By STACY LIBERATORE, U.S. SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY EDITOR

A new analysis of the Shroud of Turin has provided strong scientific evidence that supports the biblical account of Jesus’ burial.

The Bible says Jesus’ body was wrapped only in spices and a 14-foot linen cloth, believed by Christians to bear His image.

However, a 1998 study determined Jesus’ body was washed before burial, contradicting scripture.

Now, Dr Kelly Kearse, an immunologist trained at Johns Hopkins University, reexamined the ‘washing hypothesis’ originally proposed by forensic pathologist Dr Frederick Zugibe.

Dr Kearse tested human blood samples under post-mortem conditions like reduced clotting and increased acidity. Using ultraviolet light and a microscope camera, he studied how blood transfers to cloth in these states.

His findings indicated that the bloodstains on the Shroud came from an unwashed body, matching Jewish burial customs in the Bible that forbid washing the bodies of those who died violently.

These customs hold that all blood lost during trauma remains part of the body and must be buried with it.

A key discovery was that serum halos, clear rings around blood clots, were visible on many wounds on the Shroud.

These halos only form if blood began to clot before touching the cloth, proving the blood came directly from fresh, unwashed wounds.

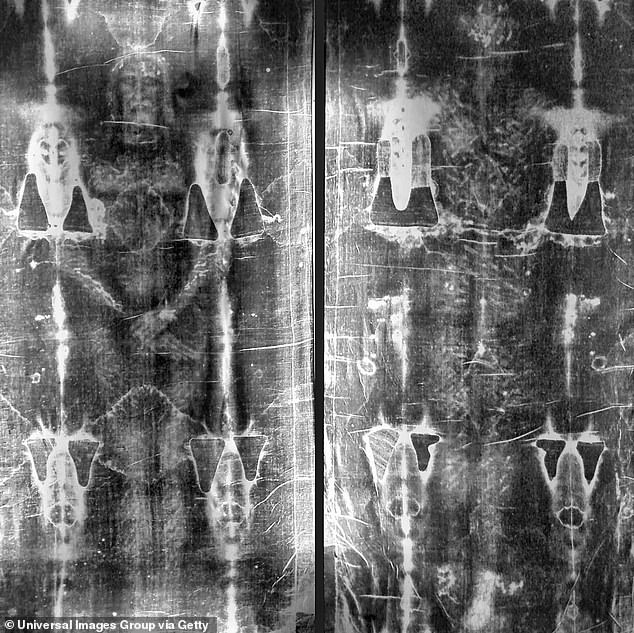

The Shroud of Turin is a piece of linen, measuring 14ft 5in by 3ft 7in, that bears a faint image of the front and back of a man. A new study identified clues within the cloth that supports the Bible

A key discovery was the presence of serum halos, clear rings around blood clots, on many wounds of the Shroud, which only form if blood began clotting before contact with the cloth, proving it came from fresh, unwashed wounds

Dr Zugibe conducted his research based on a passage from The Lost Gospel According to Peter, also known as the Gospel of Peter, an early Christian text that is not part of the canonical Bible.

It is considered an apocryphal or non-canonical gospel and is often classified among the New Testament apocrypha.

‘And he took the Lord and washed him, and rolled him in a linen cloth, and brought him to his own tomb, which was called the Garden of Joseph,’ The Lost Gospel According to Peter 6:8 reads.

Using that text, Dr Zugibe argued that an unwashed, crucified body would be so saturated with blood that it would produce large, indistinct smudges on cloth.

His study used accident victims and found that their wounds produced no clear impressions, even after rinsing.

However, Dr Kearse pointed out that the Shroud shows well-defined stains and serum halos, a key detail that makes the washing hypothesis incompatible with observable evidence.

Recent research has determined that as blood begins to clot, it forms a small blister of plasma, the clear component of blood.

As drying continues, the serum migrates to the outer edges, forming a serum halo that becomes visible under ultraviolet light.

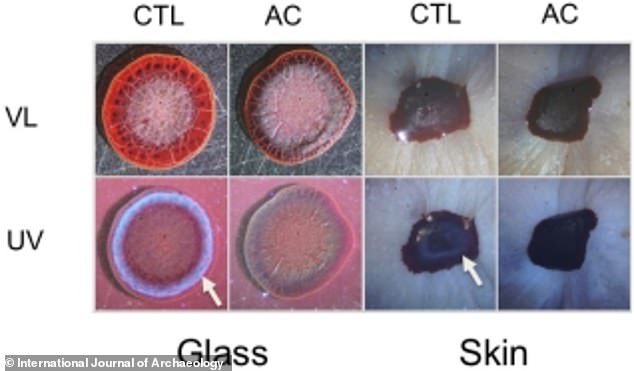

Control (CTL) and anticoagulant (AC)-treated blood samples were dried on glass and skin, then examined under visible (VL) and ultraviolet (UV) light; the white arrow points to the serum halo, which appears only when blood clots naturally, mirroring the patterns seen on the Shroud.

In deceased individuals, blood does not clot properly, and its pH level drops, becoming more acidic.

To simulate these post-mortem conditions in the lab, Dr Kearse adjusted blood samples to match the acidity found several hours after death, then allowed them to dry on skin.

Under these conditions, low pH and poor clotting, serum halos did not form.

However, when blood had a low pH but was allowed to clot naturally, the halos reappeared.

This suggested the presence of serum halos on the Shroud supports the idea that the blood came from clotted, unwashed wounds rather than from blood oozing after washing.

Ultimately, Dr Kearse concluded that no known process could produce the Shroud’s precise blood patterns from a cleaned corpse.

He also theorized that if the body had not been washed, the blood could have transferred to the Shroud in a few ways.

One possibility is that thick, semi-liquid clots of fresh blood stuck to the cloth while still soft.

Another is that dried blood on the body became rehydrated in the damp conditions of a cave tomb, allowing it to adhere to the linen.

Some researchers have proposed that radiation pressure, possibly linked to the moment of Jesus’ resurrection, could have caused the transfer of dried blood to the cloth.

The study pointed out that the Shroud shows well-defined stains and serum halos, a key detail that makes the washing hypothesis incompatible with observable evidence

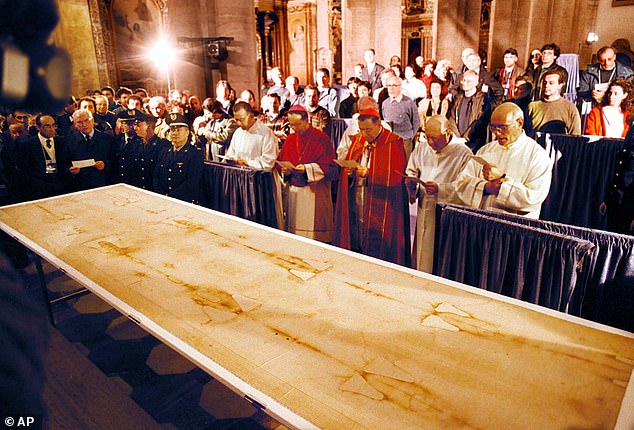

The shroud first appeared in 1354 in France. After initially denouncing it as a fake, the Catholic church has now embraced the shroud as genuine. Pictured, the burial cloth was on display in 1998 in the Cathedral of Turin for the first time in 20 years

However, there is currently no scientific evidence to support this mechanism producing the stain patterns seen on the Shroud.

Dr Kearse’s findings do not prove the Shroud’s authenticity but offer strong support for the biblical narrative of Jesus’ burial.

When first exhibited in the 1350s, the Shroud was touted as the actual burial cloth used to wrap the mutilated body of Christ following his crucifixion.

Also known as the Holy Shroud, the linen bears a faint, full-body image of a bearded man, which many Christians believe to be a miraculous imprint of Jesus.

However, radiocarbon dating performed in the 1980s placed the Shroud’s origin in the Middle Ages, hundreds of years after Christ.