Her story is horribly familiar. A hard-working blonde nurse found guilty of killing seven of her patients, including at least three babies, and told she will spend the rest of her life behind bars.

Circumstantial evidence, including disturbing handwritten notes, apparent poisonings and a damning shift pattern which showed she was on duty at the time of all of the deaths.

But though the name Lucy Letby springs straight to mind, this is actually the saga of Lucia de Berk, a paediatric nurse from the Netherlands who, like Letby, was labelled an ‘angel of death’ (as well as the worst serial killer in the history of her country).

Unlike 35-year-old Letby – who was found guilty of murder at the end of her first trial two years ago this week – Lucia, however, is now free.

She served nearly seven years in prison before her conviction was overturned in 2010 after a group of experts raised serious doubts about how her case had been prosecuted and debunked a statistician’s claim that there was only a one-in-342million chance that the deaths on her shifts were an accident rather than murder.

Letby’s supporters are now drawing parallels between her case and that of the ‘Dutch Lucy Letby’ in the belief it may hold the key to overturning her conviction.

Among them is British academic Professor Richard Gill, a leading expert on statistics in medical murder cases, who has previously worked with police and was part of the team who helped free Lucia.

Speaking exclusively to the Daily Mail, he said he is convinced mistakes made in the earlier case, including bad statistics, tunnel vision and inaccurate assumptions, also featured in Letby’s conviction.

Letby’s supporters are now drawing parallels between her case and that of the ‘Dutch Lucy Letby’ in the belief it may hold the key to overturning her conviction

When reports of a spike in deaths at the Countess of Chester Hospital in Cheshire first reached him in 2017, Professor Gill says his heart sank. ‘Then when I heard they’d arrested a nurse, I thought, ‘Oh God, here we go again’.’

The prosecution cases against both women, he argues, were built on the lure of the ‘impossible coincidence’, leading to the assumption of murder and then a search for suspicious deaths to lend weight to that theory. Such a fallacy, he argues, ‘sometimes falsely joins the dots in the evidence’.

As for Lucia, a source this week said she is well aware of Letby’s case, and has been watching from afar, ‘anguished’ at the possibility history might be repeating itself.

Letby’s case, the source says, ‘brings it all back to her’.

More, later, of how Cambridge-educated Gill, Professor Emeritus of mathematical statistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, helped pick apart Lucia’s flawed conviction.

For the resurfacing of her case coincides with what many now regard as a shift in public sentiment about the former neonatal nurse’s eight-month trial.

This week’s BBC Panorama programme – Lucy Letby: Who To Believe? – highlighted the growing number of experts questioning the methods used to convict her.

An ITV documentary – Lucy Letby: Beyond Reasonable Doubt? – also questions the science and statistics around her case.

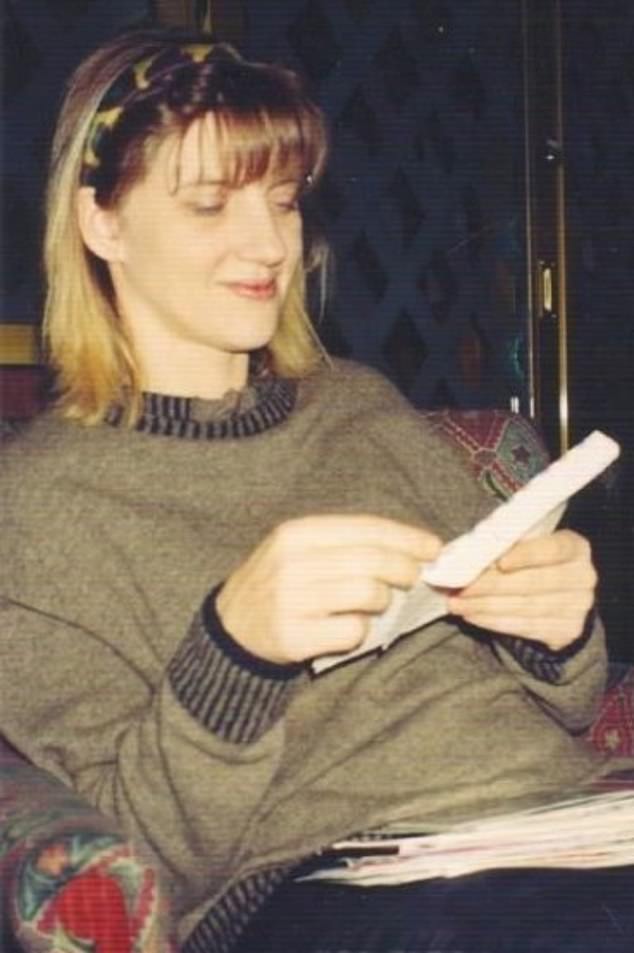

Lucia de Berk served nearly seven years in prison before her conviction was overturned in 2010 after a group of experts raised serious doubts about how her case had been prosecuted

Now aged 63, Lucia is a married grandmother who lives in a quiet corner of Holland and devotes herself to her family and her garden. ‘She prefers not to speak of her ordeal or the years she spent in prison because it forces her to relive the pain of the past. She was heavily traumatised,’ a source told the Mail.

But the diaries Lucia kept throughout her ordeal, and which were later published in the Netherlands, offer a dramatic insight into her state of mind at the time of her trial – and the horror she faced when she realised that her proclamations of innocence were falling on deaf ears.

‘How in God’s name have they got this in their head?’ she wrote. ‘How can they think such a thing about me? How dare they accuse someone of such terrible deeds without being sure? Without any evidence? What kind of country is this where such things are possible? And in a democracy! In the 21st century!’

In a rare interview she gave to a Dutch newspaper after her release from jail 15 years ago, she said: ‘I want people to know my story. I want to warn them, especially nurses: what happened to me could happen to you.’

Lucy Letby was an 11-year-old pupil at Aylestone School in Hereford when 14 police officers stormed into Lucia’s home in December 2001 and arrested her.

Lucia, then 39, later said that ‘nothing was explained to me, just ‘You are suspected for murder’,’ adding that ‘I just couldn’t grasp it. It was too much’.

A five-month-old baby had died unexpectedly while Lucia was on duty at Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague.

In what reads like a foreshadowing of Letby’s case, a colleague then claimed Lucia had been present at a suspiciously high number of deaths and resuscitations.

Hospital staff called the police and when investigators examined Lucia’s shifts they found ten allegedly suspicious incidents. Ten more were apparently uncovered at three other hospitals where she worked between 1997 and 2001.

She was charged with killing 13 babies, toddlers and some elderly patients and attempting to kill five others by injecting them with tranquillisers, painkillers and potassium. Being locked up in a cell – ‘like a monkey in a cage’ – recalled Lucia, was ‘too crazy for words. It’s awful. You try to tell people you’re innocent but it’s like hitting a wall. Nobody believes you.’ She would later recall the way the female prosecutor glared at her across the court room: ‘The hate in her eyes was unbelievable.’

The crux of the evidence against her – as with Letby – was that it was too much of a coincidence that all the unexpected deaths and suspicious incidents fell within the shifts of only one nurse.

At her trial, which began in 2002, a criminologist who had studied statistics as an undergraduate incorrectly put the odds of Lucia’s presence at the deaths being just a coincidence at one-in-342million, a claim so compelling it blotted out any alternative explanation and led the police and the Dutch courts to conclude that any other verdict than guilty was unthinkable.

Piled on to that damning statistic was the ‘smoking gun’ evidence – traces of toxins found in the exhumed bodies of two children (later shown to have been caused by treatments they’d received).

There was also a 1997 diary entry on the night one of her patients died in which she wrote: ‘I gave in to my compulsion … I don’t even know why I am doing it … I hope I’m helping people by doing this.’ She was in fact referring to her habit of reading tarot cards for dying patients. Nearly two decades later, fragments of notes written by Letby would also be used against her, with phrases extracted for the jury such as ‘I am evil, I did this’ and ‘I killed them on purpose because I’m not good enough to care for them’.

Letby claimed they were not a confession but a reflection of her mental turmoil, written on the advice of counsellors to release the stress of being investigated.

In Lucia’s case, a Stephen King novel and other crime books were said to be yet further proof by the prosecution that she was ‘obsessed by death’. She later wrote: ‘The only thing that mattered was that hospital management and the public prosecutions service were proven right. And if that meant a little manipulation here and there, well so be it. The fact that none of the forensic investigations revealed an unnatural cause of death was an unfortunate anomaly. If they shouted loud enough that I was a deranged murderer and made the statistics work in their favour then no one would care about the evidence.’

In March 2003 she was convicted of four of the murders – three babies and an elderly woman – and three murder attempts of two other babies and a pensioner.

In her book, Lucia revisited the moment she heard the guilty verdicts: ‘I can’t believe what I’m hearing; the world is spinning before my eyes and for a moment it threatens to go black. I feel my body go limp.’ When she appealed a year later, the court not only upheld her conviction but convicted her of three additional murders. In addition to her life sentence, she was ordered to undergo psychiatric treatment despite the fact that psychiatrists had found no evidence of mental illness.

When reports of a spike in deaths at the Countess of Chester Hospital in Cheshire first reached him in 2017, Professor Gill, a leading expert on statistics in medical murder cases, says his heart sank. ‘Then when I heard they’d arrested a nurse, I thought, “Oh God, here we go again”‘

A second appeal failed in 2006 and four days later Lucia suffered a stroke which left her right arm paralysed.

That was the year that Professor Gill started looking into the statistics behind Lucia’s conviction. He joined forces with philosopher of science Ton Derksen who wrote a book about the case. Along with Derksen’s sister, geriatrician Metta de Noo, they established that flawed statistics had driven Lucia’s conviction.

The ‘one-in-342million’ figure had been based on ten unexpected deaths alleged to have occurred in 2000 and 2001 during her shifts as well as the number of Lucia’s shifts compared to all shifts.

But after re-examining medical notes and rosters, Derksen and Noo found that there were actually 20 suspicious incidents and that only six had occurred on Lucia’s shifts, altering the chance that it was an accident – and not a murder – firstly into something like one in 50. Taking into account other factors, Gill found that the probability of so many deaths occurring by chance may have been as high as one in 25.

As Professor Gill puts it: ‘The string of deaths which had occurred when Lucia was on duty might just as well have been entirely due to coincidence.’

Other key data had also been ignored by the prosecution.

During the three years before Lucia worked at the hospital there were seven deaths in her ward. During the three years she worked at the hospital there were six. According to Gill, this was another strong indication that ‘there was not a serial killer at large’.

He adds: ‘In a normal murder case, you actually have a body which has clearly been murdered. When there’s only a suspicious cluster of deaths, investigators may assume a murderer is at work and selectively focus on evidence that supports that assumption.’

Convinced of her guilt, police and hospital managers put together a dossier in which it appeared that every death which occurred on Lucia’s shift was suspicious even though there was no direct evidence against her. Deaths which had been recorded as natural were reclassified as unnatural when hospital authorities discovered de Berk had been on duty.

Lucia’s conviction was overturned in 2010. An appeal judge stated that not only was there a lack of evidence, but that most likely ‘nobody was killed at all’.

Lucia later received a letter of apology from the Dutch minister of justice and an undisclosed amount of compensation.

Letby is serving 15 whole-life terms at HMP Bronzefield for the murder of seven babies and the attempted murder of a further seven. She has already lost two appeal attempts. In May last year, the Court of Appeal dismissed her case on all grounds and rejected her argument that the expert prosecution evidence was flawed.

Her fate now sits with the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), which has the power to refer convictions for appeal. But their work, which involves rereading everything presented at her eight-month trial, could take years.

Among those fighting her case is a 14-strong team of eminent neonatologists and paediatricians from around the world who claim no scientific proof exists that she ever injected air into babies’ bloodstreams or injected them with insulin, as claimed.

The Royal Society of Statistics (RSS) has also expressed serious concerns about the shift pattern data which was presented as evidence of her presence during infant deaths and collapses.

Professor Gill points to other suspicious deaths uncovered at the Countess of Chester at which Letby was not present, making a total of around 50 unexplained deaths or resuscitations. ‘When we now look at all allegedly suspicious cases, we find that less than half of them are during Lucy’s shifts. That is very different from Lucy being present in all 24 suspicious cases.’

In 2022 he co-authored an RSS report – Healthcare Serial Killer Or Coincidence? – which detailed statistical bias in past medical murder trials. One of their recommendations was that investigators should not be ‘blinded’ by having pathologists classify deaths as suspicious or not without knowing who was in attendance at the time.

After her release, Lucia gave talks to law students in the Netherlands. She said at the time that while she wanted to share her story, she was ‘more distrustful’ of people and that if a baby so much as coughed near her, she would get away as fast as she could.

But she added: ‘I can spend the rest of my life being angry or I can draw a line under it. I’m free. I don’t want the rage to keep me imprisoned.’

Her book, Lucia de B, was made into a film, Accused, which was short-listed in 2014 for an Oscar for best foreign language film.

There are growing numbers, of course, already hoping that one day such a film will be made about Letby. While her supporters await a decision from the CCRC, three senior managers from the Countess of Chester Hospital are on bail after being arrested on suspicion of gross negligence manslaughter.

Many remain convinced of her guilt, including those whose babies died at the Countess of Chester Hospital. A public inquiry into the case is ongoing, with its final report expected later this year. The CPS is also reviewing additional evidence which could lead to further charges against her.

Whatever the future holds, there is little doubt that the Lucy Letby story is far from over. And that few will be watching the case more closely than Lucia de Berk.