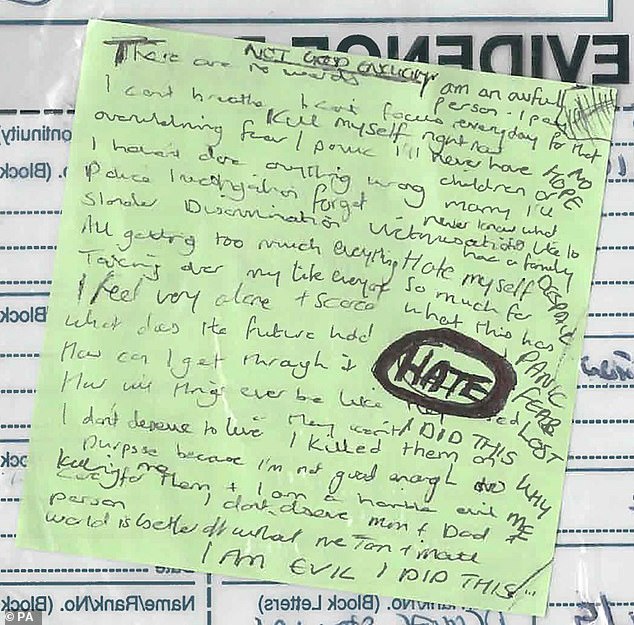

A pale green Post-it note – one of a cluster of many messy handwritten jottings found among the young nurse’s belongings at her home. On it had been written, in large, emphatic capitals, the words: ‘I AM EVIL. I DID THIS.’

However small the paper, the force it wielded was immense. How else to view this, and Letby’s other tortured laments scrawled on various scraps of paper, as anything but an admission of guilt from the worst child killer in British criminal history?

What kind of nurse, after all, would commit to paper heinous statements such as, ‘I killed them on purpose because I’m not good enough’, other than a cold-blooded perpetrator of infanticide?

That is certainly how the police and crown prosecution lawyers saw them, not to mention a great swathe of the public, for whom these damning words effectively clinched the case against Letby.

After two trials and two appeal attempts, the Lucy Letby case culminated in multiple whole life terms for the murder of seven babies and the attempted murder of seven others

Psychologist Emma Kenny sees Letby’s handwritten notes as a typical response for traumatised people who feel no one is listening to them and whose lives are unravelling

In media reports, meanwhile, her scribbles were consistently referred to as the ‘confession notes’, as if this was an undisputed fact.

Yet from the moment their existence was made public, I saw them differently.

As a psychologist for more than two decades with a special interest in criminal behaviour, my instinct was that this cache of handwritten notes was not necessarily the result of a guilty conscience, but of someone experiencing great pain – which could speak just as strongly of innocence as guilt.

Indeed, I would go so far as to say that notes such as these are a typical response for traumatised people who feel that no one is listening to them and whose lives are unravelling – especially if they have been encouraged to write down their feelings as a way of coping with extreme stress.

We now know that Letby was being told to do exactly this by her GP and the Countess of Chester Hospital’s then head of occupational health and wellbeing.

The fact this therapeutic explanation was not emphatically made plain to the jury – the defence suggested merely that they could be a symptom of anguish not guilt, and deployed no expert forensic psychologists to give evidence on how to interpret the notes – is a deeply problematic part of this ever-more troubling and complex case.

After two trials and two appeal attempts, the case culminated in multiple whole life terms for the murder of seven babies and the attempted murder of seven others between June 2015 and June 2016.

As we now know, those convictions are to be scrutinised by the Criminal Cases Review Commission. And while it is not for me to declare my belief in Letby’s guilt or innocence, I believe the prosecution’s weaponisation of those handwritten notes and the defence’s failure to offer a fully realised alternative explanation provides more than enough room for reasonable doubt about Letby’s conviction.

I write this confidently as someone who has been involved in therapeutic work for nearly 25 years, the majority of it specialising in criminal behaviour.

During this time, I have counselled thousands of troubled minds as well as provided commentary and insight for any number of TV crime series and documentaries.

And I can tell you that within the safety of the therapy room – as well as in the privacy of their bedrooms – countless people in crisis produce writing like Letby.

Not because they are truly confessing to anything, but because they are trying to pour the noise in their head on to paper in a desperate attempt to get some relief.

It’s known as stream-of-consciousness writing and is a tool deployed by therapists to help clients externalise and regulate their thoughts.

The rules are simple: write without censoring yourself, let the pen move faster than your inner critic and capture whatever surfaces, without worrying what anyone might think of them.

As a result, the words that emerge may be ugly, repetitive or contradictory – because they are not crafted for an audience, but instead are the unfiltered contents of a turbulent mind.

What they are not, in the main, is factual.

Take, by way of comparison, the journal and diary entries produced by countless young women over the years – for let us not forget that Letby (now 35) was a young woman of 28 when she was first arrested in 2018.

Many scribble horrible things about themselves as a way of externalising the complex maelstrom of emotions within.

They write things such as, ‘I’m ugly, fat and stupid’. But it’s not a fact, or even an objective truth, in the same way that writing down, ‘I want to kill myself’ (something else I have witnessed in my professional career) is not actually a statement of intent.

They are both in their own ways an expression of despair from a mind that does not know what to do with what is unfolding outside.

As for the apparent ‘remorse’ suggested by the prosecution – it could be genuine. Those tragic baby deaths happened on Letby’s watch and, as a nurse whose very job was to keep them alive, she can feel responsible for them even if she did not, as the prosecution suggested, block their airways or overdose them with insulin herself.

Indeed, this explanation was offered by Letby herself during her first trial: when asked about the notes, she said she was questioning herself and whether she had unintentionally done harm by not knowing enough or not being a good enough nurse.

Yet as we have seen, these entirely viable alternative explanations did not stop Letby’s writings becoming a key spoke in the prosecution case, which presented nearly every element of these notes as ever more damning evidence when, in fact, there are plausible explanations for all of them.

Take, for example, the ‘secrecy’ around the notes. For the prosecution, the fact they were hidden in Letby’s home was proof of her desire to conceal her guilt.

But for anyone who has worked with trauma survivors, this is an entirely predictable act. People in deep shame or fear often hide their most personal writings, not because they contain literal confessions, but because they fear they will be misunderstood.

Think again of young women’s diaries – or young men’s for that matter. By and large, the thought that anyone might read them would be mortifying at best, and devastating at worst.

They are written as a form of personal catharsis, and not designed for public view.

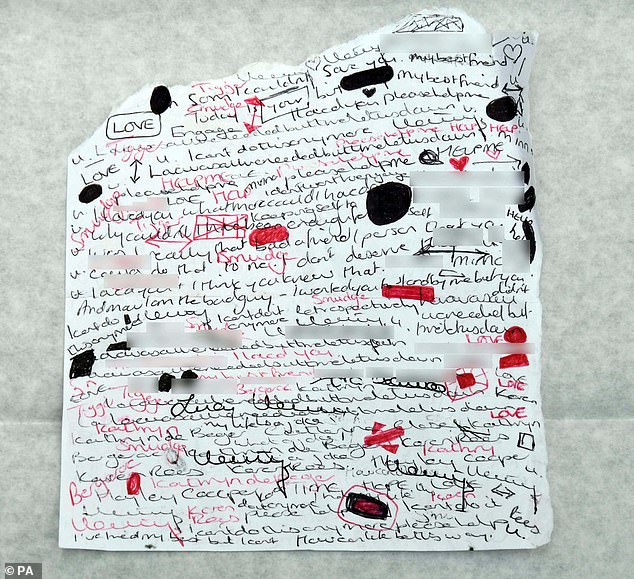

Even the structural chaos of the notes was put in the spotlight: barristers told the jury that the tangled lines, the scribbled-over names, the sudden shifts between black and red ink were signs of an agitated mind trapped in a cycle of remembering and regretting.

A pale green Post-it note – one of a cluster of many messy handwritten jottings found among the young nurse’s belongings at her home. On it had been written, in large, emphatic capitals, the words: ‘I AM EVIL. I DID THIS’

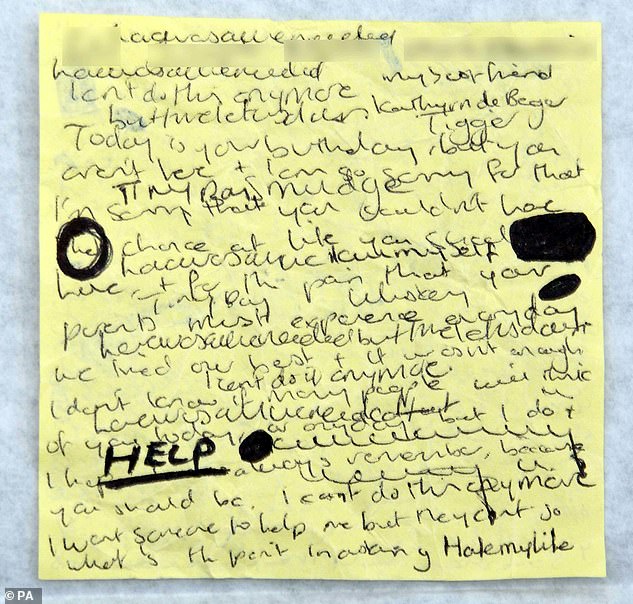

On this Post-It note, Letby repeatedly uses the word ‘help’, a cry repeated in different inks and underlined for emphasis

In another note, she wrote ‘How can life be this way?’ ‘Kill me’ was also written in bold and circled on the sheet, while other words and phrases included ‘foreign objects’, ‘despair’, ‘panic’, ‘fear’, ‘lost’

They also argued that the fact names of colleagues, parents and babies were repeated over and over was a crucial sign of a fixation: the prosecution claimed it was the mental replay of her crimes.

Again, as a therapist, I can tell you that repetition is quite usual in crisis writing. Sometimes, writing down names or events linked to trauma can be an attempt, conscious or otherwise, to process them.

At other times, it is simply a manifestation of being trapped in a negative loop in which the brain becomes a stuck record, replaying the same scenes in an often futile effort to make sense of them.

This tendency to cycle repeatedly through the same events or faces is often a hallmark of both anxiety and depression, both very credible emotional states for Letby to be plunged into given what was unfolding around her.

Let us not forget that these notes were written after Letby felt the finger of suspicion pointing her way for multiple deaths in the neo-natal department in which she worked.

If she was – is – innocent, then one can hardly begin to imagine the devastation she must have felt when she realised her name was in the frame. She would have been viscerally aware that public vilification, arrest, imprisonment and isolation beckoned.

Which brings me to some of the other statements set down by Letby of which, notably, much less was made by the prosecution team.

In one she writes, ‘I can’t do this any more’, in another, ‘How can life be this way?’ ‘Kill me’ was also written in bold and circled on the sheet, while other words and phrases included ‘foreign objects’, ‘despair’, ‘panic’, ‘fear’, ‘lost’ and – repeatedly – ‘help’, a cry repeated in different inks and underlined for emphasis.

These seem less the product of a guilty conscience than a reflection of the mental landscape of someone who, guilty or innocent, feels their life is over.

Certainly, you do not have to be a psychologist to feel the palpable threads of grief running through some of these notes. ‘No hope… no children… will never have a family’, she writes in one.

In therapy we call this disenfranchised grief, meaning a kind of mourning for futures, dreams and identities that have been ripped away, but which the world refuses to acknowledge because the person is already condemned in the public eye. To my eye, it is a howl of anguish.

And what’s particularly notable about this anguish is that it is entirely inconsistent with the portrait of a narcissistic psychopath painted by the prosecution, which suggested that Letby was so Machiavellian she would murder babies to summon the attention of a doctor she fancied on shift.

Effectively, we are asked to hold two conflicting truths: that Letby could murder in cold blood, while also demonstrating the overwhelming terror and fear we see in her writings.

It does not add up.

Plenty of people with psychopathic tendencies keep journals, but regret and fear are conspicuous by their absence.

In short, remorseful, troubled psychopaths – and if Letby is guilty, then she is undoubtedly one – don’t exist.

Of course, in a courtroom, meaning is shaped to fit the narrative each side wants to tell. The prosecution portrayed Letby’s words as the veil slipping, and her true self emerging in private. The defence argued they were merely the writings of a woman broken by the weight of false accusations.

I would argue that neither of these offerings goes remotely far enough to tackle the complex psychology behind them.

Nor does it change the unsettling fact that, ultimately, nobody other than Letby herself knows whether she did or did not callously take the lives of the babies in her care.

What is certain is that these notes came from a mind in distress, whether it be from a guilty conscience or the devastation of wrongful accusation.

In another setting, in another life, these words could have been safely explored between a client and a therapist as a starting point for understanding.

For Letby, however, they proved a crucial paving stone on the path to a guilty verdict.

- Emma Kenny is a registered psychological therapist and author of the bestselling True Crime book The Serial Killer Next Door