Perched just north of the Florida state line, Folkston, Georgia, has long been known as a gateway to the alligator-guarded Okefenokee Swamp. But it may soon be known for something else.

This rural town of 5,000 is fast becoming one of the United States’ most significant deportation turnstiles – home to a massive, refurbished, and privately run detention center for immigrants who have been rounded up by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

But the detainees here aren’t being arrested at the border. They’re being picked up in the U.S. interior.

Why We Wrote This

The messy business of mass deportation has come to Folkston, Georgia, where preparations have begun at a newly expanded detention center. Some worry that the effort represents a dangerous turn away from American values.

Already, the number of immigrants in custody in Georgia is second only to Louisiana among nonborder states. The expanded center in Folkston, which combines an existing detention facility with a separate, shuttered prison nearby, will create room for another 3,000 detainees, roughly doubling the number already in custody for immigration issues in Georgia.

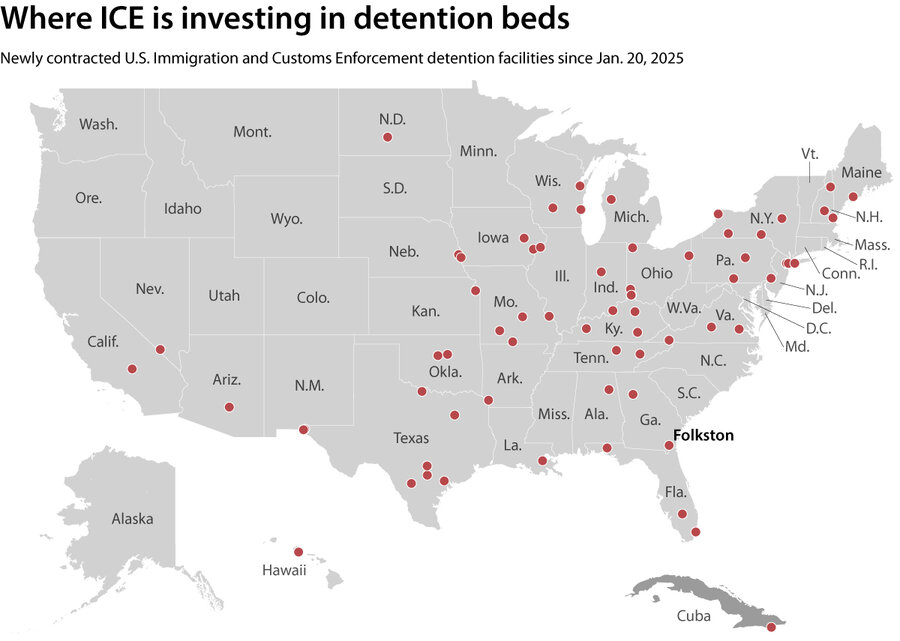

It’s one of 71 new ICE-contracted detention facilities – spanning from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Cedar Rapids, Iowa – that have come online since January to help execute the Trump administration’s accelerated arrests and deportations. Until now, this medium-security complex has held a relatively small number of immigrants arrested for ICE-related matters.

Economically, the nearly $50 million paid by the Department of Homeland Security to expand and repurpose the D. Ray James Correctional Facility here in Folkston represents a significant boost for a town so poor that it has struggled to raise funds to build a state-mandated water treatment facility.

As a result, Folkston’s complex on the edge of town – consisting of its ICE detention center, which opened in 2017, and a long-running private prison that emptied during the pandemic – is buzzing with new life. Brand-new white transport vans are lined up beneath razor wire. Faded signs are being replaced with fresh, crisp ones.

But the town also serves as a poignant example of how communities that host these new federal detention centers are, like the nation itself, wrestling with mixed feelings. Optimism that locals express about new jobs and dropping crime numbers is combined with wariness about the Trump administration’s raids and treatment of those it arrests, some of whom are longtime community members.

Folkston’s Mayor Lee Gowen, who also works as a trailer salesman, calls the new detention center “a blessing.” But, he adds, the positive impacts of new detention facilities may be shorter term than many communities expect, particularly concerning economics. Kristi Noem, Secretary of Homeland Security, pointed out last week that longer-term contracts for facilities shouldn’t be necessary if the administration successfully meets its deportation goals.

“In four years, if and when you get an administration change, who knows what will happen?” says Mayor Gowen. “We’re glad the facility is open for however long it is. We don’t get into the politics of it. We do our own thing.”

A big expansion in a small town

Mr. Gowen, like others here and across the country, notes the inherent tension in a nation founded and expanded by immigrants now conducting a mass immigrant deportation effort. Critics argue that it represents a dangerous departure from American values.

Folkston native Jobe Hannan, for one, spent his entire career working in the timber industry. But when an old mill where he worked burned down, it was never rebuilt – a sign of the region’s flagging fortunes.

Still, for him, no economic boon is worth the damage to America’s values that a detention program targeting specific ethnic groups – in this case, people from Latin America – might cause.

“We’re doing this massive thing that we think only hurts one [group of people],” says Mr. Hannan. “But everybody is going to suffer.”

Many voters were unhappy about the surge in illegal immigration in the years leading up to the 2024 election, and were looking for solutions, says Mara Ostfeld, a public policy professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. But “a lot of people weren’t envisioning masked agents pulling people off the street. And now we can’t find them, and we don’t know what happened to them,” she says.

But the economic argument is a compelling one for small towns and businesses that require additional funding.

A congressional infusion of $45 billion to expand an already sprawling immigrant detention system nationwide, provided as part of the Trump administration’s “Big Beautiful Bill,” means windfalls for places like Folkston. It is also a moneymaker for private prison companies like GEO, which operates the Folkston center.

That congressional funding for the nation’s detention centers is enough to roughly double the current capacity, up to 100,000 beds. The average stay for detainees is just over two months as cases are adjudicated.

“We are now on the verge of a historic infusion of money” into detention centers, says César García Hernández, author of “Welcome the Wretched,” and a law professor at the Ohio State University in Columbus. That big a boost seems likely to be transformative, one way or another.

New ICE facilities nationwide

The facilities, which are opening or reopening across the country, come in various forms. In California, Georgia, Kansas, and Michigan, ICE is reopening shuttered prisons, converting them into ICE detention centers. Other outposts are simply county jails where ICE rents beds. The agency has expanded existing prison contracts in Mississippi, Nevada, Ohio, and Oklahoma. Others, like the quickly erected and state-run “Alligator Alcatraz” in southern Florida, resemble networks of large canvas tents. And then there are stand-alone complexes like Folkston.

All restrict movement “like typical jail or prison experiences in the United States,” says Professor Hernández.

The Trump administration argues that the push to expand detention space is necessary to address “the urgent operational need created by [the Biden administration’s] open-border policies,” according to an ICE statement responding to Monitor questions.

It is also meant to act as a deterrent. Highlighting the prospect of detention in places far from lawyers and family, some with ominous names, is part of the administration’s plan to discourage illegal immigration, DHS Secretary Kristi Noem said last week.

“There definitely is a message that it sends,” Secretary Noem said. “President Trump wants people to know if you are a violent criminal and you’re in this country illegally, there will be consequences.”

In addition to officials in Georgia, Louisiana officials have begun talks with the Trump administration to house detainees at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, called “Angola prison” due to its location in Angola, Louisiana. It is the largest maximum-security prison in the U.S. A new facility located in Fort Bliss, Texas, is scheduled to open on Aug. 17, with an initial capacity for 1,000 people, and is expected to expand to house 5,000 eventually.

But even as the administration says it is deliberately trying to sow fear, ICE also says it is providing humane treatment of detainees, including medical care, mental health screenings within 12 hours of arrival, and regular audits to ensure that standards are met. Detainees have opportunities to communicate with family and lawyers, according to the ICE website.

Still, says Professor Hernández, the remote locations of many detention centers mean that detainees – including permanent residents, asylum-seekers, and even U.S. citizens – are often hard, if not impossible, for families and friends to locate. That means they may not have any help making last-ditch appeals to remain in the U.S.

Last week, a Chinese national died by suicide inside a large detention center in Pennsylvania. Fourteen people have died in ICE custody since Oct. 27, 2024.

The same issues are true here.

Unsanitary and dangerous conditions have cropped up at the existing Folkston ICE facility in the past, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman. And last year, a 57-year-old Indian national, Jaspal Singh, spent nine months at the facility and died after delayed medical treatment, the agency found in a review of Mr. Singh’s death.

Immigration politics

For its part, the Trump administration seems aware of the political pitfalls associated with the prolonged detention of those without criminal convictions. As of late July, 71% of those recently detained under the Trump administration’s sweeps have no criminal convictions – or any criminal records, according to the nonpartisan Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

The U.S. has also, in the past, processed most unauthorized migrant populations without detention at all, using alternative approaches such as releasing migrants with a surety bond or payment, or registering them for community-based supervision.

Consequently, there are signs that the administration’s efforts to move quickly with arrests and jail time to deliver on its immigration promises could become a liability. A recent UMass-Amherst poll shows that President Trump’s approval rating on immigration has dropped from 50% four months ago to 41%.

Whether that drop reflects changing sentiments here in South Georgia is hard to gauge.

Reliant on massive pine plantations, where pine trees are harvested for timber production, and a nearby submarine base, Folkston is a conservative place. Surrounding Charlton County cast nearly 80% of its votes for Mr. Trump in 2024, with many here blaming unchecked immigration and unfair trade deals for their economic struggles. Folkston’s high school gymnasium has broken windows, and the football field is known as “The Swamp.”

“A lot of people around here are pretty conservative [on immigration] and gung-ho about, ‘Yeah, let’s round ’em up, kick ’em out,’” says Patrick Morgan, owner of Black Cypress Sound, a music store. Mr. Morgan says he has friends who had been laid off from the prison but have recently been rehired to work at the new ICE expansion.

But his own feelings about immigration and the Trump administration’s raids and mass arrests for deportations are more complex.

For one, he doesn’t trust the government on principle, he says. There are also fairness and economic issues at play, and it doesn’t hurt to have more jobs, such as those that the new prison will provide. However, he admits to having some sympathy for those who come here seeking a better life.

“I mean, we’re a country of immigrants after all,” he says. “And if you think about it, there’s always a reason why they are here. My point is, if you’re going to come here, you’ve got to do it the right way.”