Twenty years ago exactly, in August 2005, Bezalel Smotrich was a 25-year-old settler activist arrested and briefly jailed on suspicion of launching violent disruptions to protest Israel’s historic withdrawal of Jewish settlements from the Gaza Strip.

By 2019, he was the leader of the furthest-right faction in Israel’s Parliament, with a manifesto in hand to annex the West Bank.

Though an ultranationalist figure whose extremist politics and messianic religious ideology are considered outside the Israeli mainstream, Mr. Smotrich is now more than two years into his tenure as the government minister overseeing settlements and the West Bank.

Why We Wrote This

Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich is a second-generation West Bank settler who opposes a Palestinian state, talks of resettling Gaza, and uses his stature in Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition to relentlessly pursue pro-settlement policies. His plan is advancing.

It’s a role in which he’s been methodically pursuing an agenda to officially throttle prospects for a future independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza.

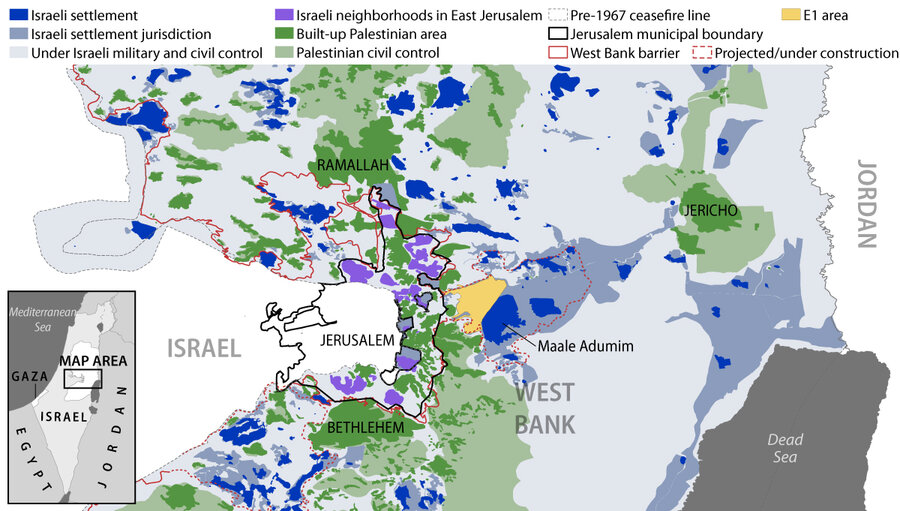

Mr. Smotrich, who is both finance minister and a minister in the defense ministry, celebrated his most recent win on Wednesday when an office he oversees gave final approval for the controversial “E1” settlement project east of Jerusalem. The ambitious building plan would sever the main Palestinian transportation routes linking the West Bank’s north from its south, creating an enormous impediment to a prospective two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“It’s a significant step that practically erases the two-state delusion and consolidates the Jewish people’s hold on the heart of the [biblical] Land of Israel,” Mr. Smotrich said, welcoming news of the plan’s approval. “The Palestinian state is being erased from the table not by slogans but by deeds. Every settlement, every neighborhood, every housing unit is another nail in the coffin of this dangerous idea.”

In from the fringe

Mr. Smotrich, a media-savvy, second-generation West Bank settler and trained lawyer who heads the Religious Zionism party, hit the political jackpot in Israel’s last national election in 2022. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, on trial for corruption and running short of centrist and even right-wing allies, plucked him out of relative political obscurity and paired him with another far-right politician, Itamar Ben-Gvir, in order to secure a coalition government.

Together, Mr. Smotrich and Mr. Ben-Gvir comprise the “messianic wing” of the coalition, with outsize coercive influence over Mr. Netanyahu and government policies. The two consistently oppose proposed ceasefire deals in the war in the Gaza Strip, and speak repeatedly of reoccupation and resettlement of the devastated enclave.

For Mr. Smotrich, cinching the coalition deal was Mr. Netanyahu granting him unprecedented power to oversee Israel’s settlement enterprise and the civil administration in the occupied West Bank.

Within weeks of coming into power, the government announced an ambitious plan to overhaul Israel’s judiciary, a bid that critics labeled a “judicial coup” designed, in part, to protect Mr. Netanyahu from prosecution. It was adopted by Mr. Netanyahu’s ruling Likud party, though it had not been mentioned during its election campaign.

Mr. Smotrich, however, had previously made the overhaul part of his party’s platform, arguing it was a necessary correction to tame what he described as an activist court trying to interfere in politics – specifically in the government’s actions in the West Bank. Over the years, Israel’s Supreme Court had blocked numerous settlement proposals and unauthorized land grabs, as well as government expropriation of Palestinian-owned land.

Though the controversial judicial plan was temporarily halted by a pro-democracy movement that staged the largest sustained mass street protests in Israeli history, Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel followed soon after, plunging the country into crisis and completely consuming the public’s attention.

“Facts on the ground”

It has been in that void, and buoyed by the election of President Donald Trump in the United States, that Mr. Smotrich has been able to double down on his plans in the West Bank. Unlike his predecessors, Mr. Trump has not attempted to police Israeli actions there. That has helped facilitate a spike in settlement construction, including new roads and infrastructure, as well as the expansion of unauthorized settler outposts.

Alongside the “facts on the ground” has been a dramatic rise in settler violence that critics say is not haphazard, but takes place with the tacit approval of the government. The purported goal of the violence is to transfer Palestinian residents out of the West Bank’s so-called Area C, which contains Jewish and Palestinian communities.

“Smotrich is fulfilling his fantasies. [But] these are not only fantasies, but a plan. He knew exactly what he wanted when he was advocating for dismantling the Civil Administration, because he wanted for it to be controlled by the government and not the military,” says Hagit Ofran, who leads the Settlement Watch division of the veteran Israeli organization Peace Now.

In the aftermath of the 1967 Mideast War, when Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan, Israel’s military, in keeping with international laws regarding occupation, became the ruling administrative authority, charged ostensibly with protecting the Palestinian population there.

Israel’s Supreme Court has stipulated that Israeli rule of the West Bank be contingent on it being a temporary occupation overseen by the army, not one managed by civil servants.

Mr. Smotrich, Ms. Ofran says, has replaced all the legal advisers running the Civil Administration with his own people who share his goal of annexing the West Bank.

She cites Mr. Smotrich’s own words recorded and leaked last year, when he told supporters that the changes he was making were indeed intended for that purpose.

Ms. Ofran also notes that Mr. Smotrich boasts of allocating 7 billion Israeli shekels (about $2 billion) to West Bank road construction over the next five years, far more than is planned for construction of intercity roads in Israel. She says it’s part of laying the groundwork to as much as double the West Bank settler population from the current half-million.

“Settlement growth in the last two decades is mainly natural growth, based on those born there. But if you want to attract new people to come, you need infrastructure for that and this is what the government is doing,” says Ms. Ofran.

Settlements are illegal under international law, but Mr. Smotrich sees them as an imperative under his interpretation of religious Zionism, which after 1967 embraced a theology fused with the goal of settling the West Bank, the heart of the biblical Jewish homeland. He grew up in the West Bank, where his parents – his father is a rabbi and his mother a teacher – had moved for ideological reasons.

As a teenager, he studied at Mercaz Harav, the national religious community’s flagship yeshiva in Jerusalem. He was raised at home and in his studies on the idea that Jewish settlement of the biblical Land of Israel will lead to the coming of the Messiah.

In his 2017 manifesto, which he called “Israel’s Decisive Plan,” he wrote: “I believe in the Torah which foretold the exile and promised redemption. I believe in the words of the Prophets who witnessed the destruction, and no less in the renewed building that has taken shape before our eyes. I believe that the State of Israel is the beginning of our unfolding redemption, the fulfillment of the prophecies of the Torah and the visions of the Prophets.”

Mr. Smotrich outlined the options for Palestinians who live there as either to emigrate, declare allegiance to Israel and agree to be loyal subjects without voting rights, or risk the consequences of fighting.

E1 Project

The E1 plan has been around since the late 1990s but had been shelved, in large part because of U.S. opposition. The project would see 3,400 housing units built between Jerusalem and the large settlement of Maale Adumim.

“The idea of establishing settlements there or anywhere from the beginning was not about regular planning rationale but mainly to create a matrix of control of the West Bank,” says Alon Cohen-Lifshitz, an architect and urban planner at Bimkom, an independent Israeli organization focused on Palestinian land rights.

As part of the plan, he says, roads Palestinians now use there would be banned to them, replaced by a complex and forbidding system of tunnels.

In the past, Israeli officials have defended the project, saying contiguous settlements were key to the security of Maale Adumim, which had become a main commuting suburb of Jerusalem.

Powerful, but unpopular

Though Mr. Smotrich scores points with the national religious camp for bolstering settlements, he’s otherwise so unpopular even within that community that polls indicate he could lose his seat in the next election.

That’s because, says Yair Ettinger, a commentator on religion and state issues for public broadcaster Kan News, there’s frustration with his management as a security Cabinet member of the Gaza War – specifically his seeming disregard for hostages’ lives.

Also, Mr. Ettinger, author of “Frayed: The Disputes Unraveling Religious Zionists,” says, Mr. Smotrich’s support of an exemption of ultra-Orthodox Jews from compulsory military service is very unpopular with a religious nationalist community that has sustained many casualties in the war.

The public sees, he says, that “Hamas is still in Gaza, the [remaining] hostages are still not home, and many Israelis are not convinced he knows what he is doing.”