“I REMEMBER the moment I first saw Nick. He was very tall – but kind of apologetically tall.”

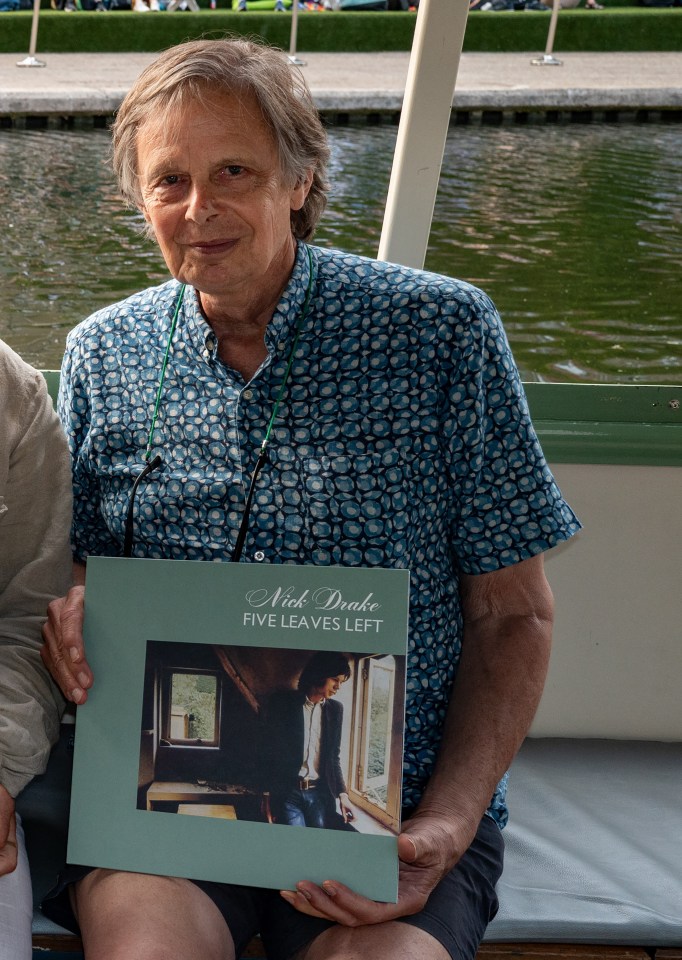

Legendary producer Joe Boyd is casting his mind back to January 1968, to the day “very good-looking but very self-effacing” Nick Drake dropped a tape off at his London office.

“He stooped a bit, like he was trying not to seem as tall as he was.

“It was wintertime and there were ash stains on his overcoat. He handed me the tape and trundled off.

“My first encounter with Nick’s music was, most likely, that same evening or possibly the following one.”

Boyd, an American who became a central figure in the late Sixties British folk-rock boom, was 25 at the time.

Drake was 19. He cut a striking figure — lanky with dark shoulder-length hair framing his boyish features.

Through his company, Witchseason Productions, Boyd came to helm stellar albums by Fairport Convention (with Sandy Denny), John Martyn, Shirley Collins and The Incredible String Band.

But there was something indefinably mesmerising about those three songs passed to him by the quiet teenager who studied English Literature at Cambridge University.

As Boyd switched on his “little Wollensak reel-to-reel tape recorder”, he was captivated by Drake’s soft but sure tones, allied to his intricate fingerpicking guitar. “I think the songs were I Was Made To Love Magic, Time Has Told Me and The Thoughts Of Mary Jane,” he says. “From the first intro to the first song, I thought, ‘Whoa, this is different’.”

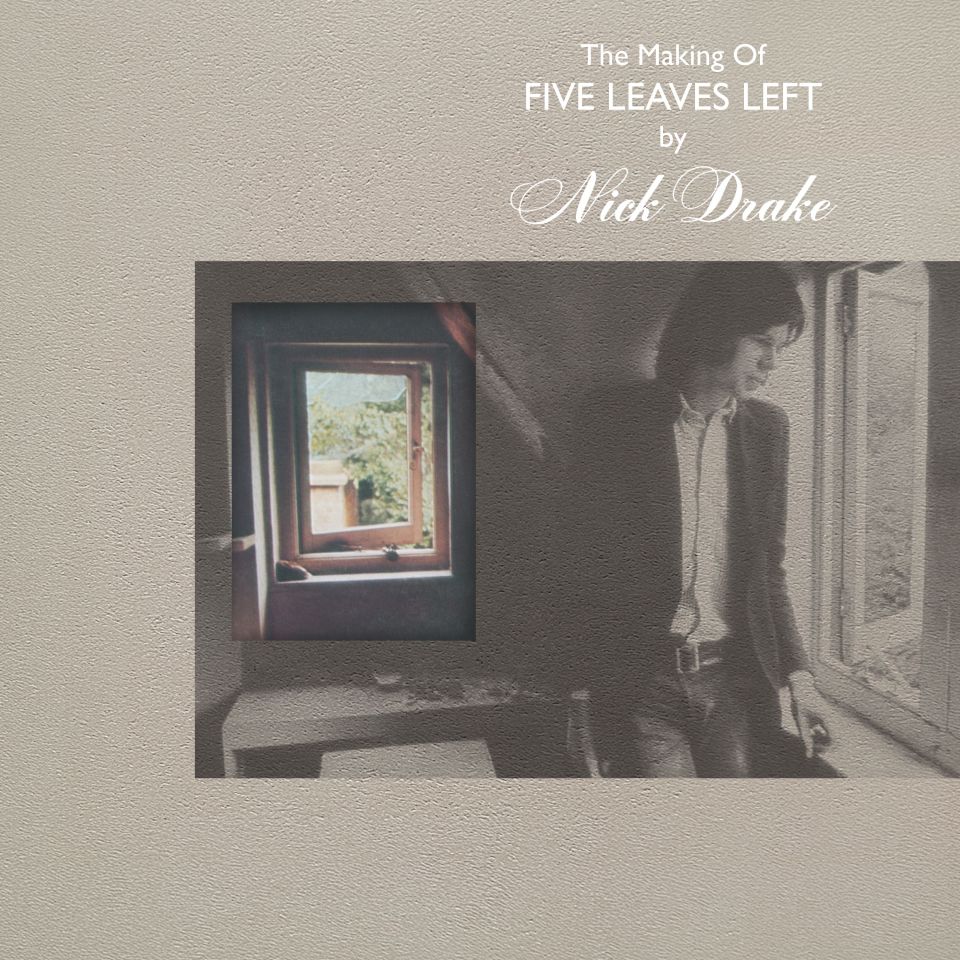

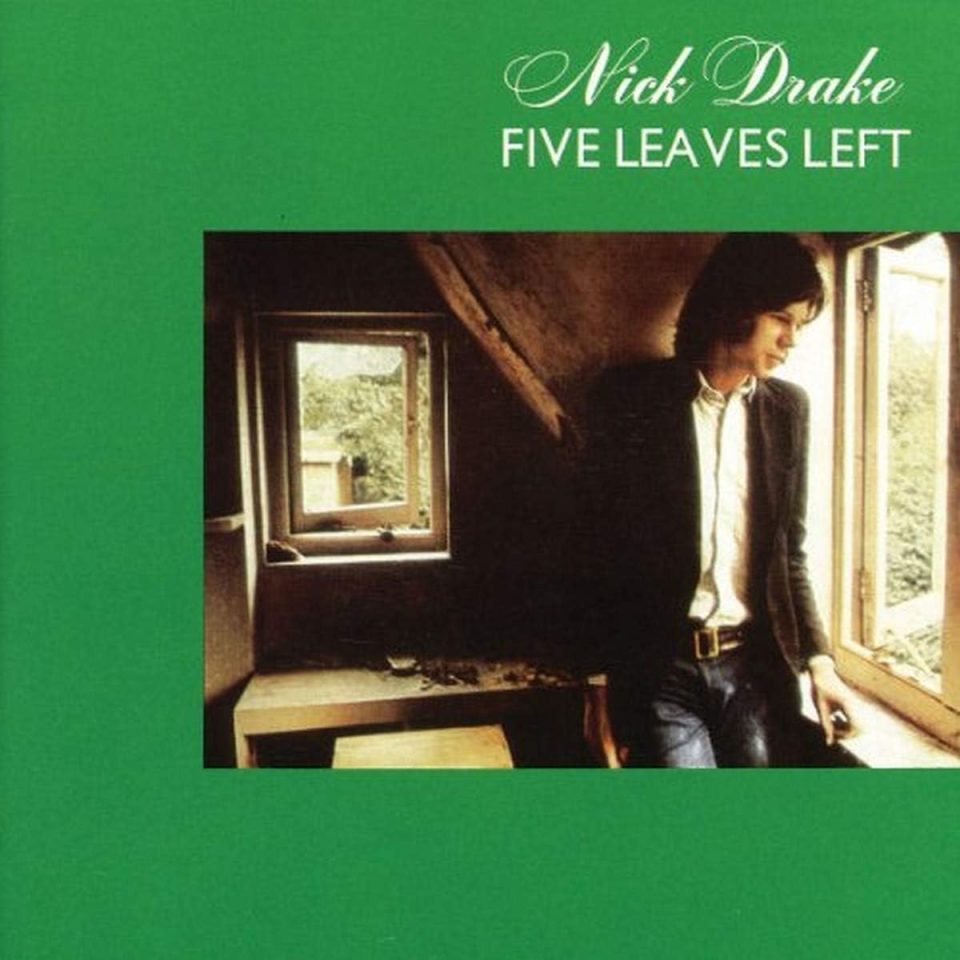

I’m speaking to Boyd to mark the release of a beautifully curated box set, The Making Of Five Leaves Left, a treasure trove of demos, outtakes and live recordings.

Rounding it off is the finished product, Drake’s debut album for Chris Blackwell’s fabled Island Records pink label.

In 2025, the singer’s status as one of Britain’s most cherished songwriters is assured.

A troubled soul, Drake died aged 26 in 1974 from an overdose of antidepressants, never enjoying commercial success in his lifetime, never knowing how much he would be appreciated.

But Boyd, now 83, had no doubts about the rare talent that he first encountered in 1968.

He picks up the story again: “Ashley Hutchings, the Fairport Convention bass player, saw Nick playing at The Roundhouse [in Camden Town, North London] and was very impressed.

“He handed me a slip of paper with a phone number on it and said, ‘I think you’d better call this guy, he’s special’.

“So I called and Nick picked up the phone. I said, ‘Do you have a tape I could hear?’. He said, ‘Yes’.”

Boyd still didn’t hold out too much hope, as he explains: “I was very much a blues and jazz buff. I also liked Indian music.

“White middle-class guys with guitars were never that interesting to me — Bob Dylan being the exception that proves the rule.

“But Nick was something else. He wasn’t really a folk singer at all.”

Boyd describes Drake as a “chansonnier”, a French term for a poet singer who performs their own compositions, often drawing on the themes of love and nature.

He says: “I’m always a bit bemused when I go into a record store — one of the few left — and see Nick filed under folk. He’s unclassifiable and that’s one of the reasons he endures.”

To Boyd, Drake’s enduring appeal is also helped “by the fact that he didn’t succeed in the Sixties”.

“He never became part of that decade’s soundtrack in the way Donovan or [Pentangle guitarist and solo artist] Bert Jansch did.

“So he was cut loose from the moorings of his era, to be grabbed by succeeding generations.”

Drake was born on June 19, 1948, in Rangoon, Burma [now Myanmar], to engineer father Rodney and amateur singer mother Molly. His older sister Gabrielle became a successful screen actress.

When Nick was three, the family moved to Far Leys, a house at Tanworth-in-Arden, Warks, and it was there that his parents encouraged him to learn piano and compose songs.

I’m always a bit bemused when I go into a record store — one of the few left — and see Nick filed under folk. He’s unclassifiable and that’s one of the reasons he endures.

Joe Boyd

Having listened to the home recordings of Molly, Boyd gives her much credit for her son’s singular approach.

He says: “When you hear the way she shaped her strange chords on the piano and her sense of harmony, it seems that it was reverberating in Nick’s mind.”

When Drake gave him those three demos, recorded in his room at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, Boyd “called the next day and said, ‘Come on in, let’s talk’.”

During the ensuing meeting, Drake said: “I’d like to make a record.”

He was offered a management, publishing and production contract.

Just as importantly, he had found a mentor in Joe Boyd.

What you hear on the box set is the musical journey leading up to the release of Five Leaves Left in July 1969.

The set was sanctioned by the Estate Of Nick Drake, run on behalf of his sister Gabrielle by Cally Callomon, but only after two remarkable tapes were unearthed.

- His first session with Boyd at Sound Techniques studio in March 1968 — found on a mono listening reel squirrelled away more than 50 years ago by Beverley Martyn, a singer and the late John Martyn’s ex-wife.

- A full reel recorded at Caius College by Drake’s Cambridge acquaintance Paul de Rivaz. It had gathered dust in the bottom of a drawer for decades.

Boyd says: “I have never been a big enthusiast for these endless sets of demos and outtakes — so I was highly sceptical about this project.

“But when my wife and I were sent the files a few months ago, we sat down one evening and listened through all four discs.

“I was tremendously moved by Nick. You can picture the scene of him arriving for the first time at Sound Techniques.

“This is what he’s been working for. He’s got his record deal and here he is in the studio. I was stunned.”

In pristine sound quality, the first disc begins with Boyd saying, “OK, here we go, whatever it is, take one.”

Drake then sings the outtake followed by some of his best-loved songs — Time Has Told Me, Saturday Sun, Day Is Done among them.

It’s just man and guitar, recorded before musicians such as Pentangle’s double bass player Danny Thompson and Fairport Convention’s guitarist Richard Thompson (no relation) were drafted in.

Boyd continues: “The trigger for those recordings, that first day in the studio, was wanting our wonderful engineer John Wood to get a feel for Nick’s sound.

“Nick was wide awake and on it. He was excited about being in a studio and he wanted to impress.”

All these years later, one song in particular caught Boyd’s attention — Day Is Done.

“He takes it more slowly than the final version. This gives him time to add more nuance and the singing is so good.”

Back then, as Five Leaves Left took shape, Boyd witnessed the sophisticated way Drake employed strings, oboe and flute.

Inspired by subtle orchestrations on Leonard Cohen’s debut album, Boyd had drafted in arranger Richard Hewson but it didn’t work out.

“It was nice, but it wasn’t Nick,” he affirms.

When Drake suggested his Cambridge friend Robert Kirby, a Baroque music scholar, everything fell into place.

Boyd says: “Nick had already been engaging with Robert about using a string quartet but had been hesitant about putting his ideas forward.”

SUBTLE ORCHESTRATIONS

The producer also recalls being “fascinated by the lyrics — the work of a literate guy”.

“I don’t want to sound elitist but Nick was well educated. British public school [Marlborough College] and he got into Cambridge.

“Gabrielle told me he didn’t like the romantic poets much. But you feel that he’s very aware of British poetry history.”

This is evident in the first lines of the opening song on Five Leaves Left — “Time has told me/You’re a rare, rare find/A troubled cure for a troubled mind.”

“When I think about Nick, I think about the painting, The Death Of Chatterton,” says Boyd. “Chatterton was a young romantic British poet who died, I think, by suicide. You see him sprawled out across a bed.”

I ask Boyd how aware he was of Drake’s struggles with his mental health.

“It’s a tricky question because I was aware that he was very shy,” he answers. “Who knew what was going on with him and girls?”

Boyd believes there was a time when Drake was better able to enjoy life’s pleasures.

“When you read of his adventures in the south of France and in Morocco, it seems he was more relaxed and joyful.

“And when I went up to Cambridge to meet Nick and Robert Kirby before we did the first session, he was in a dorm.

“There were friends walking in and out of the room. There was a lot of life around him.”

Boyd says things changed when “Nick told me he wanted to leave Cambridge and move to London.

“I agreed to give him a monthly stipend to help him survive. He rented a bedsit in Hampstead — you could do that in those days.

“Nick started smoking a lot of hashish and didn’t seem to see many people. I definitely noticed a difference.

“He’d been at Marlborough, he’d been at Cambridge and suddenly he’s on his own, smoking dope, practising the guitar, going out for a curry, coming back to the guitar some more. He became more and more isolated and closed off”.

Boyd describes how Drake found live performance an almost unbearable challenge.

He says: “He had different tunings for every song, which took a long time. He didn’t have jokes. So he’d lose his audience and get discouraged.”

‘It still haunts me that I left the UK’

For Drake’s next album, Bryter Layter, recorded in 1970 and released in 1971, Boyd remained in charge of production.

Despite all the albums he’s worked on, including REM’s Fables Of The Reconstruction and Kate and Anna McGarrigle’s classic debut, he lists Bryter Layter as a clear favourite.

It bears the poetic masterpiece Northern Sky with its heartrending opening line – “I never felt magic crazy as this.”

Boyd says: “I can drop the needle and relax, knowing that John Wood and I did the best we could.”

However, he adds that it still “haunts me that I left for a job with Warner Bros in California after that. I was very burnt out and didn’t appreciate how much Nick may have been affected by my leaving”.

Drake responded to Boyd’s departure by saying, “The next record is just for guitar and voice, anyway”. Boyd continues: “So I said, ‘Well, you don’t need me any more. You can do that with John Wood’.”

When he was sent a test pressing of 1972’s stripped-back Pink Moon, he recalls being “slightly horrified”.

“I thought it would end Nick’s chances of commercial success. It’s ironic that it now sells more than his other two.”

Then, roughly a year after leaving the UK, Boyd got a worried call from Drake’s mum.

“Molly said she had urged Nick to see a psychiatrist because he had been struggling,” he says, with sadness, “and that he had been prescribed antidepressants.

“I know Nick was hesitant to take them. He felt people would judge him as crazy — a typically British response.”

Boyd again uses the word “haunting” when recalling the transatlantic phone call he made to Drake.

“I said, ‘There’s nothing shameful about taking medicine when you’ve got a problem’.

I know Nick was hesitant to take them [antidepressants]. He felt people would judge him as crazy — a typically British response

Joe Boyd

“But I think antidepressant dosages were way higher in those days than they became.

“Doctors didn’t appreciate the rollercoaster effect — how you could get to a peak of elation and freedom, then suddenly plunge back into depression.

“Who knows but it might have contributed to the feeling of despair Nick felt the night he took all those extra pills.”

Drake died at home in Warwickshire during the early hours of November 25, 1974.

As for Boyd, he made a lasting commitment to the singer who had such a profound effect on him. He says: “When I left, I gave my company to Chris Blackwell because there were more debts than assets — and he agreed to take on the debts.

“But I said, ‘I want it written in the contract that you cannot delete Nick Drake. Those records have to stay.

“I just knew that one day people would get him.”