A recent visit to Poland, where I toured the South-East one week and the Masurian Lake District in another, prompted thoughts concerning how certain important events can be commemorated in buildings, sculpture, and by other means, yet how often man-made structures fall victim to changes of boundaries, régimes, tastes, or time. As George Crabbe (1754-1832) observed in The Borough (1810), “monuments themselves memorials need”, and Decimus Magnus Ausonius (c.AD 310-95), a poet for whom I have immense affection, wrote in his Epitaphia that “Death comes even to stone monuments and the names on them”. Indeed — and the earth is littered with such ruins.

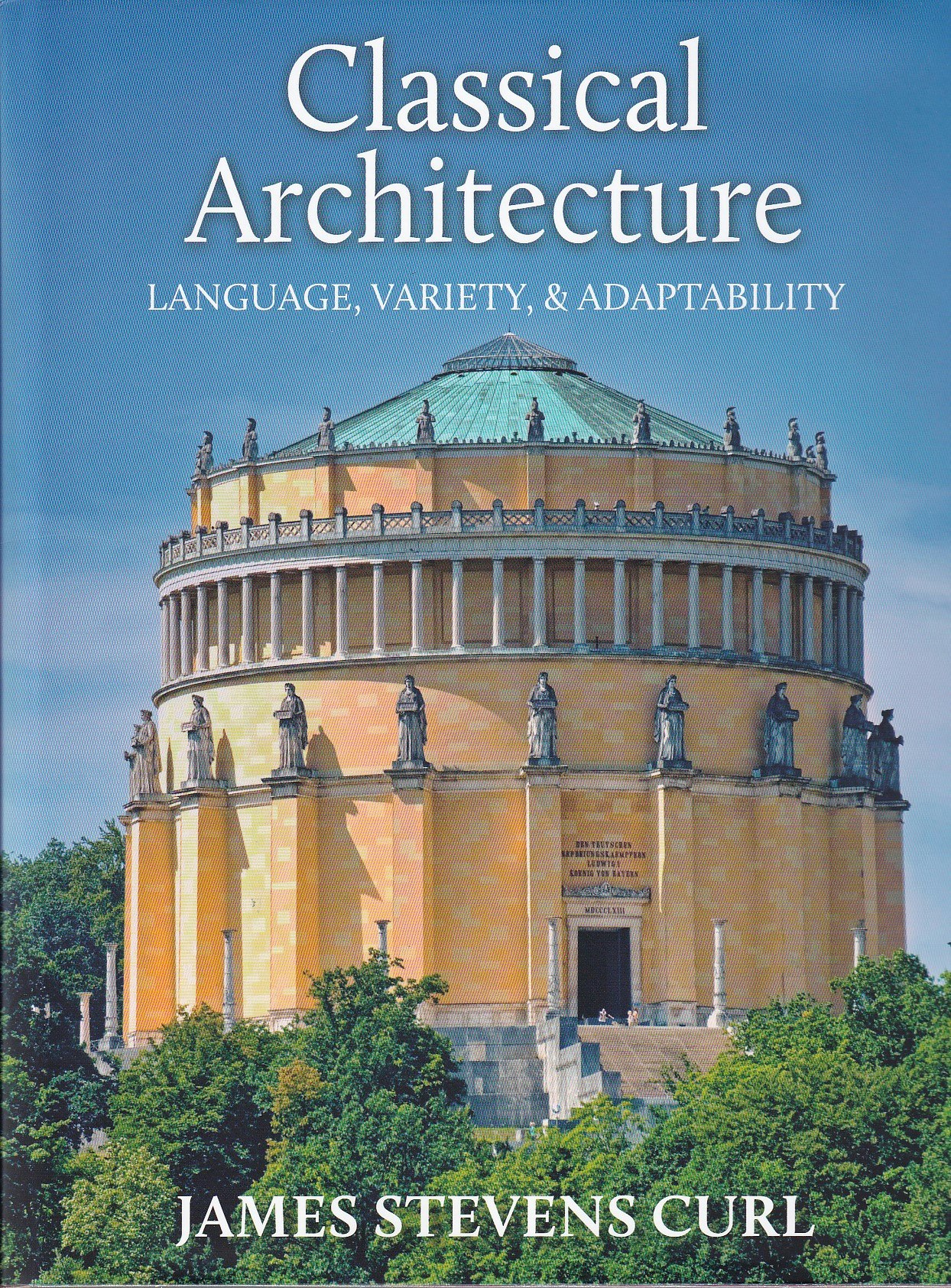

wrapper of Classical Architecture [2024] by James Stevens Curl).

I deliberately chose the Befreiungshalle (Hall of Liberation), set high on the Michelsberg, near Kelheim, in Bavaria, to grace the front of the wrapper of my recent book, Classical Architecture: Language, Variety, & Adaptability, which John Hudson has just brought out in a softback edition (ISBN: 978 1 7398229 5 8 [the hardback was published last year]). I did so because not only is it a masterly work of real architecture, created for King Ludwig I of Bavaria (r.1825-48) by one of the greatest architects of the 19th century, Leo von Klenze (1784-1864), but its ultra-refined Classical language commemorates, with supreme dignity and restraint, what the Germans call the Wars of Liberation against the French. The exterior of the circular drum is deceptively simple, but highly sophisticated, with 18 buttresses supporting colossal female figures, emblems of different German provinces, above which is a Roman Doric colonnade with 72 columns, and at the very top are 18 trophies.

The interior, lined with coloured marbles, is breathtakingly beautiful, and features 34 statues of Victories in Carrara marble carved in the studio of Ludwig Michael von Schwanthaler (1802-48), closely supervised by Franz Xaver Schwanthaler (1799-1854). Between each pair of Victories is a bronze shield made from captured French guns, and these bear the names of battles won. Above the arcades (the arches are segmental) are the names of 16 German generals on white marble tablets. The great building was inaugurated on the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig, otherwise known as The Battle of the Nations, or the Völkerschlacht, of 16-19 October, 1813, the largest battle on European soil before the war of 1914-18.

The German for “battle” is Schlacht, a word singularly appropriate for that mighty event, for a Schlachter is a butcher or slaughterer, and schlachten means kill, slaughter, slay, massacre, or butcher: it is estimated that there were around 100,000 killed, wounded, and missing over those three momentous days, when the armies of Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Sweden faced the troops commanded by Napoléon (and those were not just Frenchmen, but Poles, Germans from the Confederation of the Rhine, Italians, and others). There were three monarchs of the Coalition present: Tsar Alexander I of Russia (r.1801-25), King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia (r.1797-1840), and Kaiser Franz I of Austria (r.1804-35). Commanders on the Coalition side included, for Austria, Karl Philipp, Fürst zu Schwarzenberg (1771-1820), for Prussia, Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (1742-1819—Fürst von Wahlstadt from 1814), and for Sweden, Crown Prince Karl Johan Bernadotte, who was to become King Karl XIV Johan of Sweden and Karl III Johan of Norway (r.1818-44). Bernadotte (who had once been Jean-Baptiste-Jules Bernadotte [1763-1844] and a Marshal of France under Napoléon) was not the only one who changed allegiances in the course of the Napoleonic Wars: during the Völkerschlacht many Germans in Napoléon’s forces, mostly Saxons and Württembergers, defected to join the Coalition. The British were also involved at the Battle of Leipzig, for there was a Rocket Brigade commanded by Captain Richard Bogue (1782-1813) attached to Bernadotte’s army and, of course, Britain provided massive financial support for the Coalition. Bogue’s Brigade operated lethal rockets which had been invented from 1808 by Sir William Congreve (1772-1828, 2nd Baronet from 1814), but Bogue himself was killed during the Battle.

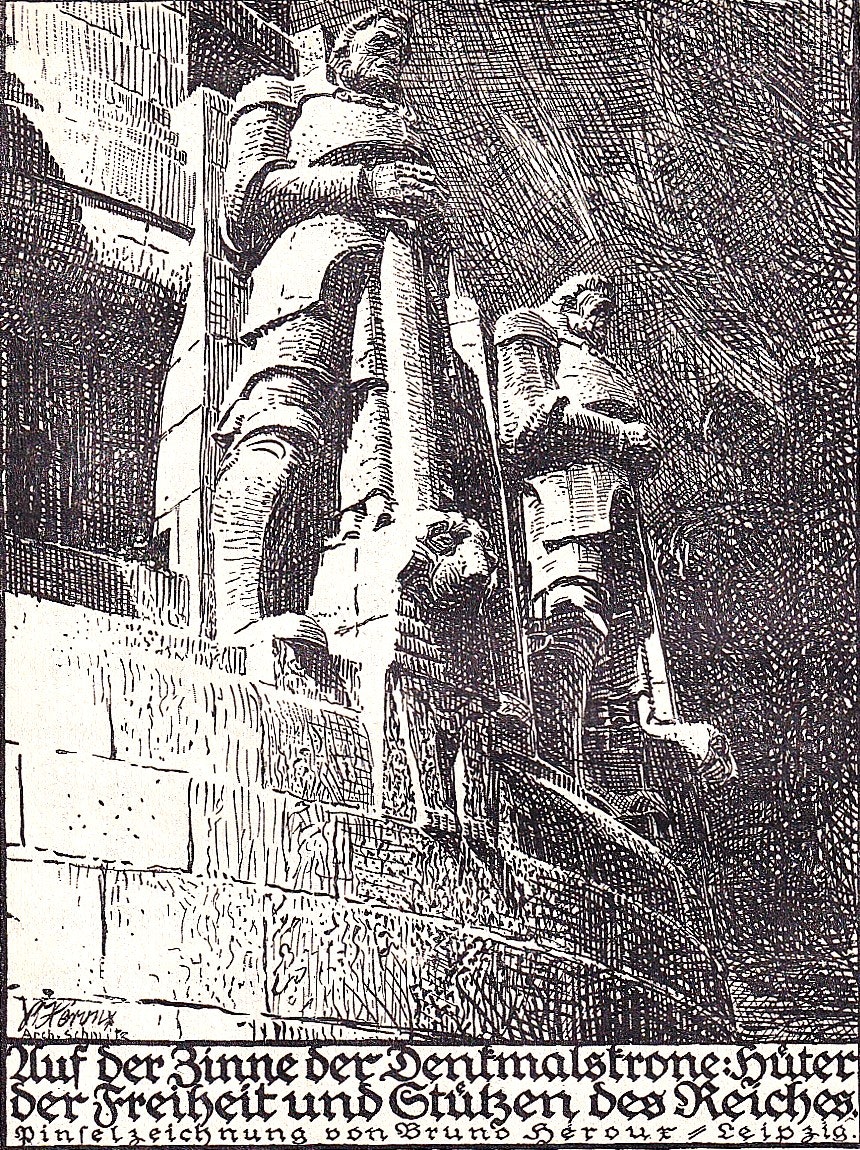

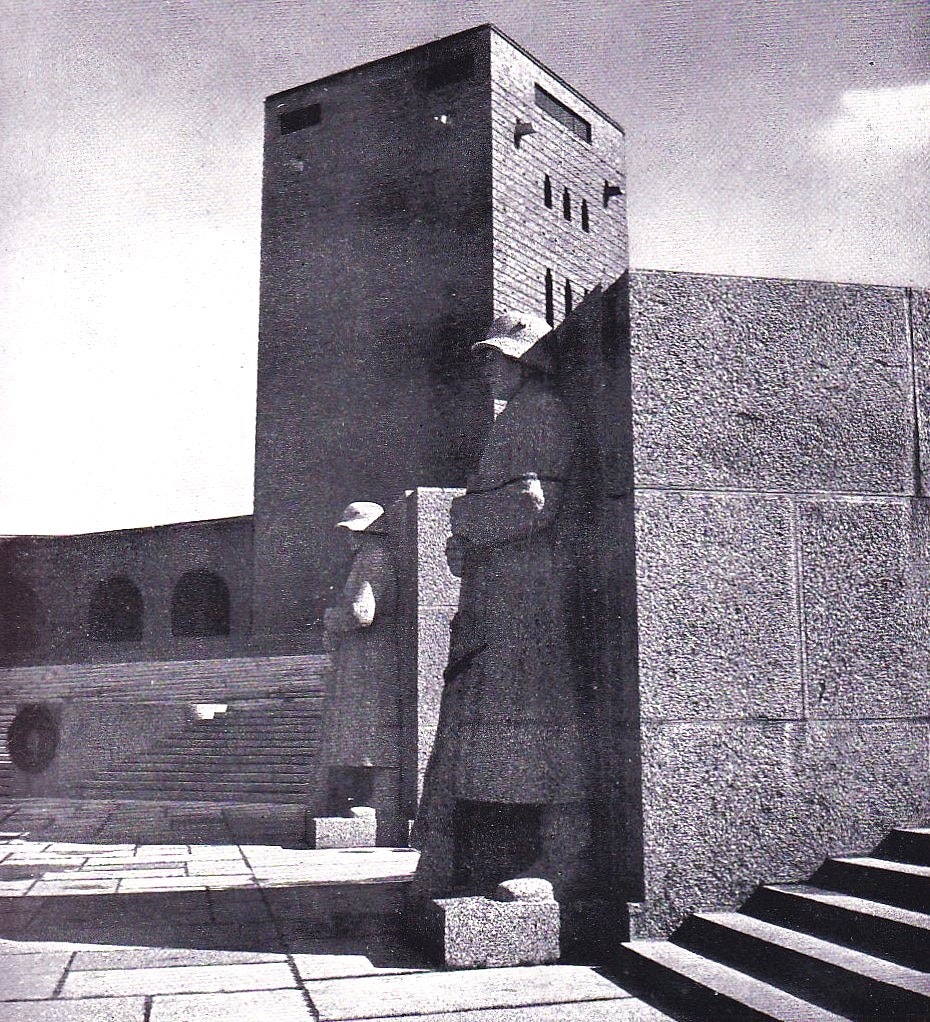

The centenary of the Battle of the Nations led to its commemoration by means of a massive monument (1896-1913) erected outside the city of Leipzig to designs by Bruno Schmitz (1858-1916): the contrast with the Befreiungshalle near Kelheim could not be more stark. Stylistically, this massive, forbidding pile-up, as noted by Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83), is

“a cyclopean granite structure of impressive outline, self-confident and threatening in mood”. Bruno Schmitz interpreted it himself: “The subject of the monument is the whole German people which rose and never rested in its struggle until the Corsican and his army were chased from German soil. Hence the monument also had to rise on a broad base in clear contours and to a great height, in vigorous forms, like a great nation rising.”

Indeed, but is it entirely without foundation to see in this Völkerschlachtdenkmal something of the menace of over-compensation, something that perhaps is detectable in the character of the Second Reich, especially under its bombastic, excitable, anti-Semitic Kaiser, Wilhelm II (r.1888-1918), whose appalling character-traits and disastrous influence on Germany have been so admirably dissected by the late John Charles Gerald Röhl (1938-2023)?

I have in my possession a remarkable volume, published in Leipzig in 1913, containing several illustrations by Bruno Héroux (1868-1944), which seem to emphasise the powerful, perhaps over-stated, brooding scale of the monument, and the thunderous, chunky, mighty sculpture (1906-13, by Franz Metzner [1870-1919], who replaced Christian Behrens [1852-1905] when the latter died relatively young) that adorns this truly heroic, Wagnerian masterpiece. Entitled Deutschlands Denkmal der Völkerschlacht, das Ehrenmal seiner Befreiung und nationalen Wiedergeburt (Germany’s Monument to the Battle of the Nations, the War Memorial to its Liberation and National Rebirth), it was edited by Rudolf Alfred Spitzner (1865-1937). The book was given to me by my colleague, Johann Georg, Graf zu Solms-Rödenheim und Assenheim (b.1938), many years ago, when we worked together as part of the Erasmus educational programme, a scheme I held in high regard, for it enriched and nurtured the minds of many of our students.

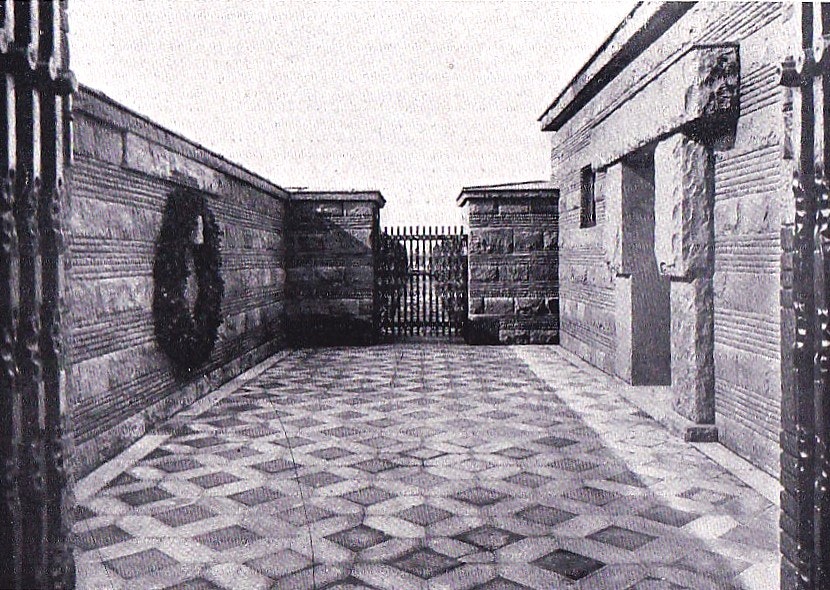

After the defeat of the Central Powers in 1918 and the collapse of the German Empire in the aftermath of that ruinous disaster for Europe as a whole, the German war cemeteries in Belgium are markedly understated. Not only were the Germans given rather small plots in which to bury their war dead in Belgium (contrasted with the generous acres provided for the British and French casualties), but a certain reticence had to be observed, for obvious reasons. The Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (German War Graves Commission) was responsible for the very moving design of the German War Cemetery at Langemarck, near Ieper, in Belgium, where the dead lie in largely natural surroundings approached through a rugged, chunky sandstone entrance. It was designed by Robert Tischler (1885-1959), who headed the design-team of the organisation from 1926 to 1958. Tischler and his colleagues were also responsible for the U-boat Möltenort memorial at Heikendorf, near Kiel, inaugurated in 1930: it has since been renovated several times, and now includes commemoration of the U-boat dead of the Second World War, as well as those sailors who served the Bundesrepublik.

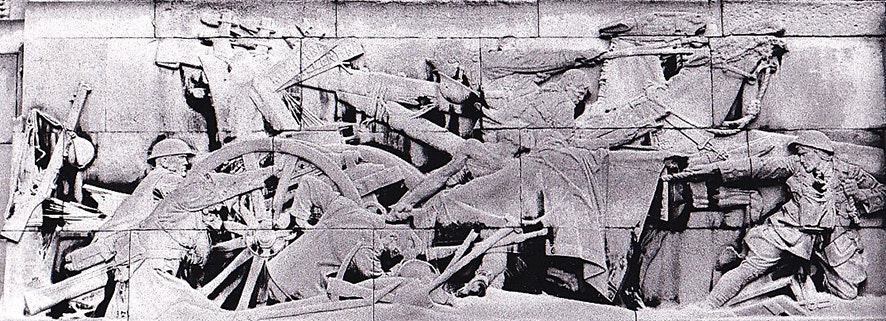

Sledmere, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, is one of the most perfect examples of an English estate village, created under the ægis of the Sykes family from the later 18th to the middle of the 20th century. Despite the mixture of styles and materials, it really works very well, and is rather pleasing in æsthetic terms. Before the First World War, Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes (1879-1919—6th Baronet from 1913) realised that should hostilities break out in Europe, skilled drivers would be needed to handle the horse-drawn transport, and so set up the Waggoners’ Special Reserve, drawing on farm-workers from estates in the Yorkshire Wolds. Some 1,200 men joined, with the result that when war broke out in August 1914 they were hurriedly called up, just when they were needed most at harvest-time, causing real problems on the land. At the end of the war, Sykes designed a memorial to his Waggoners to be erected in a prominent position at Sledmere, and this was duly erected, with carvings showing a history of the Special Reserve from its foundation to service on the Western front cut by Carlo Domenico Magnoni (c.1871-1961). In The Buildings of England volume on York and the East Riding Pevsner unaccountably refers to these carvings as “curiously homely”, carried out with “great skill and subtlety’. They seem to me, however, to be nothing of the sort, but rather crude caricatures of brutality and beastliness, depicting snarling Germans burning churches and slaughtering women, their expressions obscenely comical and exaggerated. This work, however, does suggest the visceral hatred stirred up in that war, a hatred that arguably made it possible for it to continue for so long, and there is no doubt that German cack-handed, blundering diplomacy, and undoubted atrocities, such as the shooting of Nurse Edith Louisa Cavell (1865-1915) and the burning, in August 1914, of the ancient library at the University of Leuven, handed the Entente Powers extremely valuable gifts in terms of propaganda disasters.

It is salutary to compare the quality of the Sledmere sculpture with that of the Royal Artillery Memorial, Hyde Park Corner, London (1921-5), designed by the firm of Adams, Holden, & Pearson (in this case largely Lionel Godfrey Pearson [1879-1953]), with vigorous sculpture by Charles Sargeant Jagger (1885-1934). Indeed, the reliefs are masterly, free from either sentimentality or caricature, and have the liveliness yet the control of an Assyrian hunt or a Hellenistic battle-scene: but they are consciously and successfully put together as highly considered, carefully structured compositions, of great power, showing the real thing in the rough, yet stylised sufficiently to work as æsthetically satisfying works of art.

To return to the Continent, one of the most dramatic events of the early 15th century was the utter defeat in 1410 by Poles, Lithuanians, and others (including Tatars) of the Teutonic Knights of St Mary’s Hospital at Jerusalem (Der deutsche Orden), the powerful military and religious Order which played a vital role in the Drang nach Osten by which Prussia was conquered and towns and fortresses were established throughout the newly acquired territories. No fortress was greater than the hugely impressive Marienburg, now Malbork in Poland, wonderfully restored to its glory by the Poles themselves. The Order had founded important towns such as Thorn (now Toruń in Poland, and named after Toron in Palestine), and the Order’s catastrophic defeat (despite the presence of English archers in its forces) at Grunwald (called Tannenberg by the Germans) created a profound dent in the German psyche.

When war broke out in 1914 the German plan was to knock out France with overwhelming numbers of troops before the Russians got their act together and attacked in the east. The Belgians, unsurprisingly, objected to German armies marching through their country in contravention of treaty obligations, and bravely resisted, fortified by the arrival of British forces and the support of the French. Not only were the Germans unable to break through at Ieper, but, despite the ferocity of their attack westwards, ran into serious trouble at the Marne, and by that time had sustained very severe losses (so severe in fact that the true numbers were concealed from the people as long as possible). Furthermore, the Russian steamroller started moving sooner than expected, and two armies, one commanded by Paul Georg Edler von Rennenkampf (1854-1918) and the other by Aleksandr Vasilyevich Samsonov (1859-1914), invaded East Prussia. This situation caused considerable consternation, and the German General in charge (Maximilian Wilhelm Gustav Moritz von Prittwitz und Gaffron [1848-1917]) was hurriedly replaced by Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und Hindenburg (1847-1934) with General Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (1865-1937) as his Chief of Staff. Had the Russians gained a victory in that region of the Masurian Lakes, the effect on German morale would have been catastrophic, for it would have been seen as a repeat of the disaster of 1410. Thanks to the brilliance of Hermann Karl Bruno von François (1856-1933) and Carl Adolf Maximilian Hoffmann (1869-1927), that disaster was transformed into a stunning victory, although Ludendorff’s jealousy ensured that von François never received proper credit. But Graf Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke (1848-1916), Chief of the German General Staff, fearing catastrophe in the east, sent forces needed in the west to reinforce troops fighting in East Prussia, which no doubt heartened Hindenburg, but, added to the enormous losses of men already sustained in the west, caused the beginning of the stalemate of the ensuing four dreadful years of trench warfare. So although Tannenberg was a great victory for the Germans, when their advance was blocked at the Marne a swift resolution in the west slipped from their grasp, so Moltke’s action may have contributed to the failure of the German plan, although a further success against the Russians was the winning of the Battle of the Masurian Lakes in September 1914, leading to the driving of all enemy forces out of German territory. These impressive military triumphs led to the elevation of Hindenburg, the “Wooden Titan”, as a national, almost deified hero, and the Hindenburg-Ludendorff team acquired a mystical status that deliberately obscured the real authors of the victories, Hoffmann and von François. Hoffmann was particularly irritated by this, and was scathing about Hindenburg’s alleged role in the victories. It should also be remembered that, later, Hindenburg made the fatal mistake of entrusting the future of the Fatherland to Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) in 1933.

After the war, a huge monument to the battle was erected in 1927 about a mile to the west of Hohenstein (now Olsztynek, Poland) to designs by Walter (1888-1971) and Johannes (1890-1975) Krüger: it resembled an octagonal fortress, with eight massive towers between which were curtain-walls. Later, the mausoleum of Hindenburg was constructed within its walls, flanked by tomb-chambers containing the remains of 20 unknown German soldiers who had fallen at Tannenberg, but as the Red Army advanced in 1945, Hindenburg’s coffin was removed and brought west, and the monument was partly dynamited by the retreating Germans. It was completely destroyed by the Poles in 1949. So the Tannenberg monument had many resonances with the histories of both Germany and Poland, both ancient and relatively recent. It should be remembered that Poles fought with Napoléon, hoping the French would help them to regain something of the independence they had lost when their country was partitioned between Prussia, Russia, and Austria in 1795, but they also fought in the armies of those three States, including 1914-18, although the war did not end for many Europeans or others in 1918 and indeed dragged on well into the 1920s. A poignant, yet understated, dignified reminder of this is the memorial in Litewski Square, Lublin, to the unknown warrior of the 1914-1920 struggles.

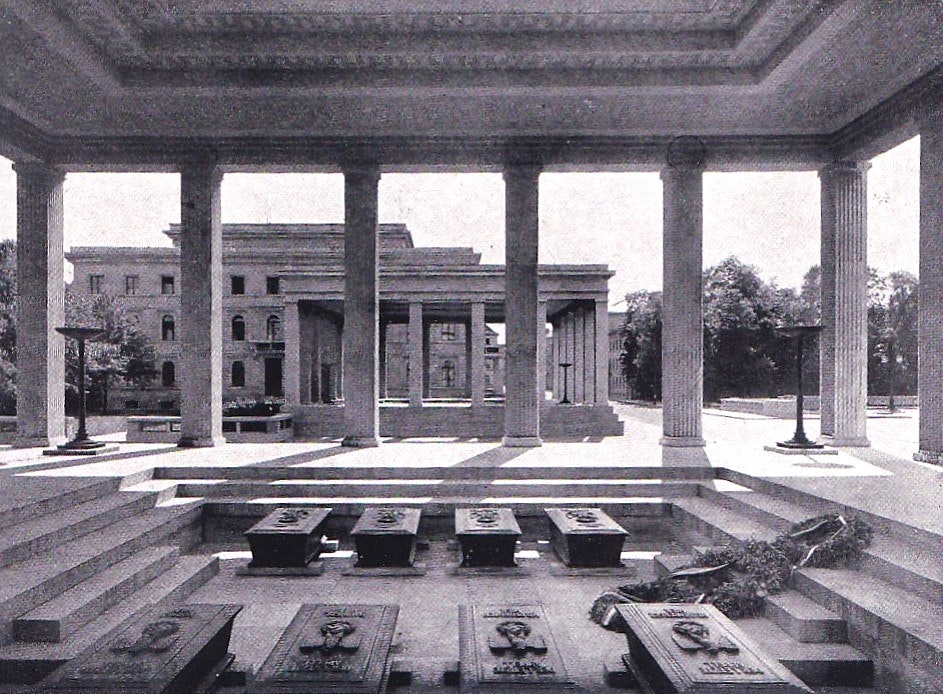

There are sometimes conflicts between æsthetics and commemoration. In Munich, the Bavarian capital, for example, the fine Neo-Classical Königsplatz was planned in the early years of the 19th century, and acquired its finest buildings when Leo von Klenze was called to the city by Crown Prince Ludwig (1786-1868—later King Ludwig I) in 1816. Klenze’s Glyptothek (1816-31), built to house Antique sculptures, is a synthesis of Greek, Roman, and Renaissance styles, but his Propyläen (1846-60) fuses Græco-Egyptian pylon-towers with severe Greek Doric porticoes. Opposite the Glyptothek across the square stands what was the Kunstaustellungs-Gebäude by Georg Friedrich Ziebland (1800-73), with its Corinthian portico, erected 1838-45. Now this left the last, eastern side of the square unfinished, but in 1933-7 it was filled by the two large buildings known as the Führer-Bau (containing a congress-hall and work-rooms) and the Verwaltungs-Bau (administrative offices), and the two severe Ehrentempel (temples of honour) structures, all erected by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party to designs by Paul Ludwig Troost (1879-1934).

The Ehrentempel were really open canopies supported on square fluted columns sheltering the tombs of the 16 National Socialists killed in the failed “Beer-Hall Putsch” of 1923. Erected in 1935, the temples were destroyed in 1947: the bodies had been removed and disposed of elsewhere in 1945. The temples certainly helped to successfully complete the square, and, perhaps once cleansed of their inhabitants and associations, the actual columns and roofs could have remained, perhaps re-dedicated to remembrance of the calamity that was the 12-year reign (yes, only 12 years!) of Nazism. It should also be remembered that the National Socialists intended to commemorate German “sacrifice and victory” with powerful monumental memorials in the lands conquered, and numerous designs for gigantic smoking cones, temple-like structures, mounds, and Totenburgen (fortresses of the dead) were made, many very impressive indeed, especially works by Wilhelm Kreis (1873-1955).

But how are atrocities to be commemorated? The difficulties are obvious when trying to face up to monstrous, industrialised mass-killings, such as those carried out in the vile extermination camps of Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek, and the rest of those abominations. Somehow, the blocky masses so often employed are too inarticulate for the job, and one feels rather let down, when something rather more powerful needs to be said. On the other hand, a recent memorial, commemorating the killing, carried out with extreme cruelty, of around 100,000 Poles by Ukrainians, and the destruction of numerous towns and villages, between 1942 and 1947 in south-eastern Poland, notably the districts of Volhynia, Eastern Galicia, Polesie, and the Lublin region, is shocking in its imagery, and pulls no punches. The sculptor, Andrzej Piotr Pityński (1947-2020), created a stark memorial to those terrible events: it consists of a large Polish eagle, with the names of destroyed settlements on its wings, being consumed by fire, with whole families being butchered, heads of the murdered on spikes, and, in the centre, a baby impaled on a pitchfork set within a void in the form of a Latin cross. It was erected in 2024 at Domostawa, not far from one of the main roads, that connecting Lublin and Rzeszów: several towns turned down offers to have it erected within them, due to the controversially unequivocal depictions of murderous savagery, and the Polish government also distanced itself from the campaign to have it erected. There were suggestions that it should be toned down, such as having the impaled infant removed, but the sculptor was adamant it should not be tinkered with. In August 2025 it was vandalised with paint and a slogan using the Cyrillic alphabet, but at the time of writing the jury is still out as to who might be responsible.

A presence, a scale, a slight overstatement, to some extent a formal stylisation, and an understanding of composition are among the essential ingredients in successful public commemoration, as is clear in the exemplar of the Royal Artillery Memorial in London. In the aftermath of the First World War many architects and artists rose to the occasion, but it has become clear to me, having travelled the length and breadth of the Atlantic Archipelago, that many others singularly failed to do so. Allegorical figures mean little to the average person, while lugubrious, sexless angels, naked figures affecting Classical poses, and mock-heroic images can attract ridicule or induce a sense of outrage in anyone who knows anything of the deadly, numbing, dehumanising horrors of warfare.

In 1997, I recall being appalled by the outpouring of what seemed to me to be irrational, national mass-hysteria after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales (1961-97), and I know I was not alone in feeling revolted, extremely uncomfortable, and profoundly embarrassed by what was going on. I suppose that reflects my abhorrence of mobs, hysterical crowds, and the potential for terrible destruction of which they can be capable. Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) said, with truth, that the majority never has right on its side, although Horace Walpole (1717-97) admitted that our supreme governors are the Mob, yet I have always been leery of doing what the Mob wishes to do. Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926), in 1918, said that as a rule the majority was wrong, and Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805) ruefully admitted that with Stupidity (Dummheit) the deities themselves struggle in vain, indeed a sobering thought, for if the Gods cannot control it, who can? Rabble-rousers, perhaps, ancient thunderers, and purveyors of cant seem able to make use of mobs for their nefarious ends.

Twenty years after her death, a statue commemorating Diana was commissioned from Ian Rank-Broadley (b.1952), and unveiled in the Sunken Garden of Kensington Palace in 2021. This group seems to my eye to be drippily sentimental and feeble, perhaps the epitome of mawkish Diana-worship, and maybe therefore is some kind of appropriate memorialisation of that embarrassing outburst of exaggerated emoting that followed her death. But, looking at the sculpture again, its cringe-making aspects seem greater than ever, for it suggests to me, at least, some kind of quasi-religious, contemporary, suburban Madonna, clad in sensible clothes and shoes, doubtless to add to the “common touch” so valued by Diana’s admirers. But that does not make it great art, and I reckon that æsthetically it can be considered a failure.

What Sargeant Jagger would have made of it must remain in the misty realms of agreeable fantasy.