I can still remember May 21, 1982, as if it were yesterday. It was the launch date of The Hacienda, the Manchester dance club created by Factory Records, the world’s hippest ever independent label.

Everyone who was anyone was desperate for membership of an institution that was destined to go down in history as the driving force behind Manchester’s transformation from fading industrial giant to creative powerhouse.

Somehow my application was accepted and I received my membership card for FAC51, the catalogue number given to the club, in time to make the opening night.

The paint in the loos was still wet when ‘Mr Manchester’ Tony Wilson, the Factory founder who somewhat improbably doubled up as presenter of Granada Reports, the local regional TV news show, delivered his rambling welcome speech.

The celebrity guest Bernard Manning behaved true to type. Grotesquely fat, crude, and, frankly, racist, this Northern comedian – who had presumably been hired for his shock value – took one look around, turned to one of the organisers and said: ‘I’ve played some f***king sh*tholes in my time, but this beats the lot of them.’ With that he walked off stage, handed back his appearance fee and disappeared into the night.

Despite its thriving music scene, however, Manchester in the early 1980s was the living embodiment of the phrase: ‘It’s grim up north.’

For my final two years at university, I lived on a street on the outskirts of a condemned council estate in Hulme, known locally as ‘The Crescents’ after its series of curved brutalist concrete housing developments.

By the time I moved in, leaky roofs, poor insulation and an epidemic of drug-dealing – aided by the provision of so-called ‘walkways in the sky’ that enabled the local crime lords to easily give the slip to any police officers giving chase – had driven out most of the tenant families and those habitable flats that remained were rented to students at peppercorn rents.

The Crescents council estate in Hulme, Manchester, named after its series of curved brutalist concrete housing developments

The estate was demolished in the 1990s and has since given way to a £400million regeneration of Hulme

Virtually everyone I knew on the estate, except me, was burgled at least once. Walking home one evening, I was overtaken by a pack of at least ten stray dogs. And in the summer of 1981, residents of my block woke one day to the sight of a dead body on the grass verge opposite.

Ten years later, the city fathers finally saw sense and The Crescents were demolished. Visiting the area this week was a revelation. One of Britain’s most disastrous experiments in social housing has given way to an attractively landscaped area dotted with the sort of apartment blocks and houses calculated to swell the heart of the most discerning hipster.

And the £400million regeneration of Hulme is just one example of a wider renaissance that has transformed England’s second city.

Figures released by the Office for National Statistics last month showed that productivity, one of the most important economic indicators, has risen steeply in Greater Manchester since 2021, despite flatlining across much of the rest of Britain.

And while the country at large recorded an anaemic growth rate of 0.3 per cent in the last quarter, Manchester is growing at a rate of 2.5 per cent a year.

A city centre, which accommodated an estimated 300 residents as recently as 40 years ago, now has a population of 100,000 thanks to a development boom which has seen the skyline change out of all recognition, making it resemble a temperate Dubai.

Between 2018 and 2024, 27 high-rise towers with space for more than 60,000 people were built across Manchester and there are a further 20 under construction, with 51 more at the planning stage.

Only last month, Salford councillors voted to approve plans for Viadux 2, a £350million, 895ft residential tower, whose 76 floors will contain 452 apartments and a 160-bed hotel operated by Nobu, a brand part-owned by Robert De Niro.

Manchster’s city centre, which accommodated an estimated 300 residents as recently as 40 years ago, now has a population of 100,000 thanks to a development boom which has seen the skyline change out of all recognition

Manchester’s building boom was kick-started by a massive IRA bomb that ripped the heart out of the city in 1996

Once completed, it will become the tallest building in Greater Manchester and the third tallest in the country, behind the Shard and Horizon 22, which are both in London.

The rise of many British city centres is rooted in the redevelopment of areas destroyed by Second World War air raids but, in Manchester’s case, the building boom was kick-started by a massive IRA bomb that ripped the heart out of the city in 1996.

The explosion, caused by a 3,300lb lorry bomb, was the biggest since the war, and caused colossal damage to hundreds of shops and offices within a half-mile radius but – thanks to a telephone warning – no one was killed.

The devastation sparked a £1.2billion redevelopment of central Manchester and led to that spate of high-rise developments, with the result that there are now no fewer than 34 towers in Manchester that are more than 100 metres high. People have even taken to calling the skyscraper cluster at Deansgate Square ‘Manc-hattan’.

One tower that has become a magnet for online influencers thanks to apartments that offer floor-to-ceiling windows with panoramic views across the city is a 47-floor behemoth called ‘Cortland at Colliers Yard’ – and so it’s no surprise to find that it’s also home to Jordan Smith, who runs a talent agency called Rebel, with more than 40 content creators on its books.

‘Manchester is a really hot topic,’ says Smith, 31, who moved to Manchester from London after getting disillusioned with the capital during the pandemic lockdowns. ‘A lot of influencers and celebrities I knew lived in Manchester. So for me, the move was an absolute no-brainer. It would satisfy my city needs, but also help my business as well, as it gave me the ability to network, which is critical to my success.’

Property prices were also an attraction: ‘Oh God, yeah, absolutely. You get an apartment for about half the price you would in London. The Cortland is a very premium building, but for a one bed flat you’re looking at £1,800 a month plus bills. And then for the larger deluxe apartments, you’re looking at £3,000 to £5,000,

‘There’s a good positive vibe, too, and it’s got quite a young base, so I found it the perfect place to be in my late twenties and obviously most of my influencers are in their early twenties.’

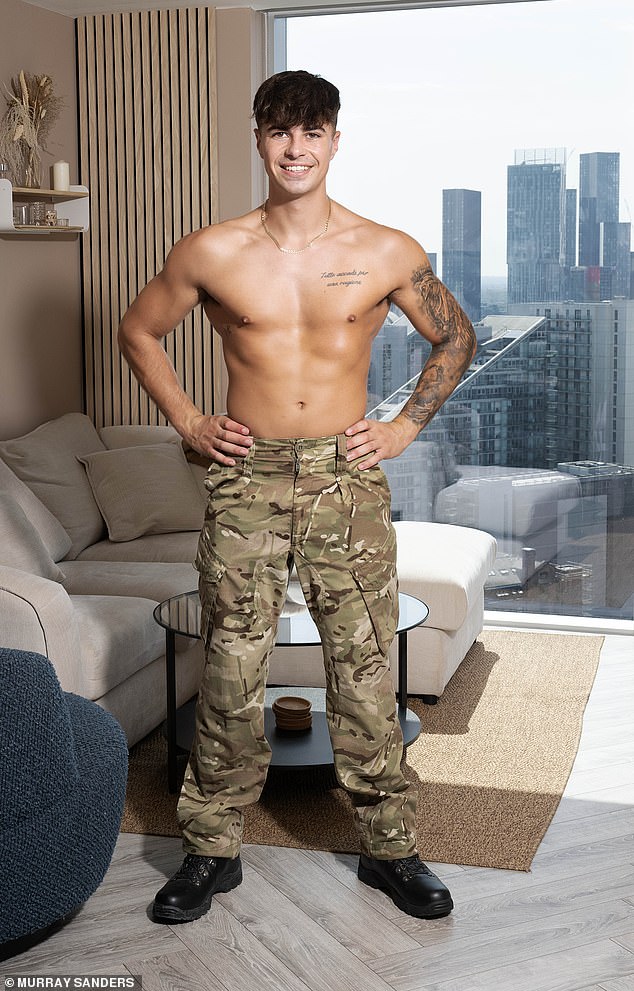

Zak Blackman, who is well on his way to becoming a millionaire through content creation, says he absolutely loves living in Manchester

Thomas Walters, aka Tomo, first made his name at the age of 17 with a YouTube ‘reaction channel’ – but it was after turning himself into a self-taught music producer that he hit the jackpot

One of these is Zak Blackman, 22. He began his career as a content creator on the porn-dominated, subscriber-only site OnlyFans, while still serving in the Royal Navy aboard the aircraft carrier HMS Prince Of Wales.

At the time he was on a salary of around £1,500 a month as a ‘naval airman’ but earned more than double that by posting raunchy images and videos online for people who liked a man in – or, rather out of – uniform.

Perhaps inevitably, word of his extra-curricular activities leaked out and one day in July 2023 he was ordered back from shore leave and summarily dismissed for bringing the Navy into disrepute after refusing to take down his posts because they were earning him ‘so much money’.

And that’s when he really started raking it in. ‘My story made headlines all around the world. And then it just skyrocketed. Just kept going up and up, until it got to about £30k a month or something.’

Naturally, he bought a flash car – a sky-blue Porsche Cayman, a model which costs up to £130,000 new – and, because he had friends in Manchester, moved north.

‘They were doing so well for themselves,’ he says. ‘They lived in a tower like this and I just kind of wanted everything they had, like money, nice cars, nice house, everything.

‘At first I moved into a one-bed that was just under 2k a month and then I decided I wanted an upgrade, so I ended up moving to the top floor into a penthouse. That cost about 37k a year so it was very expensive. And that was just the rent – I had all the bills on top of that.

‘But it was amazing. Some days I’d wake up and be above the clouds. My ears would pop when I took the lift. It was like nothing I’ve ever experienced before. It was the craziest thing ever.’

Richard Eden left his job as an investment banker in 2008 and took over his family’s clothing business, turning it into upmarket men’s fashion brand Private White VC

Dominic Midgley outside the Hacienda apartments, on the site of the famous Hacienda club in Manchester’s city centre

Not as crazy as some of the kinks that make him money from his OnlyFans posts. In addition to his strip shows and the explicit sex tapes he makes with female co-stars, he has cornered the market in sock fetishism.

‘At the minute, I’m doing a lot of feet-based stuff, a lot of sock stuff,’ he says. ‘I never realised there was such a big niche in feet. I’ll go around places in the UK and leave my socks. I then post the location online and they’ll be gone in about 30 seconds.’

He also caters for what he describes as ‘custom requests’, which can be as innocent as a video of him combing his hair in the morning.

Perhaps understandably, given that he’s well on the way to becoming a millionaire – as well as being on track to achieving his ambition of buying a Lamborghini – Blackman absolutely loves Manchester.

‘It’s like the second capital,’ he says. ‘I’d say it’s way better than Birmingham. It’s got taller towers, nicer bars, nicer restaurants. I like everything about it really.’

He adds: ‘I’ve noticed that so many people – content creators in particular – have moved from London to be here. So many people you speak to on the streets these days are not from Manchester. It’s just become the place to be.’

Indeed, Blackman’s become such a convert to the delights of his adopted city that he’s even dropped his previous allegiance to Watford FC in favour of Manchester United.

Two miles southwest of the Cortland, in another towering residential block, lives a very different type of content creator, Thomas Walters, 25, aka Tomo.

He first made his name at the age of 17 with a YouTube ‘reaction channel’ – a sort of one-man Gogglebox about video games – but it was after turning himself into a self-taught music producer that he hit the jackpot.

Last year, he came across an instrumental track by a Ukrainian producer-cum-composer called Frozy that had gone viral. On a whim, at 3 o’clock in the morning and in five minutes flat, he wrote some lyrics, recorded himself singing them and posted the result on TikTok.

What happened next is like something out of a movie. The American pop star Jason Derulo messaged him out of the blue to request his number, followed up with a call and, within days, Tomo was hanging out in LA.

There, he and Derulo collaborated with Frozy on a single called From The Islands, which got over 120 million streams and made Billboard’s Top 50 TikTok chart, as well as its Top 50 dance/electronic chart.

Unlike Blackman, Tomo is a local – Oldham-born and educated in Salford. ‘I feel like Manchester is the number one creative space to be in the UK at the minute,’ he says. ‘London is obviously very, very creative… but to get in with people is very, very hard. In Manchester, I feel like you can meet someone on the street and, within two weeks, you could be doing something completely different.’

Mainstream media is also big up north. The BBC put rocket boosters under this sector in 2011 when it began moving some of its departments from London to Salford’s Media City, a 200-acre TV and tech hub set up on the site of the city’s derelict docks.

Today, BBC Breakfast, BBC Sport, CBBC, and BBC Radio 5 Live are all based in Media City, a relocation drive that has created an estimated 4,600 new jobs.

Manchester’s buoyant economy and the success of its two Premier League football teams are attracting big names in hospitality, too. Soho House will open its first club outside the south of England across five floors of the former Granada Studios later this year. Gordon Ramsay and Richard Caring both launched restaurants in Manchester in 2023. And the hotel sector is flourishing.

Many credit the city’s go-ahead Labour mayor Andy ‘King of the North’ Burnham for creating the conditions for business to prosper. Apart from championing the high-rise revolution, he improved transport links by taking the bus network back into public ownership and last month announced plans for a new underground system for trains and trams.

He has also become something of a style icon thanks to his preference for bomber jackets rather than suits. At least three of them come from a local luxury menswear firm, which is run by James Eden, 42, a former investment banker with RBS in the City of London.

Until the credit crunch hit in 2008, Eden had enjoyed a lucrative but, ultimately, unfulfilling career in the Square Mile and the financial crisis persuaded him to switch careers. As he says: ‘My reality cheque had bounced.’

Fortunately, his decision to apply for voluntary redundancy coincided with the emergence of a business opportunity in the city in which he’d been brought up, in the shape of his family’s clothing manufacturing business.

It had been acquired by his great-great grandfather Jack White, who had started out as a trainee pattern-cutter after returning from the Great War with a Victoria Cross, in the inter-war years.

But, by the time it came to Eden’s attention, it had lost one of its biggest clients, Burberry, and its future looked uncertain.

His inspired solution was to transform it into an upmarket men’s fashion brand in its own right and he didn’t have far to look far for a suitably swashbuckling name for his new venture: Private White VC.

His great grandfather’s medal-winning exploits had been immortalised in a 1987 edition of Victor, the weekly boy’s adventure comic devoted to tales of wartime derring-do.

It revealed how Private White had saved a boatload of men by towing them to safety using a length of copper telephone wire while under fire from German troops.

To this day, Grandpa Jack’s exploits are immortalised in the copper zips and rivets that adorn the company’s garments, while many jackets are lined in the colours of his regimental blanket.

Private White VC’s commitment to time-honoured practices of marking up cloth with chalk and hand-cutting patterns with shears in a factory that dates back to 1853 have attracted a legion of celebrity customers, including former Manchester United great David Beckham, Coldplay’s Chris Martin, and actors Eddie Redmayne, Pierce Brosnan, Henry Cavill and Tom Hardy.

Eden says the company now has a turnover of £10million and is growing at an extremely healthy rate of 25 per cent a year.

And he has seen similar progress in the city at large during the 15 years since he returned to his hometown.

‘We’ve got some phenomenal world-class restaurant bars and hotels now, which we never used to have. So the food scene is incredible. The art scene is incredible. The culture scene is incredible.

‘There’s also an incredible amount of retail, residential development. You’ve got skyscrapers, you’ve got prefab apartments, you’ve got, I think, the biggest student capital population in Europe, and that’s booming and bustling. So there is a real dynamism here.’

Sadly, the Hacienda is not part of this urban revival. A club that played host to the likes of Madonna, The Smiths, Oasis and The Stone Roses during its glory days closed in 1997, brought low by a combination of financial losses, gun crime and drug issues. Today, a residential block stands on the site it once occupied named, perhaps inevitably, Hacienda Apartments.

The second and only other time I saw Tony Wilson was when I sat opposite him at the wedding reception of a mutual friend in Berlin in 2003. A few years later, he contracted liver cancer and died of a heart attack in early 2007 at the age of 57. Poignantly, his coffin was given the catalogue number FAC501.

But Wilson’s dream of a revitalised Manchester did not die with him. The revival he kick-started all those years ago has transformed the city’s fortunes. It’s no longer grim up north. Indeed, it’s rather jolly.