This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

There are various spots in King Charles III’s garden at Highgrove where he remembers his friends. One is the Cottage Garden, in which a roughly tooled stone plinth supports a bust of Léon Krier. Elsewhere, a parade of royal heroes, from composer John Tavener to the ecologist Dame Miriam Rothschild, forms a kind of chorus line on the top of a wall. But Krier, who died on June 17, stands alone.

That is a signal honour: a sign of his importance to HM as the man who steered the development of the Duchy of Cornwall’s model development of Poundbury for 30 years. It is also appropriate. Krier, funny, immensely charming to his friends and no recluse — although he spent his last years on Mallorca — did not follow the herd.

Nor was he an obvious courtier. Those of us who knew him in the 1980s could hardly have predicted that he would become a figure of such influence, not just with the King but around the world. Ciudad Cayalá, his new city in Guatemala, is a dream of perfection — only better than a dream, being real.

Krier was that unfamiliar thing in British life: an intellectual. A Continental who spoke many languages — always, if his English was anything to go by — in the accent of his native Luxembourg, he was also a brilliant pianist. Architecture was his calling. After studying it at the University of Stuttgart, he joined the office of James Stirling, lauded for his genius in creating his own language of form and colour, in opposition to the prevailing drab, rectilinear orthodoxies of the Modern Movement.

That was in 1968, the year Stirling’s History Faculty building at Cambridge opened. Designed in the shape of an open book, with walls and centrepiece of glass, it was literally dazzling when the sun shone on it. But buckets were soon being positioned to catch the leaks from the cascade of windows overhead, whilst during the legendary summer of 1976 the temperature on upper floors regularly exceeded 50°C. (It is about to be refurbished at unimaginable cost in today’s more efficient materials.)

So much for starchitects — a term coined in the 1980s — who sacrifice practicality in their pursuit of the new. Most architecture of the time was not bold but deadly boring, which arguably seemed worse. Hence Krier’s pronouncement, paradoxical, utopian, absolute in its refusal to compromise with a fallen world: “I am an architect because I do not build.”

Instead of building, Leo — as everyone called him — taught at the chaotically creative Architectural Association and wrote books. As a polemicist, he stood in the tradition of A.W.N. Pugin, whose Contrasts of 1836 parodied the decadence of contemporary architecture through a series of drawn comparisons; the splendours of the medieval past, as Pugin imagined them, were juxtaposed with the moral poverty of the present. Krier had a similar ability to condense his arguments into drawings, often cartoon-like, which ridiculed his opponents.

He was a master of metaphor. Whereas Pugin was Gothic, Leo championed the values of Classicism, as practised by a small and persecuted sect of young zealots who resembled members of the early Church: they suffered daily professional martyrdom as their schemes were rejected, except by the occasional private client, and their opinions were lampooned by the establishment. Leo gave an intellectual rigour to their lonely attempt to be taken seriously.

Modernists, with their visceral hatred of tradition, decried Classicism as being fascist. Typically, Krier did nothing to defuse the argument by publishing a book on Albert Speer, Hitler’s favourite architect and a war criminal who had served 20 years in prison after the Nuremburg Trials. As a Jew, Krier loathed the Nazi regime but as a critic, he looked objectively at the work, independent of the moral failings of the man responsible for it. There may have been a touch of pour épater les bourgeois in his motivation. How else to explain it? The Speer book could have sunk his career.

Of course, at the time, there wasn’t much to sink. But that, somewhat in the manner of a fairy story, was about to change. Almost miraculously, a Prince appeared.

❂

In 1984, the future King Charles III spoke at a gala for the Royal Institute of British Architects at Hampton Court Palace. The RIBA was celebrating its 150th anniversary but rather than tickling their corporate tummy, Prince Charles kicked them in a tender place. In a never to be forgotten phrase, he likened a proposed extension to the National Gallery to a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”.

The speech not only torpedoed that project, subsequently replaced by the Sainsbury Wing. It exploded the fortress-like walls behind which the architectural profession had been sheltering. Previously, architects, like members of other professional bodies at the time, thought they knew best.

Krier was elated. He sent Charles details of a project for Washington, D.C. which, as he told me in an interview shortly before his death for my book King Charles III: 40 Years of Architecture, would have turned the American capital into a “kind of Classical marvel”. A couple of years later, Prince Charles opened a small but valiant exhibition called Real Architecture — funded, surprisingly, by a £500 grant from the left-wing GLC — to show work by the Classical architect John Simpson and his friends.

Meeting Krier, he said, “Let’s talk.” Krier was invited to become his consultant on architecture and urbanism. “Wow, my God,” he told me. “How could I refuse? And then we’d meet for six to seven months, always at strange times and places, like at 3am with some Russian princess in Chelsea … It had to be hush-hush. I became the consultant for Paternoster Square.”

Paternoster was Prince Charles’s next big thing, an attempt to overturn an overcrowded Modernist scheme to replace a 1960s Corbusian confection of walkways and tower blocks — redundant after only 20 years — next to St Paul’s Cathedral. Another speech was delivered, which slew the dragon of Modernism and enthroned Classicism next to the great national monument of Wren’s cathedral.

❂

In 1987, whilst Krier was in the United States working with Duany Plater-Zyberk on Seaside, Florida — an early demonstration of New Urbanism — a call came from the Prince of Wales. Krier was to be the masterplanner of Poundbury.

The first public consultation took place in a marquee beneath the tall trees of Poundbury Farm. Every inch the metropolitan, Krier arrived dressed for the South of France rather than Dorset, with a silk scarf knotted around his neck and hair from the same salon as Albert Einstein.

Having been allotted a mere 10 minutes, Krier took a vote from the audience and spoke for an hour. His relationship with the upper echelons of the Duchy of Cornwall was volatile. Being absolute in his values, he preferred to resign if a project went off course. How many times did he resign from Poundbury? No fewer than 17, I think. It says much for the King that he always succeeded in bringing him back into the fold. Unusually, there has only been one masterplanner at Poundbury for the 30 years it has taken to build — Leo.

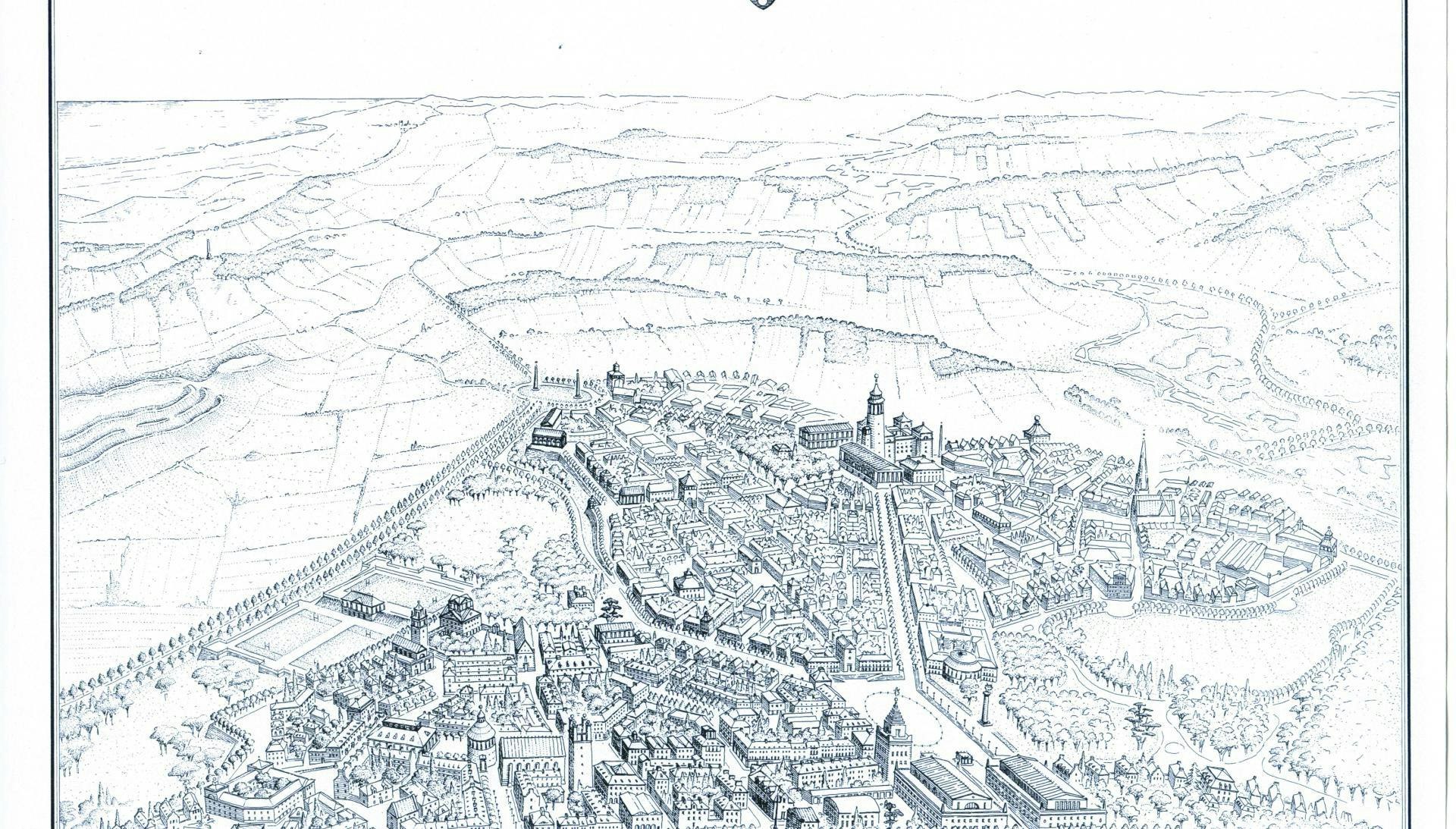

Krier’s masterplan seemed as foreign as he himself was. It was patterned after a Mediterranean town where people live close to one another. Concentrated humanity makes it buzz with life. Contrast this with a suburb where people have personal space — good for families with growing children but bad for the young, the elderly and anyone who prefers to have shops, cafes and services within easy reach.

Poundbury was to be an urban extension of Dorchester, somewhere that would be, for most purposes, a self-sufficient entity, rather than having to rely on facilities too far away to reach on foot. This was a revolutionary idea in terms of late-20th century planning.

Krier’s drawing showed public buildings, town squares and tree-lined avenues, like a modern-day Pienza sprung from the mind of a Renaissance pope. There would be no obvious financial return from some of these features.

This alone might have killed the scheme, given that the Duchy Council is made up of people experienced in land management and investing, and charged by Parliament with making an adequate return on the portfolio. Krier was able to persuade them that the long-term return from his approach would ultimately make more money for the Duchy than a conventional development. And it has.

Poundbury would be somewhere that inhabitants both lived and worked. This was another challenge to the planning orthodoxy of the day. So too was the idea that the needs of people on foot should come before car drivers. Cars were not banished — who in the countryside does not need one? — but kept off the streets and out of sight. Rather than facilitating the movement of traffic through the streets, streets were planned in such a way as to slow it down.

A third of the new housing would be affordable — only nobody would know where it was; because from the outside the affordable homes would look exactly the same as the homes sold at market prices, so there would be no stigma attached.

In addition, everything needed to support life would be only a stroll away. Walking is good for health, good for wellbeing and it builds community. When people are outside their houses and their cars, they are more likely to run into neighbours and enjoy those friendly interactions which are part of the joy of local life, when it is properly organised.

In the course of 30 years, Poundbury went through a number of different iterations, as ideas were tried, evaluated and revised. Architecturally, it may be too busy in parts; every classical or traditional architect that the King could think of was given a project. This made it something of an architectural zoo.

But time has worked its mellowing magic. The gloss of newness has rubbed off. It is strangely harmonious and — as even my wife agreed when we stayed there whilst I was researching my book — delightful to be in. No wonder the residents’ association has called itself “Love Poundbury”. Many people do.

Not all the credit for this is down to Krier. He worked with numerous architects, the engineer Alan Baxter, traffic consultants and the excellent West Dorset District Council. But the fundamental vision was and remains his. There has never been a time in my professional life when the government has not wanted to build more houses. What once seemed like a desirable objective has now become an urgent national priority.

Yet nobody, with one exception, has come up with a convincing model to show how they can be provided at scale. That exception was Léon Krier. Like the late Roger Scruton, he dared to use the “b” word — beauty. He knew that it improved people’s lives. He knew how to achieve it, too.