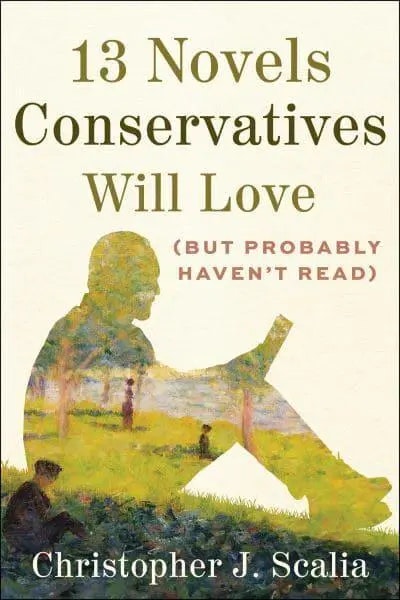

The Victorian Conservative Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, said, “When I want to read a novel, I write one,” and he did just that, writing 16 novels in all. Christopher Scalia, a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a former academic who specialised in 18th-century and early 19th-century British literature, would like conservatives to read more novels and read more widely. Perhaps we might even be inspired to write a novel ourselves after reading 13 Novels Conservatives Will Love (but Probably Haven’t Read)? Or at the very least, read a handful of the novels that Scalia recommends to us.

Why should we concern ourselves with novels? Sir Roger Scruton, whose work is cited often in Scalia’s book, wrote in Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition that conservatism “in its most recent attempt to define itself…has become the champion of Western civilisation against its enemies.” Scalia believes that the novel “is one of the greatest achievements of Western culture”. If we accept these premises, we should conclude that reading novels is an important activity for conservatives. After all, many conservatives in the Anglo-American conservative tradition have turned their hand to this form of art — admittedly with mixed results — such as Sir Winston Churchill, Boris Johnson, and William F. Buckley. Conservatives of the past, or some of them, understood the power of fiction. The American conservative, Russell Kirk, expressed this insight by using Sir Walter Scott as an example. Kirk wrote that “Sir Walter succeeded in popularizing the proud and subtle doctrines of Burke”. Indeed, the Waverley novels, which are covered by Scalia in his book, “carried Burke’s ideas” to a much wider audience because fiction has a greater market than non-fiction works, such as political pamphlets.

Scalia hopes that this book “refreshes how conservatives talk about fiction” and that it will help to restock the “conservative bookshelves”. Additionally, Scalia hopes to assist conservatives “better understand certain foundational ideas and precepts” of their tradition as Kirk’s The Portable Conservative Reader did for him. These are noble aims. Reading this brought to my mind an essay. This was Walter Bagehot’s essay in The Saturday Review, published in April 1856, called Intellectual Conservatism. In which Bagehot categorised conservatives into three types: (1) conservatives of enjoyment; (2) conservatives of fear; and (3) conservatives of reflection. Bagehot writes, which could have been written today, that “it yet can hardly be said that we possess a Conservatism of reflection — at least we do not possess it in the degree which we should” and have “real mastery of the reasons” in favour of conservatism or “a real familiarity with the moral grounds” of this tradition. Scalia seems to hope that more conservatives will possess the tools to become conservatives of reflection — sentiment that I deeply share.

I started reading 13 Novels Conservatives Will Love, whilst I was a Visiting Researcher at the Russell Kirk Center in Mecosta, Michigan, as the book was published two months or so earlier in the United States than here in dear old Blighty. I was sitting in the Califia cabin, in the London Room, surrounded by great books, and in the picture frame on the desk was a quote from Dr. Johnson, which read: “Sir, when man is tired of London, he is tired of life.” I was reading Scalia’s first chapter, which is on Samual Johnson’s book Rasselas.

Perhaps because I was at the Kirk Center, reading Scalia’s book reminded me of Kirk’s Humane Literature for Young Readers, but with a key difference. The difference is that Kirk’s recommendations were for children aged between seven to twelve, and Scalia’s book is aimed at adults. Still, Kirk and Scalia recommend some of the same authors, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walter Scott, and Willa Cather. Another thing you will find in common is that both Kirk’s and Scalia’s suggestions are mostly books by British writers.

With any books or essays that make recommendations, the reader will always think, “why did they not add so and so?” Thus, a list of books can become endless. As Kirk expressed it, “this critic’s problem is not paucity, but plenitude”. The same problem, it seems, was for Scalia. He has somewhat surmounted this problem by suggesting 36 novels in the appendix of the book, bringing the total up to 49. I was so pleased to see P.G. Wodehouse suggested, even if it was in the appendix.

A core strength of the book is that it is affirmative. It displays conservative thought as a rich intellectual and cultural tradition — a source of truth and insight through fiction, such as when it comes to understanding human nature (Rasselas), manners (Evelina), national identity (Daniel Deronda), and fertility (The Children of Men).

Conservatives … will love this book

One criticism of the book, perhaps, could be that Scalia has jumped one step ahead in the process of endeavouring to ensure that conservatives read more novels by recommending more obscure works or writers rather than the mainstay of the conservative fictional canon. Michael Oakeshott’s famous On Being Conservative is useful here, as Oakeshott writes that “To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried.” Starting the newly initiated conservative reader of fiction off on a more well-trodden, familiar, and tried-and-tested path may be easier if the person is more familiar with the canon. (Of course, that would not make that book as interesting to read.)

Conservatives, both the initiated and uninitiated into the canon, will love this book. As C.S. Lewis wrote to Arthur Greeves, “I can’t imagine a man really enjoying a book and reading it only once.” This is my view of Scalia’s book; you will be dipping back into it regularly. The reason why is that Scalia has not just managed to show that conservative thought is a living and tender thing, but that it is fun and imaginative too.