Addiction was the glue that held Elvis Presley and his manager ‘Colonel’ Tom Parker together during the last few years of the singer’s life.

Twenty years of lonely fame and wild extravagance had meant that by 1977 Elvis was struggling to make ends meet. To pay for his entourage and the compliant doctors who fed him the drugs on which he was hooked, he just had to keep touring.

You might think a sensible, caring manager would have committed his client to a hospital to dry out. But the ‘Colonel’ had an addiction problem, too. When he wasn’t on tour with ‘my boy’, as he would refer to Elvis, he would go on gambling binges at the roulette wheel in Las Vegas.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars slipped through his fingers. Elvis had to keep working to pay for his manager’s gambling losses, as well as his own profligacy.

During his 21-year career, Elvis earned millions, of which, by 1977, the Colonel was taking 50 per cent for himself. Then there were the Colonel’s side-deals.

Elvis didn’t write songs, but to get him to record one the writer would be asked to give up a percentage of his royalty. Thus, as well as his own royalty as a singer, Elvis’s music companies got a third of Heartbreak Hotel and hundreds of other songs, with the Colonel always getting a portion of Elvis’s slice.

Only later in Elvis’s career did songwriters begin to dig their heels in. He wanted to record I Will Always Love You, but writer and singer Dolly Parton wouldn’t let him. She knew the value of her song.

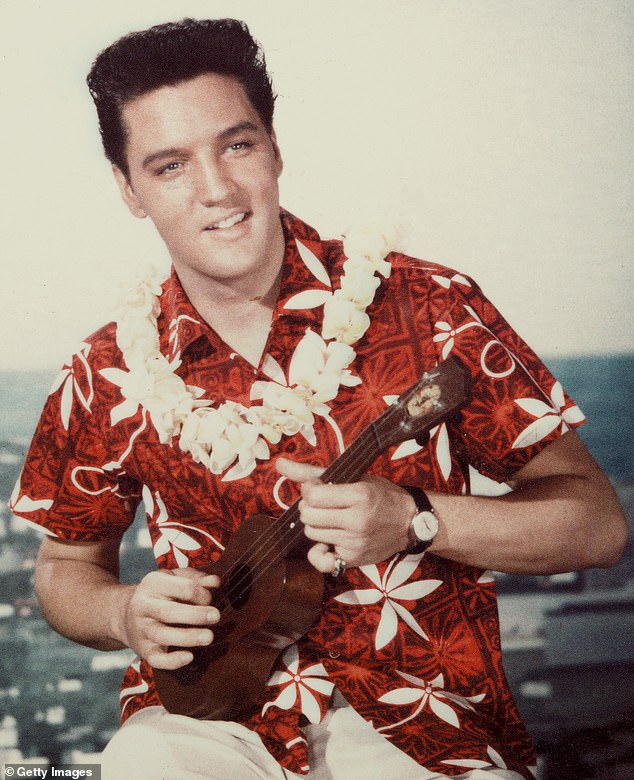

Elvis Presley in a still from 1961 film Blue Hawaii, in which he starred as soldier turned tour guide Chad Gates

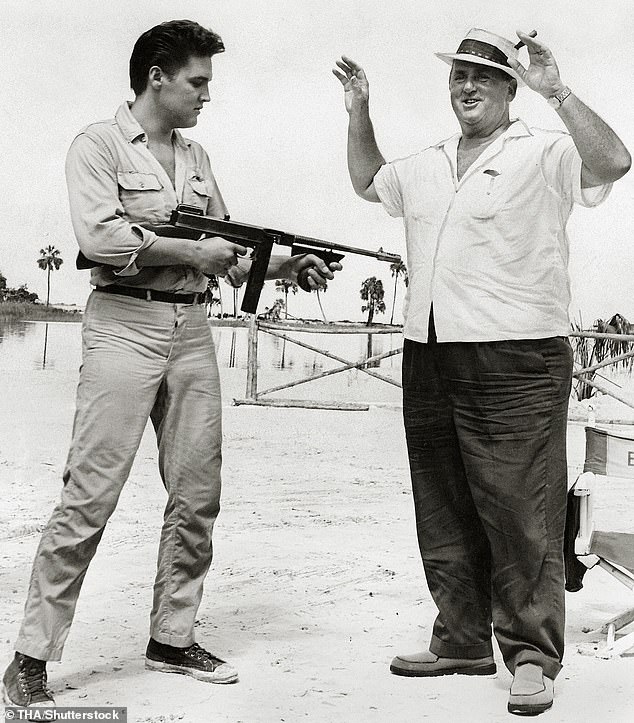

Elvis and Colonel Tom Parker on the set of Follow That Dream in 1962 – one of the 30-odd movies Elvis starred in

Then there were those 30-odd movies in which Elvis appeared. Although the Colonel had no role in any of the films’ productions, his side-deals gave him an office and a further payment in all of them.

He was a shrewd man, all right, but who exactly was ‘Colonel’ Tom Parker?

Well, he wasn’t a colonel for a start. That honorary soubriquet had been bestowed on him by governors of two states while he was working as a promoter. He liked it. It made him feel important.

Neither was he an American. He was, in fact, Dutch. Born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk in Holland in 1909, he’d entered America as a stowaway in the 1920s, where he soon adopted the identity Tom Parker from Huntington, West Virginia.

A short career in the US army followed, which entailed losing his Dutch nationality, and which, as a result, made him stateless as he never took US citizenship.

At the height of Elvis’s career, it was often wondered why his manager never visited him when he was serving with the US army in Germany, nor why the singer never toured the UK. Both would have been impossible because Parker never had a passport.

For 30 years Parker worked in the touring carnivals in the small Southern towns of the US, before moving into music management with country stars Eddy Arnold and Hank Snow. Then, one day in 1955, he saw an unknown young man of 20 performing in Louisiana and he saw his future.

However, it took a while and much crafty schmoozing of the boy’s parents. But within a year Elvis was on national television. A year after that he was the most famous young man in the world.

The Colonel And The King by Peter Guralnick

When I had breakfast with Parker in Las Vegas in 1968 (he said: ‘I won’t pick up your tab because I don’t want you to be beholden to me’) I was puzzled by his slight accent. But, as Guralnick explains in this examination of Parker’s relationship with Elvis, the Colonel went to great lengths to hide his past, to the point of never seeing his mother again.

What the Colonel did do, however, was to save copies of every contract and every letter he ever wrote, and which were written to him, which for Guralnick, an excellent Elvis historian, was a treasure trove for this book.

At a quarter of a million words it’s certainly thorough, revealing a man who worked single-mindedly for his client to the point of telling Hollywood producers and record company executives how to do their jobs.

To Guralnick this would suggest that the Colonel was a good manager. I would disagree. To me the Colonel comes across as a brilliant promoter, especially in the early days of Elvis’s success, but hopeless when it came to guiding an intelligent path through Hollywood.

For Parker it was always about million-dollar deals. At no point, in all the letters, do we see evidence of a more thoughtful ambition. Just the opposite.

While Parker never interfered with what Elvis sang, he also never read any of the film scripts.

When Elvis came out of the army in 1960 he was probably the most popular star in Hollywood. A succession of cheap movies (e.g. Girl Happy, Harem Holiday, and Paradise, Hawaiian Style) in which usually the only things worse than the dialogue and the plots were the songs, led within a few years to Elvis admitting that he was considered a joke in Hollywood.

‘I wouldn’t be being honest with you if I said I wasn’t ashamed of some of the movies I’ve been in, and some of the songs I had to sing in them,’ he told me during an interview in Las Vegas. ‘I’d like to say they were good, but I can’t. I had to do them. I signed contracts.’

But the contracts were about money alone. As Elvis talked to me, the Colonel listened silently. Can you imagine the agents of Paul Newman or Frank Sinatra signing their clients to movies without ever reading the scripts? It’s unthinkable.

This story doesn’t have a happy ending. The man they called the King died, aged 42, in 1977 when his addiction brought on a heart attack in his Graceland bathroom.

The Colonel’s addiction never left him, though after Elvis’s death he was no longer a high-roller. Feeling hurt that he’d been abandoned when a Memphis court took away his management of everything Elvis, he lived for another 20 years in a modest Las Vegas home.

But, although he still visited the casinos, $25 bets were his limit.

- The Colonel And The King by Peter Guralnick (White Rabbit, £35, 624pp)