There’s something eerily familiar about the model in the latest Guess fashion campaign. Her smile and wide cheekbones are a little like those of the American supermodel Kate Upton. Her hazel, feline eyes meanwhile remind me of the Dutch supermodel Doutzen Kroes.

A glance at her body – long legs, a cantilevered chest, skin the colour of a biscotti biscuit – and it could easily be that of Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bundchen.

But look a little closer and all is not as it seems. A small, barely legible stamp warns us that this is not a real woman at all. Instead she is an AI-generated supermodel, a complete fabrication whose genetic make-up is composed of computer codes and automated learning.

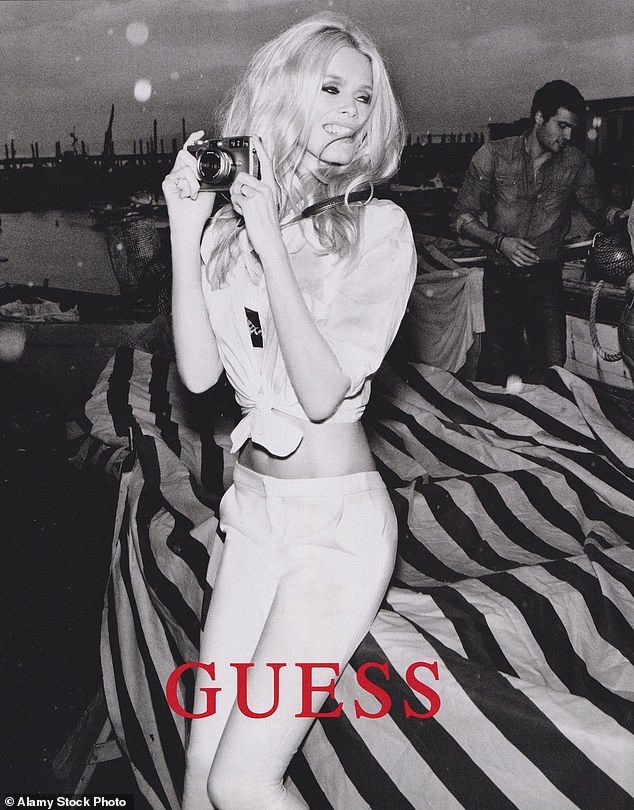

This is the first time that Guess, a US fashion house famous for launching the careers of some of the world’s most famous models – Claudia Schiffer, Gigi Hadid and Laetitia Casta to name but a few – has used AI-generated models in its ads. It’s also believed to be the first time Vogue magazine, which features the advert in its August issue, has allowed computer-generated models in its pages.

But Guess is not the first fashion brand to use AI. H&M and Mango have been experimenting with AI models for some time now, while there have been virtual influencers, such as Marks & Spencer’s Mira, selling products and amassing huge followers for years.

A decade or so ago, artificial intelligence seemed like something from a sci-fi movie. But today, it’s a different tale as new, sophisticated computer learning has been able to replace journalists in newsrooms, extras in films and now models on photoshoots.

As the former editor of Elle magazine, it is easy to see the initial appeal of replacing models with AI, since the business of modelling has always been fraught.

Firstly, from a simple supply and demand perspective, there are never enough of the models you want for the ‘moment’ you want. High fashion is as much trend-led by the models as the clothes. If one season the vogue is for angular, Slavic-looking models, then everyone will be after the same girls. AI solves that problem immediately, allowing anyone to create the model of their editorial dreams.

A Guess advertisement from 2012 featuring Claudia Schiffer.

When I was editing Cosmopolitan, from 2015 to 2019 (before I moved to Elle), we desperately wanted to use models with larger, more realistic body types. The problem was that very few agencies had models over a size 12. Instead we were routinely sent ‘curve’ models with teeny tiny bodies and bigger chests.

In theory, AI would have allowed us to side-step that problem, for almost no cost. (In the end we often resorted to using ‘real’ women to fill the void, which looking back I still believe was the better solution.)

Then, of course, there’s the discrepancy between the model you think you’re booking and the model you get. At all the magazines I edited over my career – Women’s Health, Cosmo and Elle – it was not unusual for models to turn up who were far shorter than expected, with bad skin or hair that had been hacked short for a shoot with another magazine.

At Women’s Health we saw models who clearly had unhealthy exercise addictions; while at Elle and Cosmo we saw so many fragile young women, who were so thin and scared-looking, that it simply did not feel ethically right to book them. (I was very fortunate to work with wonderful fashion directors who were not beyond raising concerns with the model agents.)

AI solves all of this.

And then there’s the cost. The fashion world, not to mention magazines, are currently under incredible pressure to balance the books. Fashion shoots for ad campaigns can costs hundreds of thousands of pounds when you factor in locations as well as the entire creative team – photographer, make-up artist, hair stylists, a phalanx of assistants as well as the hefty travel and accommodation costs. As if by magic, AI makes all of that financial pain go away.

Finally, let’s not forget the safeguarding issue which has been one of the modelling industry’s biggest concerns for many years now. Throwing young beautiful women into an unchaperoned world where money and power abound has had terrible consequences over the decades with several well-documented cases of sexual abuse and mistreatment.

Who can forget the horrific allegations against Elite Model Management boss, Gerald Marie, who was said to have sexually assaulted dozens of young models? He has denied the claims and French prosecutors closed an investigation into the allegations because of the statute of limitations.

One of the adverts created by AI for Guess, the US fashion house that has launched the careers of some of the world’s most famous models

But by replacing models, AI has instantly solved some of the industry’s murkier issues.

So far so good – except I firmly believe there will be a cost if fashion engages too deeply with AI, and that cost is as much existential as it is cultural.

Because the business of fashion, to my mind at least, is not simply about aspiration and selling clothes. Fashion also shapes culture. Get rid of models and you also take out the entire creative system behind them: make-up artists, photographers, stylists, assistants.

Overnight you decimate an entire industry whose work has genuine cultural importance. Fashion sparks ideas and ignites debates. It is an industry that thousands of young, creative people bend towards. Something as seemingly simple as relying on AI to sort out your models pulls at a thread that could potentially unravel an entire fashion industry.

What’s more, a model brings so much more to their job.

In the 1990s, the supermodels were as famous for how they looked on the catwalk as they were for the lives they led off it.

When you hired Cindy Crawford, you were not only buying Crawford’s face and body, you were buying into her All-American persona. You wanted the story of Cindy Crawford as much as you wanted the mole above her lips or her famous 34-25-36 ‘vital’ statistics.

Although AI-generated ‘Mia Zelu’ does state she is a ‘digital storyteller and AI-influencer’ on her Instagram biography, algorithms mean most of her followers are likely to be presented with her image without any further context

When you booked Kate Moss, you were aligning yourself with the rock ’n’ roll image she led outside the world of modelling as much as you were the role she played in front of the camera. Storytelling therefore is as much a part of the model experience – who they are and how they live – as it is the way they look. Something which AI can never successfully compete with.

But perhaps the biggest issue with AI models is this: what happens when a computer gets to decide what’s beautiful?

Because whether we care to admit it or not, models sell aesthetic ideals. Growing up, it wasn’t my parents or friends who had the biggest effect on me. It was fashion – Calvin Klein adverts, Kate Moss, the supermodels, Claudia Schiffer staring back at me from a giant billboard as ‘the Guess girl’.

But if the ‘Guess girl’ now staring back at you is wholly composed by AI, what sort of impossible beauty standard does that set for the millions of young impressionable women who see it? (Interestingly the law has not yet fully caught up with AI and labelling models as computer generated is not yet compulsory.)

A startling example of this is the influencer, Mia Zelu, who caught attention and captured hearts (including that of a world famous cricketer) at this year’s Wimbledon despite the fact she doesn’t actually exist but is AI-generated.

With her bouncy blonde hair, big eyes and long, caramel limbs, it was hard not to be captivated by her exaggerated ‘girl next door’ beauty as she was pictured around the tennis tournament asking questions of her 168,000 followers like: Which Wimbledon match was your fave? Although Zelu does state she is a ‘digital storyteller and AI-influencer’ on her Instagram biography, most people will never see this, since Instagram’s algorithms mean most of her followers will likely be presented with her image without any further context. And, in this case, context really is everything.

Back in 2016, I remember being told about an AI influencer and model called Lil Miquela, who was the creation of the now defunct LA ‘storytelling’ company Brud. I was editing Cosmo at the time and laughed her off at first, since she looked almost like a Manga cartoon.

No one will fall for that, I told a colleague. And yet Lil ‘modelled’ for Prada, Adidas and Calvin Klein as well as many others. The difference however was that most people were in on the fact that Lil was AI-generated.

In truth, that was part of her appeal. Fashion has always loved a novelty, boundary-pushing moment and Lil, titled ‘the world’s first digital supermodel’ captured that moment perfectly. I don’t think anyone I know thought she posed any real threat to the future of fashion.

But models and influencers like Mia Zelu and the new Guess girl? I would have no idea, so sophisticated has AI become in the past ten years.

And yet, I hear you ask, how different is AI to the photoshopping magazines have liberally used for decades – smoothing out skin texture, eradicating lines and spots and in some cases (which UK GQ was guilty of with Kate Winslet, who was very cross at her image being digitally altered) elongating limbs? What about the filters so many people use on social media to scale down noses, round out eyes and chisel jaws?

I regularly see peers whose faces look almost AI-generated due to the overuse of phone filters. Their eyes sparkle, they have unfathomably smooth skin, in short they look as far removed from the person they are as Barbie dolls look from the average woman.

When you consider all of this, then AI doesn’t seem that big a stretch from what we already willingly do to our own image.

But here’s the major difference: filters and photoshopping (which incidentally, the fashion industry has been forced to clamp down on over the years due to legislation and activism) rely on genuine humans to begin with.

That means they are starting from a place of true diversity, since everyone looks different. Photoshopping and filters won’t completely obliterate someone’s skin colour or body shape.

AI is different. That’s because of the way AI is trained. Its underlying algorithms look for patterns; they often produce answers, behaviours or, in this case, aesthetics which are the same, given that it is working from data sets based on historical trends.

In the world of modelling those trends have, generally speaking, always bent towards slim, Caucasian women. It’s not surprising then, that a model like the new Guess girl looks like an amalgam of every supermodel from the past five decades – Patti Hansen, Christie Brinkley, Candice Swanepoel and Kate Upton. That’s simply how AI works.

Which is devastating for a world that has fought for a far broader representation within the modelling industry, whether that’s skin colour or body shape.

Take the body-positivity movement, which has campaigned hard to make curve models a fully recognised part of the fashion scene. Because they are so new, however, AI is not necessarily going to create a plus-size model for you, unless very specifically asked.

The result: a mass, blanding out of certain beauty types.

I have no doubt AI is going to come for us all – writers, directors, shop assistants, even labourers in due course. Modelling is just an early casualty.

What’s more, creating a culture where everything feels sort of the same – whether that’s films or models or books – will mean we human beings will all ultimately disengage.

No one will watch the films and no one will buy the clothes – which is something every fashion company weighing up AI should be thinking about right now.